Behind the paper: Tracing a heart disease mutation to the kidney

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology and Biomedical Research

When I first encountered the clinical data showing that children born with congenital heart disease (CHD) almost invariably develop kidney problems early in life, which often persist through adulthood, I couldn’t stop thinking about a seemingly simple question: Is the heart really the primary target organ — or is there a deeper, shared genetic story unfolding much earlier in development but clinically missed due to the lack of appropriate diagnostic tools?

Our new paper1 published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, “Engineered human induced pluripotent stem cell models reveal altered podocytogenesis in congenital heart disease-associated SMAD2 mutations,” is the result of that question and of a long, collaborative journey that began years before opening my research lab and the first experiment in this study.

How the project began: a shared gene and a mutual promise

The seeds of this work were planted during my postdoctoral years at Harvard University, where I met Tarsha Ward. We were both awardees of the Harvard Medical School Dean’s Postdoctoral Fellowship. Tarsha and I were incredibly energized by the possibilities of stem cell biology, gene editing, and human disease modeling. Tarsha was a fellow in the Seidman laboratories, where she focused on the genetics of congenital heart disease. I was a fellow at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, working in the laboratories of Donald Ingber and George Church. I later established my independent research lab at Duke University, where my team specializes in stem cell differentiation and microphysiological systems (including organs-on-chips and organoids) and their applications in uncovering the mysteries of tissue development and disease.

In our early conversations over lunches and pre- and post-seminar chatter, we imagined a future in which we could use human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to connect genetic variants directly to organ-level disease—without relying solely on animal models that often fail to capture human-specific biology. We agreed that one day, we would work on this idea together. Tarsha had shared her growing interest in SMAD2, a gene emerging from her work and related CHD genomic studies as a recurrent player in patients with severe cardiac phenotypes. At the same time, I was becoming increasingly fascinated by the genetic basis of cardio-renal disease and how genes, including SMAD2, are central regulators of early cell fate decisions and organ development, with potential impact far beyond the heart. That convergence—her experience in the genetics of CHD, my experience in stem cell differentiation and microphysiological systems as models of human development and disease, and our shared interest in multiorgan disease and CHD-associated genes in development and kidney biology—became the catalyst for this study.

The developmental puzzle: one gene, many organs

In my Nature Reviews Genetics research highlight2 on SMAD2, I reflected on an earlier work from the Seidmans’ Labs led by Tarsha, and how genomic sequencing has uncovered numerous rare and de novo variants associated with CHD and related disorders3, but left us with a significant knowledge gap: understanding how these variants influence cell identity (e.g., molecular expression and lineage specification) and behavior (e.g., tissue formation, patterning, function, and disease progression). SMAD2 is particularly intriguing because it operates at the intersection of pluripotency, embryonic germ-layer patterning, organ formation, and organismal survival.

In the early stages of development, SMAD2 interacts with transcription factors, including NANOG, TEAD3/4, and OCT4, to regulate cell lineage commitment and differentiation. The molecular machinery that helps shape the heart also forms the kidney, many other organs, and the vascular system. In traditional experimental model organisms such as mice, complete loss of SMAD2 expression is embryonically lethal, making it challenging to study later organ-level consequences of gene modifications in vivo. Human iPSC models, coupled with genome editing strategies and multicellular models (e.g., organoids and microfluidic organs-on-chips), offer a unique way to bridge that gap.

At the same time, clinical observations were painting a consistent and troubling picture: children and adults with CHD, including those with SMAD2 variants, often developed progressive kidney dysfunction characterized by proteinuria, glomerulosclerosis, fibrosis, etc. Yet, it remained unclear whether these kidney complications were purely secondary to hemodynamic stress and reparative surgical procedures for the heart, or whether the same mutation that altered heart development was independently reshaping the kidney from developmental stages to organ-level function.

Engineering a human microphysiological model of a multi-organ disease

This was the central question our study set out to answer: Can a CHD-associated SMAD2 mutation, by itself, derail kidney development and function?

To address this question, we combined complementary strengths across our research laboratories, institutions, and biomedical fields: In the Seidmans group, Tarsha led the CRISPR-Cas9-based genome engineering of isogenic human iPSC lines carrying loss-of-function SMAD2 variants identified in patients with CHD. These isogenic cell lines closely mirror the human genetic context.

In my research group, we examined what happened when SMAD2 was dysfunctional in human developmental continuum. With assistance from other members of my lab, graduate student Rohan Bhattacharya performed the experiments using the wild-type and mutant iPSCs to trace cellular development in a step-by-step manner:

- from pluripotent stem cells through early mesoderm and intermediate mesoderm,

- into specialized kidney cell types, particularly podocytes,

- into vascular endothelial cells capable of forming the specialized fenestrated structures of a functional kidney glomerulus,

- and finally, into a microengineered glomerulus-on-a-chip model that recapitulates the kidney’s blood filtration or selective molecular sieving function.

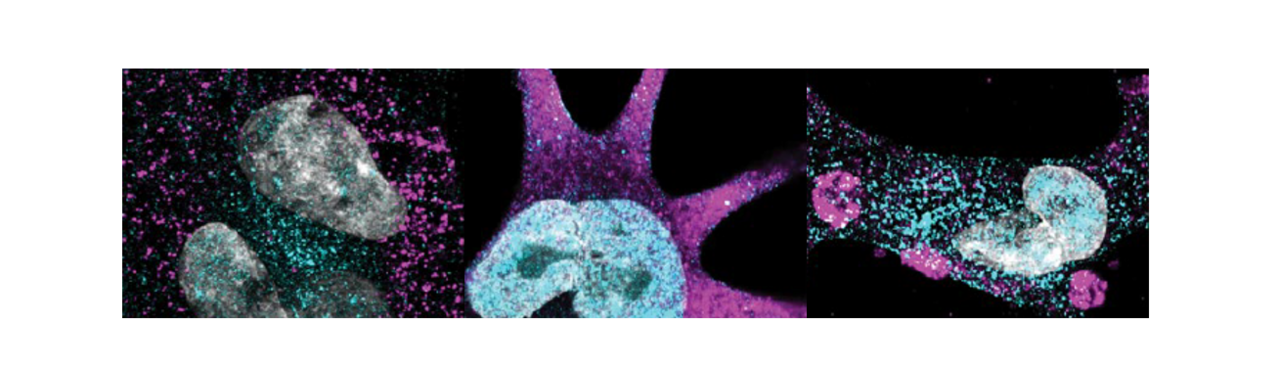

What we found was striking. Loss-of-function SMAD2 variants shifted mesoderm patterning away from the medial mesoderm fates that normally give rise to kidney structures and toward alternative trajectories. Precursors to kidney cell types exhibited altered gene expression, abnormal epithelial–mesenchymal dynamics, and disrupted lineage specification. Downstream, the podocytes derived from these mutant intermediate mesoderm cells failed to mature properly. Instead of forming the complex arborized foot processes and interdigitations that create the kidney’s filtration barrier, they displayed effacement-like phenotypes and impaired cytoskeletal organization. When we integrated these cells into a glomerulus-on-a-chip, the engineered filtration barrier leaked albumin—recapitulating the proteinuria observed in patients with clinically confirmed CHD and kidney disease.

In other words, the SMAD2 mutations associated with CHD were sufficient to disrupt kidney development and filtration function in a human-relevant model, even without direct interconnection to heart tissue or organ systems.

A shift in how we think about congenital heart disease

Our findings echoed decades of clinical work documenting that more than a quarter of children with CHD develop extracardiac complications, and that kidney dysfunction is both common and tightly linked to mortality risk. What our work adds is mechanistic and human-relevant experimental evidence that:

- A single genetic driver, a pathogenic SMAD2 variant, can simultaneously shape heart and kidney development.

- Kidney injury in CHD can begin very early, at the level of mesoderm patterning and nephron lineage determination, long before overt clinical signs emerge.

- Podocyte defects and aberrant glomerular filtration barrier function are not necessarily secondary targets of hemodynamic stress; they can be primary manifestations of the underlying developmental consequences of the genetic mutations.

For me, as a stem cell biologist and bioengineer, this reinforces a broader principle I argued in the Nature Reviews Genetics piece: to faithfully connect genotype to phenotype, we must embrace model systems that span early development to postnatal tissues and organ physiology and enable parallel or simultaneous investigation of multiple organs. Accomplishing this goal in a human-relevant context, as we did in this study, is critical to translating fundamental discoveries into clinically practical strategies to improve patients' lives.

From discovery to care: why this matters for patients

Our hope is for these findings to catalyze earlier and routine kidney monitoring and more personalized care for patients with CHD, especially children. The reasons are clear:

- Kidney complications in CHD often appear by age four, yet current diagnostic approaches do not capture ultra-early structural and cellular changes in the kidney.

- Once significant kidney damage has occurred, it is extraordinarily difficult to reverse. In fact, there are currently no known therapies that can halt or reverse kidney glomerular damage.

- Our data, together with epidemiologic studies, support the idea that routine kidney screening should be integrated into CHD care pathways, ideally from a very early age, with thresholds and follow-up tailored to genetic and environmental risk factors.

Beyond SMAD2 and CHD, the experimental framework we developed—combining iPSC-based disease modeling, CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, organ-on-a-chip technology, and integration with clinical data—offers a generalizable way to:

- Functionally test variants of uncertain significance in a human context.

- Map their impact on developmental trajectories and organ-specific cell types.

- Clarify pathogenicity and inform both risk stratification and potential therapeutic targets.

Thus, this project is not only about one gene or one disease. It is a blueprint for how we might systematically “decode” human variants across many organs and conditions,

The human side of a multi-year research project

The technical story of this paper is intertwined with the growth of my research lab, and the authorship list reflects the collaborative spirit in our research team. The contributing authors include graduate students (Rohan Bhattacharya and Hamidreza Arzaghi), undergraduates (Alekshyander Mishra and Sophia Leeman), and postdoctoral fellows/research scientists (Tarsha Ward and Titilola Kalejaiye). The first author, Rohan, was one of the first three Ph.D. students to join my lab. He initially worked on a different, but conceptually related, project. He was attempting to use genome engineering to generate isogenic human iPSC lines carrying high-risk APOL1 variants (a gene previously implicated in kidney disease but with a less understood pathway to pathogenicity) to examine how those mutations affect podocyte differentiation and function. It was an important question, squarely within our interest in podocyte biology and genetic kidney disease. But despite a lot of effort, the project did not progress as we had hoped. The APOL1 gene editing was challenging, timelines kept stretching, and the risk that it would take too long to even start the first set of cellular differentiation experiments needed to address the most important questions became concerning.

As a mentor, there are times when one must make a decision, even when it's uncomfortable: in this case, recognizing when a student needs to pivot, not because the science isn’t interesting, but because the risk profile has become somewhat misaligned with their training timeline, the high research cost, and the technical challenges of the work. After quite some time, I felt a growing responsibility to help Rohan move onto a project that would give him a strong and reasonable path to finishing his degree in a reasonable amount of time, with adequate supervision and a clearer experimental runway. Fortunately, when I finally made that decision, the groundwork was already in place for a successful outcome. I had already developed the methods for podocyte differentiation and the kidney glomerulus-on-a-chip culture system4,5 , which my research team and others have used to model aspects of kidney biology and diseases6–14. Additionally, the SMAD2 mutant iPSC lines were generated, characterized in the context of cardiac differentiation3 and made available to us by the Seidmans' labs. It was clear that this project could move forward quickly once the right student in my group took leadership and dedicated their effort to it.

Rohan happened to be the lab member to take on and work collaboratively with several lab members to complete the first phase of the study. He is hard-working, determined, and incredibly self-motivated. I suspect that after the challenges of the earlier project, he was especially eager to make tangible research progress. He is also one of the students who would regularly appear at my office door—or call or text me— to ask questions, discuss data, or get immediate feedback on experimental plans and troubleshooting. That kind of proactive engagement is also a strong predictor of scientific growth: it means the student is actively thinking, iterating, and taking ownership. He did not just “switch projects”; he synthesized his initial training and learning into a new framework and then pushed it forward with determination. The setbacks with his earlier work were not wasted effort; they became part of the foundation that allowed him to execute this complex, multi-layered study.

The human story of this paper also includes the peer review process, which was both long and constructive. The manuscript remained under review at Nature Biomedical Engineering for more than two years. Over that time, the reviewers asked for additional experiments, new datasets, and exploration of clinical cases related to our study. Importantly, the core conclusions never changed—but each round of work strengthened the evidence base, expanded the scope of our analyses, and further solidified the link between SMAD2 variants, early mesoderm and kidney development, and podocyte dysfunction.

As the principal investigator of the study, I had mixed feelings during this process. On one hand, the reviewers' feedback was, for the most part, thoughtful and constructive, and the paper was getting stronger with the revisions. On the other hand, I worried about the prolonged, high-stakes review cycle. A process of this length tests not only scientific rigor, but also resilience, patience, trust, and the ability to stay focused and motivated. Long reviews can also be incredibly costly in time, energy, and resources. Still, I am grateful that, in this case, the extended peer review dialogue did help strengthen our conclusions and, I believe, the paper's eventual impact. The process made visible the kind of quiet perseverance that is easy to overlook when one only sees the final published paper: a team’s collective effort to share a scientific discovery while supporting that journey over multiple years, not months.

This paper is also, in a very real sense, the realization of the promise Tarsha and I made as postdocs—to bring together our complementary perspectives and publish a human-focused disease model that connects developmental biology to clinical genetics. Her continuous involvement in this study helped transform that initial spark into a fully developed story, capturing the continuity of mentorship and collaboration across labs and institutions.

For me, the human side of this project is about all of these layers at once: the early conversations with Tarsha at Harvard; the decision to trust a new lab with a challenging, multi-organ question; the difficult pivot from a stalled project to one with clearer momentum; the long arc of peer review; and the way resilience and curiosity can turn technical experiences into discoveries. The final paper reflects not only the science we set out to do, but also the mentoring choices, foundational technologies, collaborations, and persistence that made it possible.

Looking ahead

This study addresses important questions and leaves us with many more questions, and that is a good thing. Among the questions:

- How do other mutations in SMAD2, including the many missense variants of uncertain significance, shape organ development across the heart, kidney, vasculature, and beyond?

- Can we develop scalable cellular and molecular assays to reclassify these variants based on functional impact?

- How can we translate early mechanistic insights into concrete changes in guidelines—for example, integrating genetic information and routine kidney screening into standard CHD care?

- And more broadly, how can we empower the next generation of scientists and clinicians to design models and clinical studies that reflect the complexity and interconnectedness of human organ systems?

As we continue this and related work in my lab, our focus includes discovering early biomarkers of kidney vulnerability and exploring regenerative or gene-based strategies to preserve function or reverse injury phenotypes in patients. But even before such therapies are available, the message emerging from this paper is clear: early detection and prevention are essential. It is far easier to preserve a functioning kidney than to rescue a failing one.

Ultimately, this "behind the paper" story is about more than a single publication. It is about a shift in how we conceptualize congenital diseases: not as isolated defects confined to one organ, but as systemic developmental processes shaped by shared genetic and molecular architectures. By building human models that reflect that complexity, we can move closer to care strategies that do the same.

References

- Bhattacharya, R. et al. Engineered human induced pluripotent stem cell models reveal altered podocytogenesis in congenital heart disease-associated SMAD2 mutations. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1–20 (2025).

- Musah, S. Decoding cell fate: human models reveal how SMAD2 variants shape development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 1–1 (2025).

- Ward, T. et al. Modeling SMAD2 Mutations in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Provides Insights Into Cardiovascular Disease Pathogenesis. J. Am. Hear. Assoc.: Cardiovasc. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 14, e036860 (2025).

- Musah, S., Dimitrakakis, N., Camacho, D. M., Church, G. M. & Ingber, D. E. Directed differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells into mature kidney podocytes and establishment of a Glomerulus Chip. Nat. Protoc. 13, 1662–1685 (2018).

- Musah, S. et al. Mature induced-pluripotent-stem-cell-derived human podocytes reconstitute kidney glomerular-capillary-wall function on a chip. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1, 0069 (2017).

- Mou, X. et al. A Biomimetic Electrospun Membrane Supports the Differentiation and Maturation of Kidney Epithelium from Human Stem Cells. Bioengineering 9, 188 (2022).

- Roye, Y., Miller, C., Kalejaiye, T. D. & Musah, S. A human stem cell-derived model reveals pathologic extracellular matrix remodeling in diabetic podocyte injury. Matrix Biol. Plus 100164 (2024).

- Roye, Y. et al. A Personalized Glomerulus Chip Engineered from Stem Cell-Derived Epithelium and Vascular Endothelium. Micromachines 12, 967 (2021).

- Kalejaiye, T. D., Bhattacharya, R. & Musah, S. A Vascularized Human Organ Chip Reveals SARS-CoV-2 Susceptibility in Developmentally Guided Tissue Maturation. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 1–19 (2025).

- Burt, M. A., Kalejaiye, T. D., Bhattacharya, R., Dimitrakakis, N. & Musah, S. Adriamycin-Induced Podocyte Injury Disrupts the YAP-TEAD1 Axis and Downregulates Cyr61 and CTGF Expression. Acs Chem Biol 17, 3341–3351 (2021).

- Mou, X., Shah, J., Roye, Y., Du, C. & Musah, S. An ultrathin membrane mediates tissue-specific morphogenesis and barrier function in a human kidney chip. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn2689 (2024).

- Roye, Y. & Musah, S. Isogenic Kidney Glomerulus Chip Engineered from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. J. Vis. Exp. (2022).

- Zhang, Y. & Musah, S. Mechanosensitive Differentiation of Human iPS Cell-Derived Podocytes. Bioengineering 11, 1038 (2024).

- Kalejaiye, T. D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Employ BSG/CD147 and ACE2 Receptors to Directly Infect Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Kidney Podocytes. Frontiers Cell Dev Biology 10, 855340 (2022).

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Biomedical Engineering

This journal aspires to become the most prominent publishing venue in biomedical engineering by bringing together the most important advances in the discipline, enhancing their visibility, and providing overviews of the state of the art in each field.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Such a great piece!!