Behind the Paper: How the Red Sea dried up and flooded back

Published in Earth & Environment

Today, the Red Sea is a deep, narrow seaway between Africa and Arabia, connected to the Indian Ocean through the Bab el Mandeb Strait. But 6.2 million years ago, it experienced a near-complete desiccation, exposing much of its floor to erosion, before being rapidly refilled by ocean water. Our study reconstructs this event using seismic mapping, well data, micropaleontology, and strontium isotope dating, linking it to regional tectonics and the Messinian Salinity Crisis (MSC).

A boundary in the subsurface

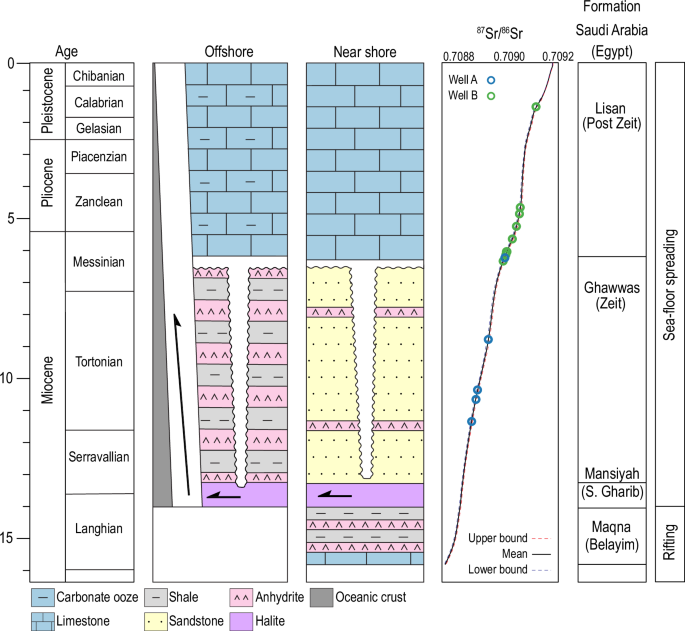

Seismic profiles across the Red Sea reveal a continuous, high-amplitude reflector called S-reflector. It separates thick Miocene evaporites (mainly halite and anhydrite) below from Pliocene-Pleistocene marine sediments above. Its origin has been debated and variously attributed to wave erosion, dissolution, or slow environmental shifts.

To resolve this, we examined more than 100,000 km² of seismic data along the Arabian margin and tied the reflector to direct samples from two offshore wells. Well A, in deep water, provided 30 m of core across the reflector, and Well B, near the margin, offered drill cuttings from key intervals.

A sharp environmental change

In Well A, the section below the S-reflector consists of laminated and massive anhydrite, with halite at greater depth, barren of marine fossils. Above it, fossil-rich limestones contain benthic foraminifera, red algae, and worm tubes, clear indicators of normal marine salinity. Well B shows reef limestones directly overlying Late Miocene anhydrite.

Strontium isotope dating provided the timeline: limestones above the reflector are 6.3-6.2 million years old, while anhydrites below range from ~8.8 to 11.4 Ma. This constrains the erosion event to just before 6.2 Ma, slightly earlier than the peak of the MSC in the Mediterranean.

Seismic evidence for erosion

Seismic profiles confirm the S-reflector is an angular unconformity, an erosion surface cutting into tilted Late Miocene strata.

We see:

- Truncation of minibasin sediments, with up to a kilometre of material removed.

- Flat-topped salt diapirs, likely due to dissolution and erosion of uplifted salt structures.

- Sediment wedges in minibasins, interpreted as reworked material deposited during the event.

- The surface is continuous from the Gulf of Suez to the Hanish Islands, indicating a basinwide process.

Isolation and desiccation

We interpret the unconformity as the result of complete isolation of the Red Sea from the Mediterranean during the early Messinian. Before 6.2 Ma, the northern connection through the Gulf of Suez was restricted, cutting off inflow from the Tethys. Without any inflow from the Gulf of Aden, the arid climate drove hypersaline conditions to the extreme, leading to basin desiccation.

Subaerial erosion, wind deflation, and dissolution of exposed salt flattened the basin floor. Sediment was redeposited in adjacent subsiding areas, while salt diapirs were truncated. This landscape persisted for only a short time, likely less than 100,000 years, before marine conditions returned.

A flood from the south

The return of marine fauna and normal salinity at 6.2 Ma required a new water source. Faunal evidence shows a shift to Indian Ocean species, indicating that reflooding came from the south. Bathymetric data reveal a 320 km long submarine canyon linking the Gulf of Aden to the southern Red Sea, cutting through the volcanic Hanish sill, the shallowest barrier between the two basins.

We propose that a catastrophic flood from the Indian Ocean carved this canyon and refilled the Red Sea and Gulf of Suez. This event preceded the well known Zanclean flood that refilled the Mediterranean by nearly a million years.

Lasting consequences

The 6.2 Ma reflooding permanently shifted the Red Sea’s oceanographic connections:

- Final break from the Mediterranean and after this, its marine life aligned with the Indian Ocean realm.

- First full southern gateway, establishing the circulation pattern that persists today.

This event also highlights that restricted basins can undergo rapid, extreme environmental change.

Methods

This work relied on integrating geophysical, geological, and geochemical data:

- Seismic mapping traced the unconformity across the basin and documented truncation patterns.

- Core and cuttings analysis reconstructed depositional environments across the S-reflector.

- Strontium isotope dating provided precise ages.

Looking ahead

The southern gateway remains an underexplored link in this story. Detailed mapping and sampling of the submarine canyon and Hanish sill could confirm flood-related incision and refine estimates of the refilling rate.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in