Fairness preferences in young children vary depending on the gender composition of the group

Published in Behavioural Sciences & Psychology and Economics

The following scenarios are fictional, but every parent with children of kindergarten or school age know that they do take place like this, or in similar form, every day. Imagine you want to buy some ice cream with your 7-year-old son Lucas. After negotiating how much ice cream he would be allowed to order, Lucas starts complaining loudly about how unfair it is that he can only order one scoop, while his best friend Henry always gets two. But then his school mate Leo happens to pass by. Leo has no ice cream at all and asks Lucas if he may have a bite, but Lucas refuses to share with him. Lisa, by contrast, a friend of theirs who happens to be at the ice cream café, too, feels sorry for Leo and offers him some of her own ice cream portion.

So far, so stereotypical: boys are very quick to detect that they are disadvantaged relative to their peer, but they are not ready to share with others who have less. Girls, by contrast, seem to be much happier to share with their disadvantaged friends.

But then, the next day, something happens that does not fit this gender stereotype: Lucas brings chocolate to school which he happily shares with Lisa, who has none. How can we make sense of this? Is Lucas just inconsistent in his (un)willingness to share chocolate or ice cream, or is something else happening?

These fictional scenarios illustrate the observation that children develop a sense of (un)fairness relatively early on, in particular, when they feel that they are worse off than other children. But, as these stories also exemplify, sometimes, children are also sensitive to another kind of inequality – the unfairness when someone else is worse off than them – and they act upon it, for example, by sharing their resources with those who have less. And these stories also seem to suggest that girls would be more sensitive to this latter kind of inequality than boys.

The dislike of being worse off than others is called ‘disadvantageous inequity aversion’, the dislike of others being worse off than oneself is called ‘advantageous inequity aversion’ (Fehr and Schmidt, 1999). It is widely recognized that both forms of inequity aversion develop during childhood, with disadvantageous inequity aversion emerging earlier than advantageous inequity aversion (Benenson et al., 2007; Fehr et al., 2008; Blake and McAuliffe, 2011; Blake et al., 2015). And it is also relatively well-known that girls are generally more (and earlier) ready than boys to share their resources with those who have less (Harbaugh et al., 2003; Gummerum et al., 2010; Fehr et al., 2013) – a trend that is often believed to continue into adulthood; just think of the gender stereotype that women are more compassionate and men are more competitive.

In our Communications Psychology paper (van Wingerden et al., 2024), we aimed to better understand the developmental trajectory of gendered advantageous and disadvantageous inequity aversion. Specifically, we sought to determine whether children’s attitudes toward unequal reward distributions – whether advantageous or disadvantageous – depend solely on their own gender, or if their fairness preferences are also influenced by the gender of the other child on the receiving end of the reward distribution. In simple words: are boys really more envious of others who are better off, and girls more compassionate with those who are worse off, or does their fairness attitude change with the gender of the person they are dealing with?

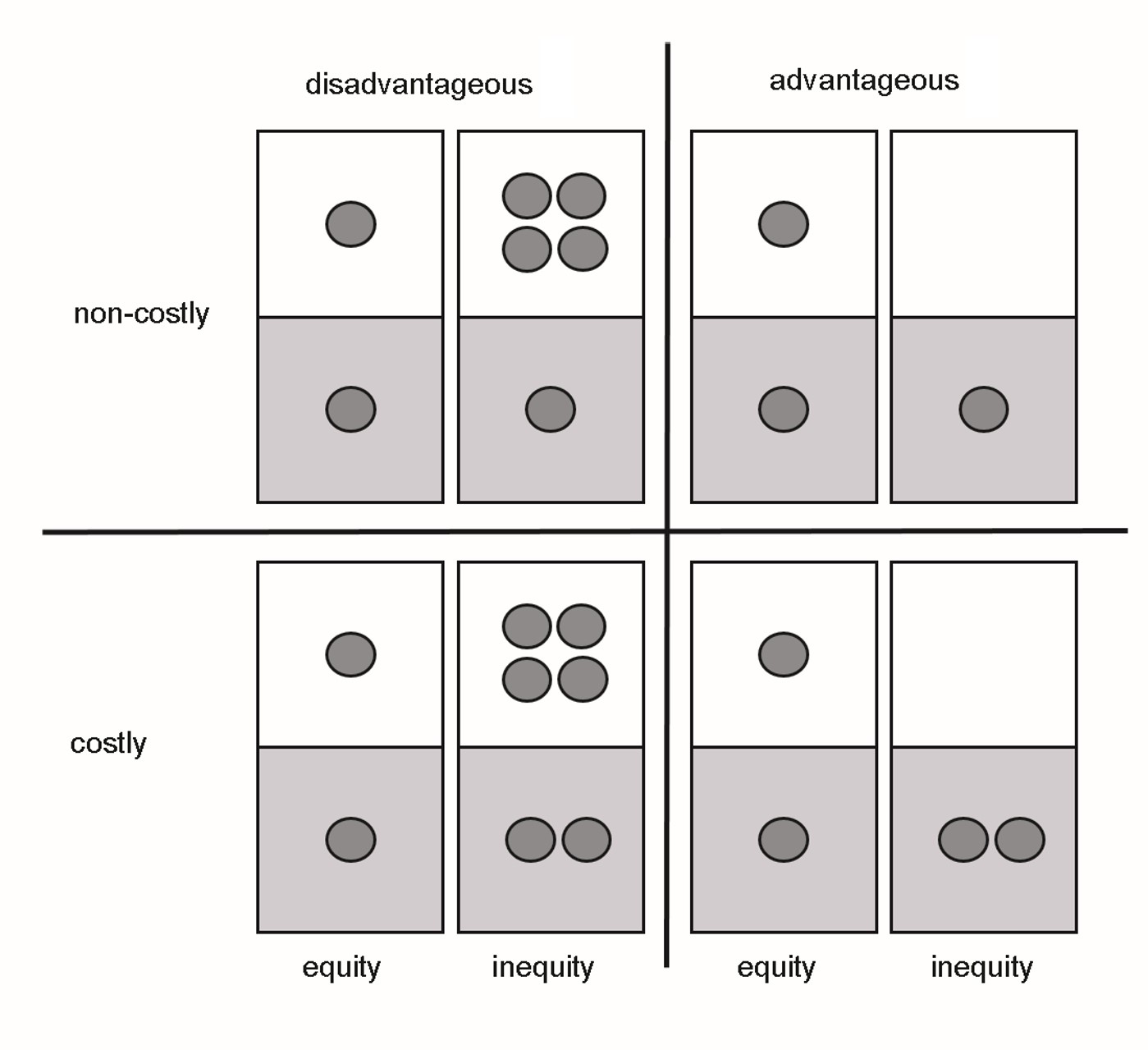

To examine this, we tested three- to eight-year-old children in a paired resource allocation task. In this task, an allocator child had to make decisions between equal and unequal distributions of rewards (smiley stickers) between themselves and another child, the recipient (figure 1). We manipulated if the recipient was better off (disadvantageous inequity) or worse off (advantageous inequity) than the allocator, and if the choice of the equal sticker distribution was costly or not (in the costly scenario, allocators would receive one sticker less if they chose the equal distribution). We also manipulated the genders of the allocators and the recipients and, thus, created all dyadic gender combinations: boy-boy, boy-girl, girl-boy and girl-girl.

We indeed found gender-related effects: girls more than boys aimed to reduce advantageous inequity, suggesting that they were more sensitive to unfairness in their favor; in other words, girls were really more compassionate than boys. Importantly, however, we also found that the gender of the recipient mattered for the allocators’ fairness preferences: allocators of both genders revealed stronger disadvantageous inequity aversion when the better-off recipient was male than when she was female, suggesting generally higher levels of envy when the recipient was a boy. Notably, older girls exhibited an envy bias, i.e., they tolerated disadvantageous inequity more when the resource allocation was in favor of other girls than when it favored boys. We also observed a gender-related spite gap in boys: boys were strongly egocentric when the recipient was a boy, too, but not when she was a girl, i.e., boys selfishly maximized their own sticker payoff and accepted that the other boy would go away empty-handed.

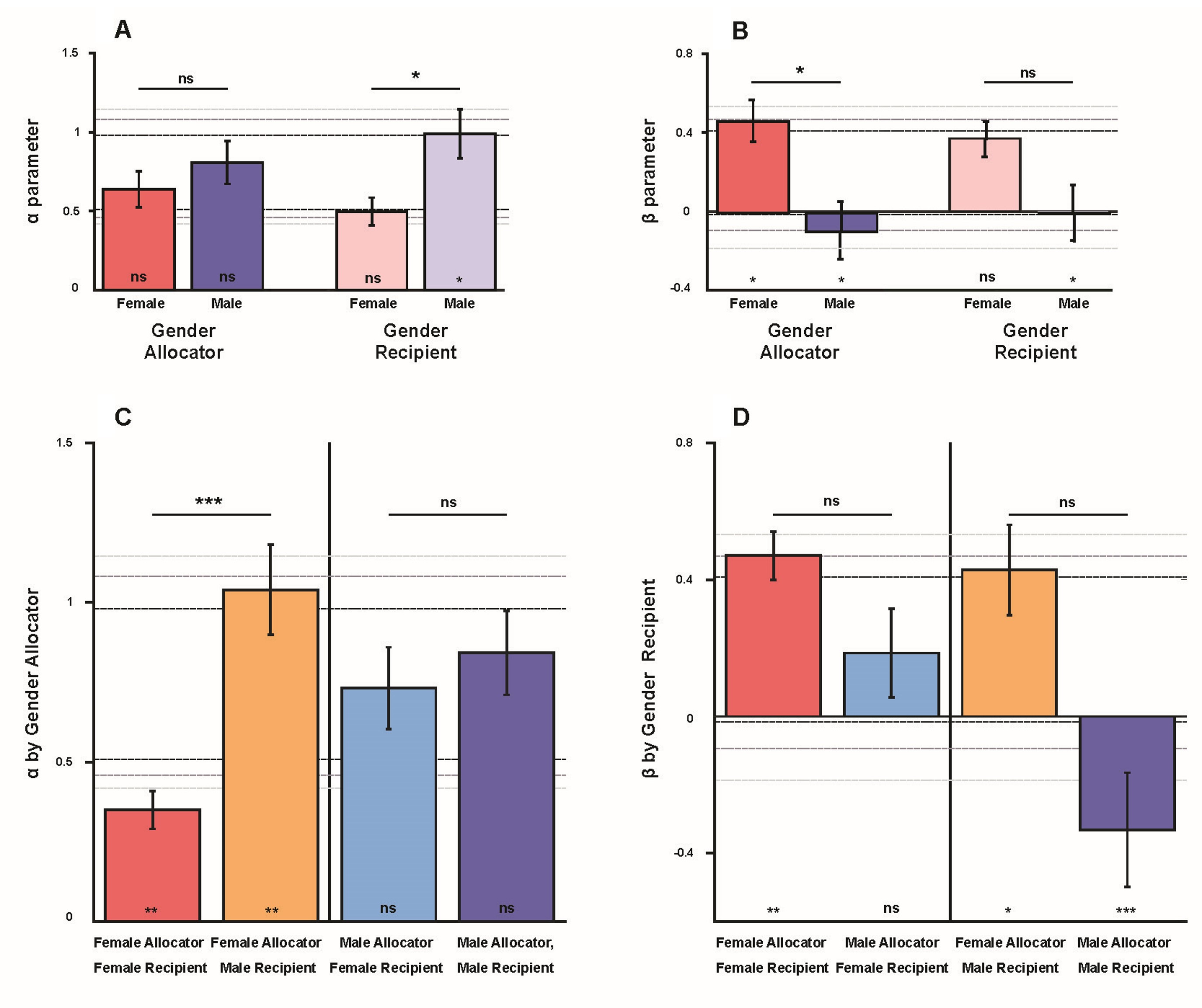

To corroborate these results, we fitted a prominent quantitative model of fairness preferences, the Fehr-Schmidt model of inequity aversion (Fehr and Schmidt, 1999), to our data. This model yields two parameters, a and b, which quantify the individual sensitivity to disadvantageous (a, often interpreted as a metric of envy), or advantageous inequity aversion (b, often interpreted as compassion), respectively. We found that both parameters indeed depended on the genders of the allocators, but, importantly, also on the genders of the recipients, and they were different in the different gender-dyad configurations (figure 2). Particularly, a (envy) was higher when the recipient was a boy, compared to a girl, but not necessarily when the allocator was a boy (figure 2A and 2C), suggesting that boys are not always envious by nature, although they are generally treated with more envy. b (compassion) was higher in female allocators, independent of the gender of the recipient (figures 2B and 2D), revealing unconditional compassion in girls. Female recipients were also treated with higher compassion by allocators of both genders, including boys (figure 2B and 2D). By contrast, as mentioned above, male allocators revealed spiteful preferences, i.e., negative b, when the recipient was male, too, but not when she was female (figure 2D), substantiating the conclusion that boys attached positive value to other boys being worse off.

In summary, our results suggest that children’s fairness attitudes do indeed depend on gender, but notably, not only on their own genders, but also on those of the other children they are interacting with. While our data are in line with some common gender stereotypes, e.g., regarding female compassion and male competitiveness, our findings also suggest that the story is a bit more complicated, e.g., regarding male envy (boys are treated with more envy than girls, but are not necessarily more envious by nature). This pattern hints at contextualized gender-related social preferences that evolve with age and depend on same and cross-gender interaction experiences.

Gender stereotypes permeate today’s society. Our study highlights the pervasiveness of gendered differences in social behavior, even in young children, possibly contributing to cultural gender typecasts in adult life. However, as our study also shows, at least in the field of fairness preferences, gendered differences solidify over an extended period. This observation also leaves room for promoting non-gender-stereotyped fairness attitudes during this critical period.

References

Benenson JF, Pascoe J, Radmore N (2007) Children's altruistic behavior in the dictator game. Evol Hum Behav 28:168-175.

Blake PR, McAuliffe K (2011) "I had so much it didn't seem fair": Eight-year-olds reject two forms of inequity. Cognition 120:215-224.

Blake PR, McAuliffe K, Corbit J, Callaghan TC, Barry O, Bowie A, Kleutsch L, Kramer KL, Ross E, Vongsachang H, Wrangham R, Warneken F (2015) The ontogeny of fairness in seven societies. Nature 528:258-261.

Fehr E, Schmidt KM (1999) A theory of fairness, competition and cooperation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 114:817-868.

Fehr E, Bernhard H, Rockenbach B (2008) Egalitarianism in young children. Nature 454:1079-1083.

Fehr E, Glätzle-Rützler D, Sutter M (2013) The development of egalitarianism, altruism, spite and parochialism in childhood and adolescence. European Economic Review 64:369-383.

Gummerum M, Hanoch Y, Keller M, Parsons K, Hummel A (2010) Preschoolers' allocations in the dictator game: The role of moral emotions. Journal of Economic Psychology 31:25-34.

Harbaugh WT, Krause K, Liday SG (2003) Bargaining by children. University of Oregon (Working Paper):1-40.

van Wingerden M, Oberließen L, Kalenscher T (2024) Egalitarian preferences in young children depend on the genders of the interacting partners. Commun Psychol 2:89.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Psychology

An open-access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary. The scope of the journal includes all of the psychological sciences.

Ask the Editor – Collective decision-making

Got a question for the editor about Experimental Psychology and Social Psychology? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Intensive Longitudinal Designs in Psychology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Replication and generalization

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Dec 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in