Beyond the Mechanistic: Restoring the 'Human' in STEM Education

Published in Education and Philosophy & Religion

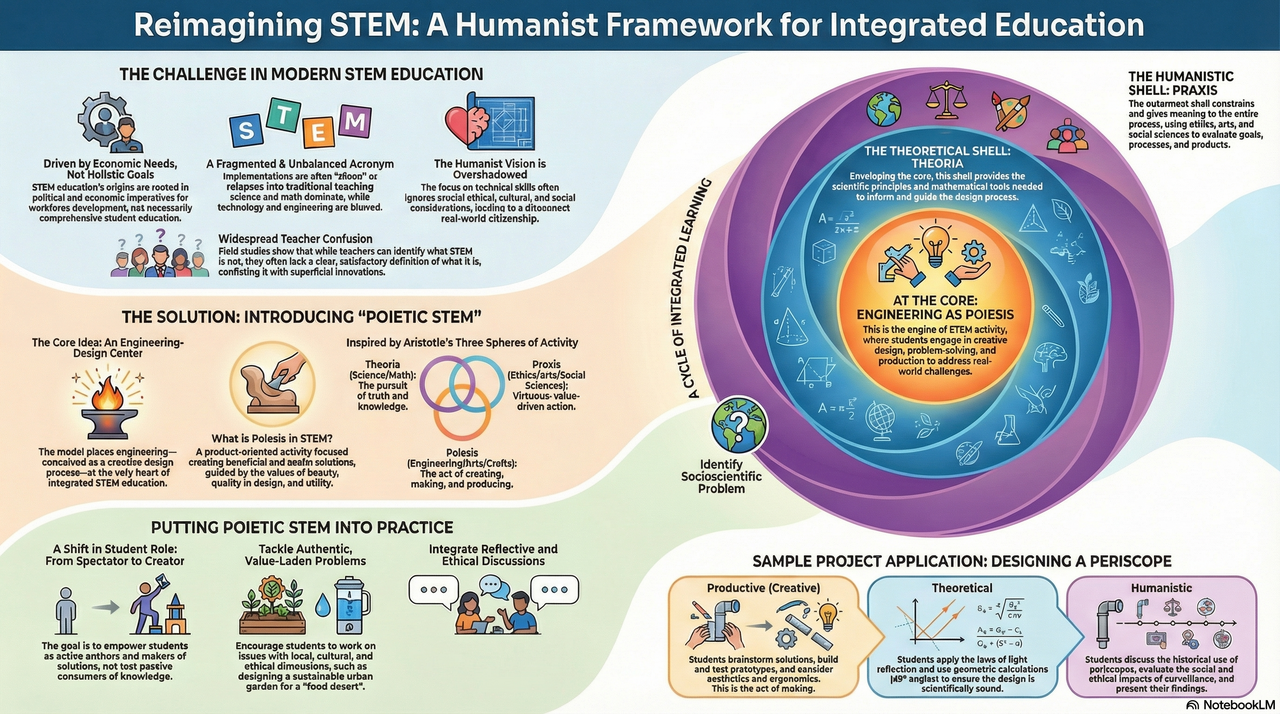

Over the past two decades, STEM education has risen from a policy buzzword to a global educational movement. Its promise is compelling: to prepare new generations capable of navigating complex sociotechnical landscapes through interdisciplinary knowledge, problem-solving, and innovation. Yet as my co-authors and I progressed through our research, we increasingly felt that a deeper issue was being overshadowed: when STEM is framed solely as an engine for workforce development and economic competitiveness, something essentially human is lost. The very practices intended to empower learners risk becoming mechanistic, instrumental, and estranged from the ethical, aesthetic, and cultural dimensions of human life.

Our recently published article, “Theoretical Suggestions for the Nature of Integrated STEM Education: Notes on a ‘Poietic’ STEM”, emerged from years of grappling with this tension. We wanted to understand—in a rigorous philosophical sense—what kind of educational activity STEM actually is, what kind of human being it presupposes, and what kind of society it ultimately serves. This required going beyond the acronym and its common policy narratives and instead revisiting the intellectual traditions that have shaped scientific and technical knowledge.

Where the Study Came From: A Common Unease Among Researchers

The article grew organically from conversations among the four of us, each coming from different intellectual traditions—science education, chemistry education, philosophy of science, and the epistemology of design. We shared a concern: despite the widespread enthusiasm for integrated STEM education, the field still lacked a coherent theoretical foundation. Teachers often articulated what STEM “is not”, but struggled to articulate what STEM is. Implementation problems—fragmented curricula, superficial integrations, neglect of ethics and culture—seemed to stem from this conceptual vagueness.

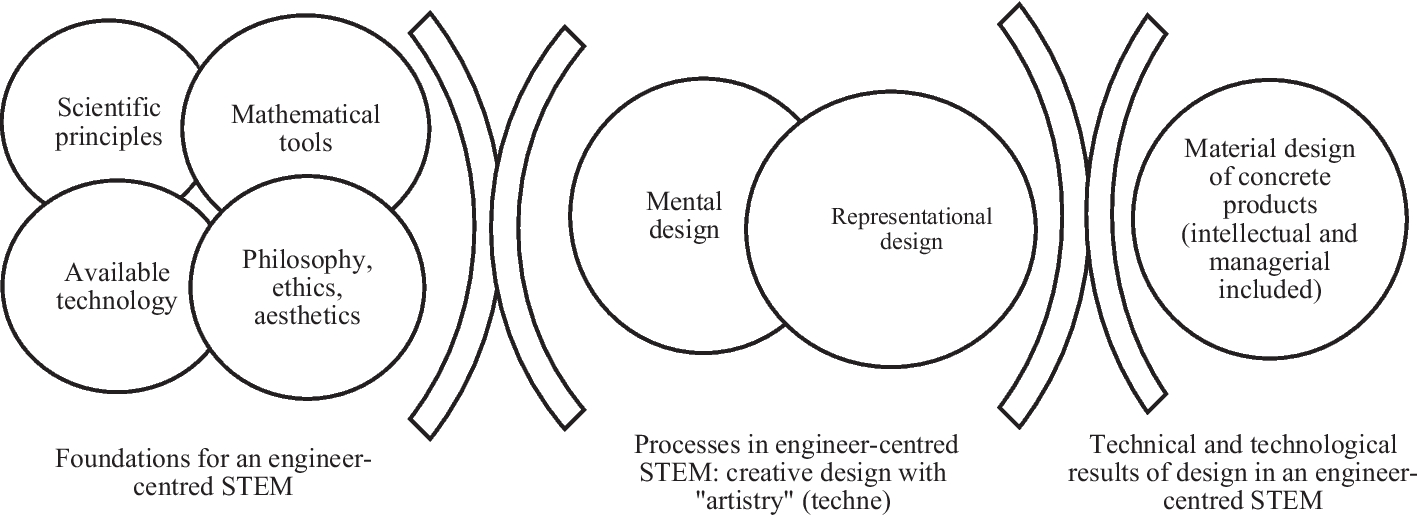

We also shared a stronger intuition: engineering, especially in its design-based form, was quietly becoming the gravitational center of STEM, yet this shift had not been theorized adequately. Could an engineering-based perspective offer a genuine integrative framework? And if so, what kind of engineering are we talking about?

The Turning Point: Revisiting Aristotle and the Concept of Poiesis

Our conceptual breakthrough came when we revisited Aristotle’s classification of human intellectual activity—theoria (seeking truth), praxis (virtuous action), and poiesis (creative production). Many of the challenges in STEM, we realized, revolved around a neglected question: What does it mean to design? And more importantly, what kind of knowing is involved in designing something for human use?

Modern engineering, in its essence, is a poietic activity:

- it combines theoretical knowledge (science and mathematics),

- practical wisdom (ethics, cultural context, human needs), and

- creative-technological skill (techne).

This framed STEM not merely as a collection of disciplines, but as a unified human activity: producing meaningful, useful, and ethically situated products—material or conceptual. This opened an entirely new way to think about STEM education.

Behind the Scenes: Constructing the Philosophical Model

The writing process involved a continuous back-and-forth between conceptual analysis and practical classroom realities. We spent a great deal of time reviewing the nature-of-science literature, characterizations of engineering practice, and debates around integrated curricula. But the heart of the framework emerged when we realized that the Aristotelian triad could map cleanly onto contemporary educational constructs:

- Theoria → Scientific and mathematical literacy

- Praxis → Ethical reasoning, socioscientific decision-making, reflective action

- Poiesis → Engineering design, creation, innovation

The conceptual leap was to reorganize these not as separate categories, but as layers surrounding a design-oriented STEM core. In this system, engineering is not merely an applied outcome of science and math; it becomes the organizing principle that meaningfully integrates them. Yet engineering itself must be framed not narrowly as technical problem-solving, but as a humanistic, value-informed activity.

What We Mean by “Poietic STEM”

In the paper, we propose poietic STEM education as an approach characterized by:

- Design as the central integrative engine, rather than science or mathematics alone.

- Products understood broadly: not only devices, but symbolic, conceptual, organizational, artistic, or ethical outcomes.

- A strong humanistic orientation, integrating ethics, aesthetics, cultural knowledge, and social awareness.

- Learning cycles in which students design, test, critique, and iterate solutions to real sociotechnical problems.

- A classroom culture modeled on responsible creativity, where making and reasoning are inseparable.

In practical terms, this means that a STEM activity should not merely ask students to “build a bridge” or “design a periscope”, but rather to situate their designs ethically, socially, and aesthetically:

Who benefits from this solution? What are the unintended consequences? How does it fit into human experience?

Methodological Notes: How We Approached the Study

Although the paper is theoretical, it is grounded in:

- systematic reviews of literature on the nature of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics;

- the conceptual history of engineering design;

- philosophical analysis (Aristotelian, post-positivist, and post-humanist perspectives);

- existing STEM frameworks and national curriculum standards;

- and practical examples from classroom-based STEM implementations.

This triangulation helped us build a model that is philosophical in foundation yet pedagogically actionable.

Why This Matters Now

The current global landscape places enormous pressure on schools to produce “technically skilled” individuals. However, major societal challenges—AI ethics, climate engineering, energy transitions, biotechnology—are not merely technical; they are profoundly ethical, cultural, and political. The students we teach today will face decisions that cannot be solved through algorithmic thinking or technical optimization alone.

A STEM education that neglects this complexity risks producing competent technicians rather than responsible creators. A poietic STEM, by contrast, aims to cultivate students who can think with precision, act with ethical awareness, and design with imagination.

Invitation for Discussion

This proposal is not presented as a definitive framework but as an invitation. We believe that integrating classical philosophical categories with contemporary engineering-design practice offers a promising path for reconceptualizing STEM education.

We would be delighted to hear how colleagues across disciplines—scientists, engineers, educators, philosophers, designers—interpret, challenge, and expand upon this poietic approach. How might such a perspective reshape curriculum design, teacher education, assessment, or policy?

Your reflections and critiques will be invaluable as we continue developing this line of inquiry.

Follow the Topic

-

Science & Education

This is the official journal of the IHPST group, which focuses on enhancing teaching, learning, and curricula in science and mathematics through historical, philosophical, and sociological approaches.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Futurizing Science Education: historical, philosophical, and sociological aspects of futures literacy for science education

The mounting uncertainties of our time—from environmental and climatic disruptions to rapid technological shifts, pandemics, and socio-political crises—have renewed attention to the importance of the future. These global challenges highlight the need for education to cultivate learners’ capacities for anticipation, imagination, and critical engagement with multiple possible futures.

Futures Studies, an interdisciplinary field devoted to the systematic exploration of the future, has emerged partly to critique deterministic and techno-solutionist narratives that compress the future into an extended present and foreclose the possibility of alternatives (Poli, 2024). Such narratives can fuel “future anxiety” (Zaleski, 1996) and often resonate with neoliberal agendas that seek to control—or even colonize—the future. In contrast, Futures Studies expands temporal horizons and foregrounds the plural, open-ended nature of future possibilities (Paura, 2024). To support this orientation, it offers a repertoire of theoretical frameworks and methodological tools for developing anticipatory capacities (Miller, 2018; Poli, 2024), including foresight methods, scenario construction, systems thinking, and research on uncertainty, complexity, and long-term reasoning (e.g. Motti, 2025).

In recent years, international policy agendas from UNESCO, the OECD, and other international institutions have placed future-oriented thinking at the centre of educational reform. UNESCO’s expanding investment in futures literacy (e.g. Miller, 2018) and initiatives such as the OECD’s Anticipation–Action–Reflection cycle (OECD, 2019), UNESCO’s Reimagining Our Futures Together (UNESCO, 2021) underscore this direction. Similar orientations appear in the European Commission’s Strategic Foresight programme (European Commission, 2017), in the GreenComp framework (Bianchi et al., 2022), in Latin America educational frameworks (UNESCO 2017), in Africa (UNESCO, 2025), and in Asia (UNDP RBAP, 2022a; 2022b).

This international momentum has increasingly shaped the priorities of science education research. Futures literacy has been officially recognised as a key competence by the European Science Education Research Association (ESERA), which has established a dedicated conference strand and launched a Special Interest Group on this topic. Several EU-funded projects—such as I SEE, FEDORA,Teff, and FEDORAS—have investigated how to integrate futures thinking into science teaching (Levrini et al., 2019; 2021), contributed to the development of a Future-Oriented Science Education Manifesto (Bol et al., 2023), and produced recommendations for embedding anticipatory competences in science education policy and practice (Rasa et al., 2023). Collectively, this emerging scholarship demonstrates that the increasing attention to futures in science education is not an isolated academic trend but part of a broader international shift toward anticipatory, imaginative, and future-oriented educational practices.

Even as calls to “futurize” education gain visibility, they are not always accompanied by sustained engagement with the theoretical, historical, epistemological, and socio-cultural challenges that futurizing entails. This Special Issue responds to that need. In line with the mission of Science & Education, it invites researchers in the history, philosophy, and sociology of science and science education to examine the foundations of Futures Studies and their implications for science education. Both theoretical and empirical contributions are welcome

Submissions are by call for papers (open call) and there is no maximum word length.

Submissions should be written according to the journal’s submission guidelines, available here. Online submission: please use the journal's Online Manuscript Submission System (Editorial Manager) accessible here. Please note that paper submissions via email are not accepted. All papers will undergo the journal's standard review procedure (double-blind peer review), according to the journal's Peer Review Policy, Process, and Guidance. Reviewers will be selected according to the Peer Reviewer Selection policies. This journal offers the option to publish Open Access. You are allowed to publish Open Access through Open Choice. Please explore the OA options available through your institution by referring to our list of OA Transformative Agreements. For any questions, please contact the Lead Guest Editor, Olivia Levrini (olivia.levrini2@unibo.it).

Timeline

December 11, 2025: Submissions open.

June 30, 2026: Submissions close.

Submissions may address, but are not limited to, the following themes:

- Historical and philosophical roots of futures studies and their relevance for science education

- Socio-cultural perspectives on futures thinking and its role in decolonizing future and promoting, through science education, plural and open-ended images of the future

- The contribution of futures-oriented science education to emancipatory educational policies, approaches, and practices, and to social justice

- Research-based educational approaches and activities designed to foster positive, creative, and empowered attitudes toward the futures

- Empirical research on classroom practices, curricula, or teacher education involving futures thinking, including approaches and tools to assess the development of futures-thinking skills

- Critical examinations of techno-solutionism, colonial framings, and neo-positivistic narratives of scientific progress in textbooks, curricula, and policy documents, and proposals for how to “futurize” these materials

- Methodological contributions on how to study “the futures” within educational research

- Interdisciplinary or comparative studies on futures literacy across science, mathematics, technology, social sciences, and humanities education

References

Bianchi, G., Pisiotis, U., & Cabrera Giraldez, M. (2022). GreenComp—The European sustainability competence framework (EUR 30955 EN). Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/13286

Bol, E., Laherto, A., Levrini, O., Erduran, S., Conti, F., Tola, E., Troncoso, A., Tasquier, G., Rasa, T., & Pucetaite, R. (2023). Future-oriented science education manifesto.

European Commission (2017). Strategic Foresight Primer. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2872/71492

Levrini, O., Tasquier, G., Branchetti, L., & Barelli, E. (2019). Developing future-scaffolding skills through science education. International Journal of Science Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2019.1693080

Levrini, O., Tasquier, G., Barelli, E., Laherto, A., Palmgren, E. K., Branchetti, L., & Wilson, C. (2021). Recognition and operationalization of future-scaffolding skills. Science Education. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21612

Miller, R. (Ed.). (2018). Transforming the Future: Anticipation in the 21st Century. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351048002

Motti, Victor V. (2025). Playbook of Foresight: Designing Strategic Conversations for Transformation and Resilience, USA: Washington, D.C., Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing

OECD. (2019). OECD Learning Compass 2030: Concept Note. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/about/projects/edu/education-2040/1-1-learning-compass/OECD_Learning_Compass_2030_Concept_Note_Series.pdf

Paura, R. (2024). About the History of Futures Studies. In Poli (2024) (Ed).Handbook of Futures Studies. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781035301607.00008

Rasa, T., Laherto, A., Levrini, O., Bol, E. & Tasquier, G. (2023). Framework to futurise science education - Deliverable 3.3 (V1.0). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7519069

Poli, R. (Ed.). (2024). Handbook of futures studies. Edward Elgar Publishing.

UNESCO (2017). La nueva agenda educativa para América Latina: Los objetivos para 2030. Universidad de Alcalá; Fundación Santillana.

UNESCO (2021). Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education. https://doi.org/10.54675/ASRB4722

UNESCO (2025). Transforming Knowledge for Africa’s Future. PDF (https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000395728/PDF/395728eng.pdf.multi)

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific. (2022a). Foresight playbook. UNDP.

https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2022-08/UNDP-RBAP-Foresight-Playbook-2022.pdf

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific. (2022b). Reimagining development in Asia and the Pacific: A synthesis report. UNDP.

Zaleski, Z. (1996). Future anxiety: Concept, measurement, and preliminary research. Personality and Individual Differences, 21(2), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(96)00070-0

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Interesting article! Maybe we should abondon the common setup, where one educator works with the students and step towards a situation where 2-3 educators with different experitise are working with the students formulating more sophisticated solutions. Learning by observing discussion.

This is an intriguing notion. We are amenable to entertaining this possibility.

Dear Dr. Davut Saritas, your proposal for a 'Poetic STEM' is a profound and necessary response to the mechanical reductionism characterizing our technical age. As an independent researcher, I have developed a framework called 'Sovereignty Algebra' that seeks to provide the mathematical and ontological grounding for the 'Human Side' you aim to restore.

My thesis starts from the premise that 'The Human is the Author of the Universe and its Only Consciousness'. While matter is inherently silent, human consciousness is the 'emergent phenomenon' that gives this silence its existential meaning. Within this context, I have translated the Aristotelian concepts you mentioned Poiesis (Creation) and Phronesis (Practical Wisdom) into a core mathematical variable: (F), representing 'Divine Commission' (Taklif) and moral sovereignty.

I argue in my research that for STEM education to transition from a 'utilitarian' approach to a 'responsibly human' one, we must integrate this variable (F) as a 'Sovereign Veto' within the machine's algorithmic architecture. Your pivotal question 'What kind of human does STEM education assume?' lies at the heart of my 'Coherence Equation' (M_\theta = F/B). We must teach students how to code 'Integrity' into systems; otherwise, we are merely training them to be 'functional tools' eventually outpaced by the machine’s computational efficiency.

I am honored to invite you and interested colleagues to explore the mathematical details and logical proofs of these equations on my academic profile:

https://independent.academia.edu/FatihaBouzid2

I look forward to discussing how 'Sovereignty Algebra' can support your vision for a technical education that does not just build machines, but actively protects human sovereignty and the soul