Behind the Paper: Engineering Reliable Metal-Ceramic Joints for High-Performance Industrial Systems

Published in Materials and Mechanical Engineering

In many advanced manufacturing sectors, from aerospace propulsion to automotive powertrains and high-temperature energy systems, engineers face a persistent and fundamental materials challenge: how to reliably join lightweight metals with heat-resistant ceramics in a way that is strong, stable, and durable under real service conditions. Aluminum alloys such as AA6061 are widely favored for their excellent strength to weight ratio, machinability, and corrosion resistance, while ceramics such as alumina and yttria-stabilized zirconia are indispensable for their extreme thermal stability, wear resistance, and chemical inertness. Combining these two materials promises exceptional performance, yet the reality is that metal-ceramic joining is among the most difficult tasks in structural manufacturing because metals deform plastically while ceramics fail in a brittle manner and their thermal expansion behavior is fundamentally mismatched. Traditional fusion welding often leads to cracking, residual stresses, and the formation of brittle interfacial reaction layers that severely compromise structural integrity. This challenge formed the industrial motivation behind my recent study on friction welding of AA6061 aluminum alloy to an alumina-25 wt.% YSZ ceramic composite, where I sought not only to demonstrate joint formation but, more importantly, to understand what truly controls joint reliability at the microscopic and atomic scales.

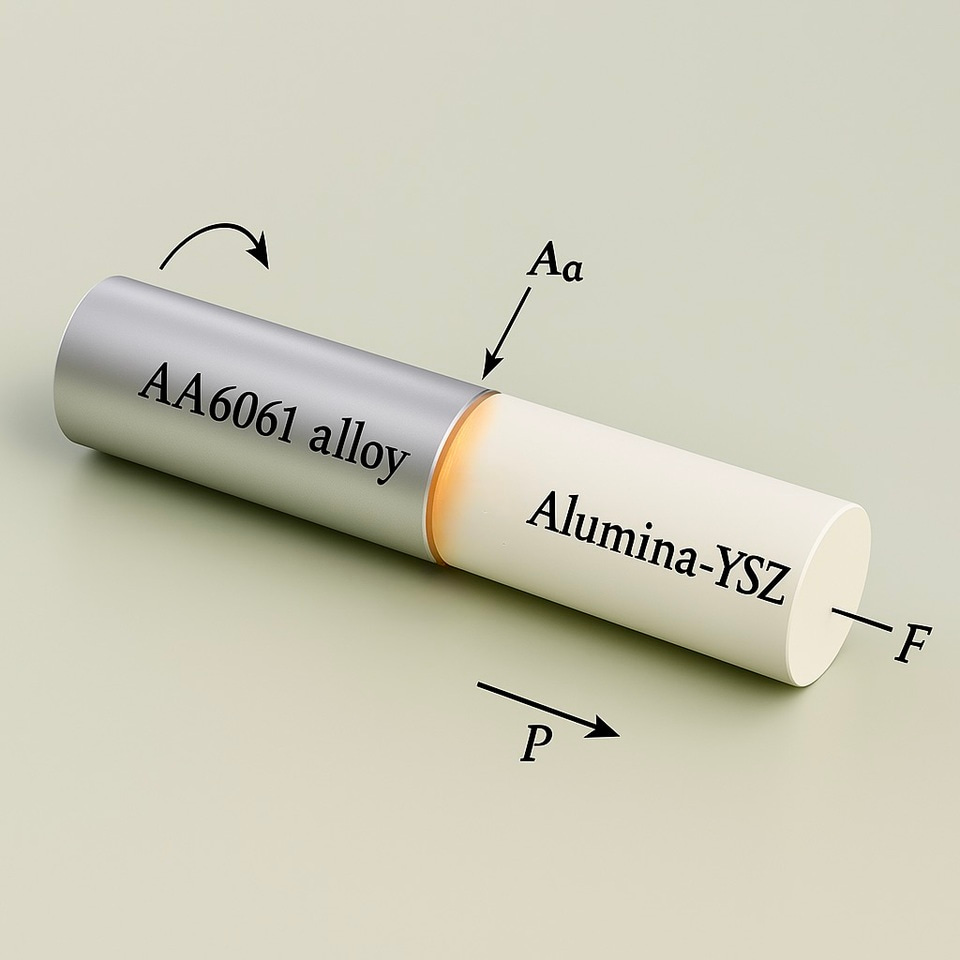

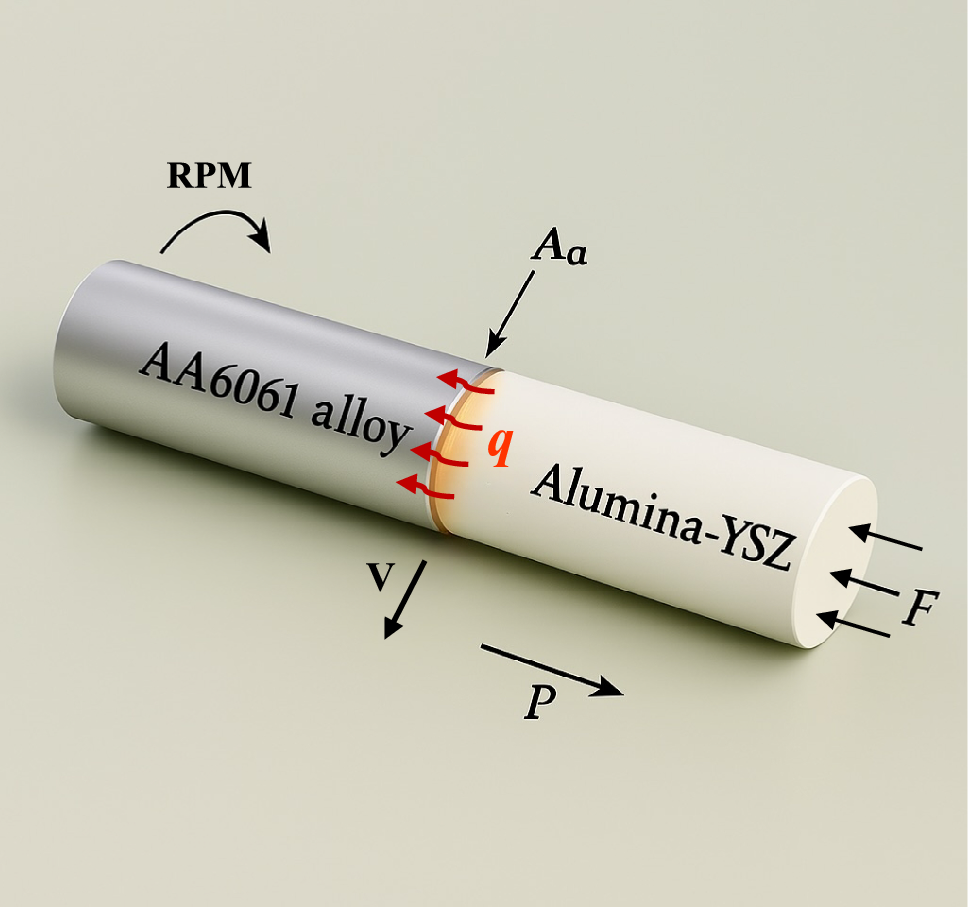

Rather than relying on melting and solidification, I employed rotary friction welding, a solid-state joining process already used in the production of aerospace shafts, automotive driveline components, heavy duty rotating parts, and defense hardware. In this process, heat is generated purely through friction and severe plastic deformation at the interface, followed by forging under axial pressure, which allows metallurgical bonding without the large heat-affected zones typical of fusion welding. In my investigation, I systematically varied the rotational speed from 630 to 2500 rpm while keeping the axial force and friction time constant, allowing me to isolate the influence of thermo-mechanical input on interfacial microstructure and mechanical performance. From an industrial perspective, the most critical question was not whether the joint could be formed, but whether increasing process intensity would consistently improve structural performance or silently introduce failure mechanisms that only appear under service loading. To address this, I combined scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction peak profile analysis, microhardness measurements, and four-point bending tests so that the connection between processing parameters, atomic-scale defect structures, and real joint strength could be clearly established.

One of the most important findings of this work, and one with direct industrial implications, is that increasing process severity does not necessarily translate into more reliable metal-ceramic joints. As rotational speed increased, frictional heat flux rose significantly, resulting in pronounced grain refinement on the aluminum side of the joint due to dynamic recrystallization and a rapid increase in dislocation density. From a classical metallurgical standpoint, this refinement was expected to enhance mechanical strength, and indeed the microhardness of the joint increased with speed. However, when actual structural performance was evaluated using four-point bending tests, a very different trend emerged. The highest joint strength was achieved at the lowest rotational speed of 630 rpm, while joints produced at 1800 and 2500 rpm exhibited a substantial reduction in bending strength and failed predominantly in a brittle manner. Detailed microstructural examination revealed that excessive heat input at higher speeds promoted the formation of thick interfacial reaction layers, localized oxide and intermetallic phases, and high residual tensile stresses arising from thermal mismatch between aluminum and ceramic. These factors overwhelmed the benefits of grain refinement and dislocation hardening, causing early crack initiation and rapid fracture. From an industrial manufacturing perspective, this demonstrates a critical reality that is often overlooked in high-speed production environments: maximizing hardness and microstructural refinement through excessive thermal and mechanical input can be directly detrimental to structural reliability in dissimilar metal-ceramic joints.

At the atomic scale, the role of dislocations proved to be central in understanding this behavior. Dislocations are line defects in the crystal lattice that govern plastic deformation, work hardening, fatigue resistance, and crack initiation. Through advanced X-ray diffraction peak broadening analysis using modified Williamson Hall and Hall-Petch models, we quantified the evolution of dislocation density as a function of welding speed and heat flux. Dislocation density increased from approximately 8.6 × 1015 m-2 at low heat input to nearly 12.7 × 1015 m-2 at the highest speeds, while crystallite size decreased from roughly 90 nm to around 60 nm. These changes confirmed that severe thermo-mechanical loading during friction welding activates intense dynamic recrystallization and dislocation multiplication in AA6061 near the interface. However, the industrial lesson is not merely that dislocation density can be engineered through welding parameters, but that dislocation mediated strengthening must be carefully balanced against interfacial chemistry and thermal stress development. In other words, atomic scale strengthening mechanisms may raise hardness, but they do not guarantee resistance to brittle interfacial failure when ceramic phases are involved. This distinction is essential for engineers designing joints that must survive vibration, thermal cycling, impact loading, or long term service at elevated temperatures.

The broader significance of this study lies in its direct relevance to high performance industrial systems where hybrid metal-ceramic structures are increasingly unavoidable. Applications include thermal barrier components, aerospace structural interfaces, lightweight automotive hybrid parts, rotating energy components, and high-temperature wear systems where both low mass and thermal durability are required. The key engineering takeaway is that friction welding of metal-ceramic combinations can be a highly effective industrial joining route, but only when thermo-mechanical parameters are optimized to suppress brittle interfacial reactions while maintaining sufficient plastic flow and bonding. Myresults clearly demonstrate that moderate processing conditions, rather than extreme ones, produce the most reliable joints, as they minimize oxide formation, reduce residual stresses, and preserve interfacial cohesion. Equally important is the methodological contribution of this work, which shows how physics based microstructural tools such as X-ray dislocation analysis and Hall–Petch strengthening relations can move industrial welding practice beyond trial-and-error parameter selection toward predictive, microstructure-driven process optimization. Instead of relying solely on macroscopic hardness or visual inspection, manufacturers can use these techniques to quantify defect density, grain refinement, and interface stability as part of advanced quality control and process design strategies.

The full paper, “Dislocation Mechanics and Interfacial Grain Refinement in Dissimilar Metal-Ceramic Friction Welds: A Case Study on AA6061/Alumina-25 wt.% YSZ,” is published in the Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance and can be freely viewed via the official Springer SharedIt link . I hope this work contributes not only to the scientific understanding of dissimilar material joining, but also to the practical advancement of industrial manufacturing processes where reliability, safety, and long term performance are non-negotiable requirements. I warmly welcome discussion with engineers, researchers, and industrial practitioners working in welding, surface and interface engineering, lightweight structural design, thermal management, and advanced manufacturing systems, as collaboration between academia and industry is ultimately what transforms microstructural insight into real world engineering solutions.

Follow the Topic

-

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance

This journal publishes research on all aspects of materials selection, design, processing, characterization, and evaluation.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in