Australian Odyssey

Published in Ecology & Evolution

"The ancestor of the Rivatjingu people was named Djankawu, and he came over the sea from Baralku in a canoe. He was accompanied by his two sisters, and they followed the morning star to land in north-eastern Arnhem Land" - Flood.J, Archaeology of the Dreamtime, Collins Australia (1989).

I’m fascinated by the story of how humans reached Sahul, the continental mass that united Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea until the end of the Pleistocene. It’s a swashbuckling tale of long sea crossings, dangerous oceanic currents, and ridiculously low odds of survival. Like the best swashbuckling tales, there’s also a certain degree of conjecture involved – there is no surviving archaeological evidence of Pleistocene maritime technology, and even 19th Century Aboriginal boats would not have been capable of undertaking the 100km journey stages required to island hop from Sundaland (mainland southeast Asia, not to be confused with Sunderland…) to Sahul. Somewhere, at sometime after humans reached Australia, the technology was lost.

Timing is another interesting question – for a long time one of the mysterious parts of the puzzle was that humans suddenly appear too far south. Assuming the route in to Australia itself was from the north (as suggested by the Dreaming myth quoted above), it really puzzled archaeologists that some of the earliest evidence of human presence were the spectacular, ochre-covered burials at Lake Mungo in New South Wales dating to 40,000 years ago. Such evidence, so far south, led to interpretations of either coastal or water-corridor dispersal routes to explain how quickly humans had reached this part of the world – until about ten years ago the Out of Africa dispersal of modern humans was thought to have happened 60,000 years ago. Archaeologists were more or less sure that humans had avoided the Central Arid Zone as uninhabitable until much more recently, perhaps until they were forced to intensify foraging practices (using grindstones and other processing technology, for example, to extract more food out of available resources) in the terminal Pleistocene.

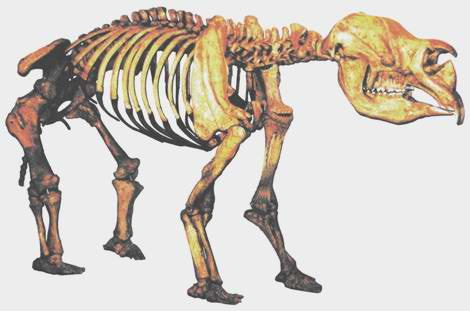

Earlier this year, a widescale population genetics study of Aboriginal Australians suggested a divergence from modern Eurasians 72-51,000 years ago, and now Hamm et al report in Nature that settlement of the arid interior was far earlier than previously thought, about 49,000 years ago. Warratyi rock shelter preserves reliably dated, stratified evidence of extinct Australian megafauna, including the giant wombat, Diprotodon, as well as the earliest evidence in Australia or southeast Asia for, respectively, ochre, gypsum pigment, bone tools, hafted tools, and backed [stone tools blunted on one side, probably for comfort in use] artefacts. To say that these findings are revolutionary is an understatement: for years, the Pleistocene Australian stone tool record had been dismissed as homogenous, crude, and lumpy. Although Aboriginal cultural traditions were indicative of great complexity and great antiquity (as evidenced by the Lake Mungo burials, for example) the contrast with the stone tools, the bread and butter of archaeologists seeking to understand the past, was immense.

Dippy: murdered by humans? Photo taken by Erich Schulz ([1]) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In context then, most of the Warratyi findings shouldn’t be surprising: it’s more a case of putting [interpretations of] the Australian archaeological record to rights, albeit through spectacular finds confirming the rapid dispersal of humans throughout all corners of Australia. The association of humans with megafauna is, perhaps, more surprising – a human role in Australian Pleistocene megafaunal extinction has previously been disputed, but this find confirms humans were at least partially responsible. It's worth noting the technological innovations that have allowed the establishment of these finds, too: Optically Stimulated Luminescence dating can break the Radiocarbon "barrier" of approximately 50,000 years before present (or rather, before 1950...), yet still deliver finely resolved chronologies; use-wear and residue analysis combining biochemical staining techniques, high-power and portable microscopy inform on pigments and hafting residues. Much of this technology is being pioneered in Australia - fingers crossed that the techniques deliver more groundbreaking findings like those from Warratyi in the future.

Hamm, G. et al Cultural innovation and megafauna interaction in the early settlement of arid Australia, Nature (2016) doi:10.1038/nature20125

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in