Big fish trouble in Europe, especially the Mediterranean

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Marine fish are a diverse group of animals that play important roles in marine ecosystems, as well as being a major food source for marine and terrestrial mammals, notably humans. Nowhere is this more the case than in Europe, where we have been fishing for millennia. In spite of this, there are still “some” fish left in the sea, but not plenty. Exactly how many and what types, or species, are left, is revealed in our paper “'Coherent assessments of Europe’s marine fishes show regional divergence and megafauna loss”[1]. Large fish are at risk in Europe, the bigger the fish species the more likely it is to be threatened with extinction: in fact, over 50% of all species which grow to a size of 1.5 metres or more are threatened with extinction. Many of these are cartilaginous fish (sharks, skates and rays), but they also include sturgeons and some other fish. Large fish species are more susceptible to threats such as overfishing, because they grow slower, take longer to mature and have fewer offspring; they are also more sought after.

The Angelshark (Squatina squatina) typifies the fish most at risk of extinction: it grows to a large size and is cartilaginous, so it has characteristics which make it less resilient. Once common throughout Europe this species is now mostly rare or absent throughout much of its historical range. Picture courtesy of Tony Gilbert.

This work came out of a major effort to assess the extinction risk of all European fish carried out by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to produce the European Red List of Marine Fishes[2]. This assessed over 1000 different species, but we also wanted to know if this assessment was compatible with another source of advice provided by other intergovernmental agencies on the status of commercial fish “stocks”. Stocks are particular populations of a species (typically in a geographic area), such that any one species might have many stocks. These fisheries agencies assess whether stocks are overfished or not, and go on to provide advice on how much can be taken to ensure that the stock is sustainable, through quotas (catch limits). In the past, information on these two types of assessments has been conflicting: although it would be consistent for an overfished stock to be threatened, it is not the case for sustainable stocks to be so. We found that the two systems were coherent: no fish stock deemed sustainable by the fisheries agencies was considered threatened by IUCN. It was the case that some species deemed of “Least Concern” were overfished, but this is consistent because the two systems represent graduated indicators of status, with the fisheries agencies providing the first level of concern (overfishing).

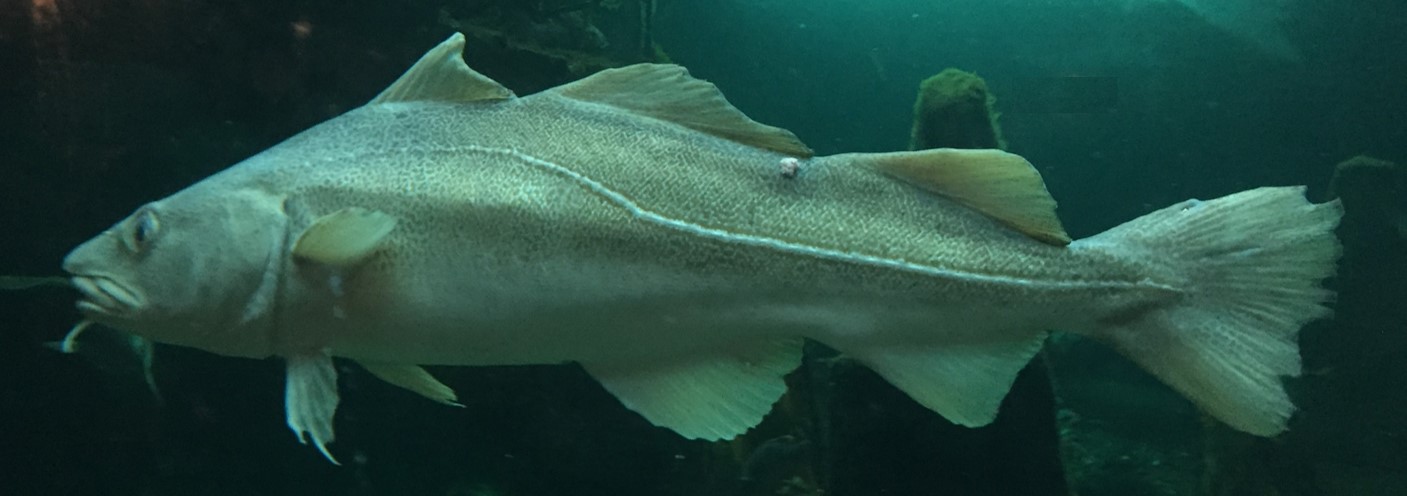

The Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua): although some stocks of cod are overfished, the species is not considered threatened with extinction in Europe, largely because stocks such as north east Arctic cod are doing very well; even the North Sea cod stock has almost recovered, after decades of overfishing. Picture credit: Paul Fernandes.

We then examined the status of commercial fish stocks all around Europe and found a remarkable geographic contrast. In the Northeast Atlantic, almost twice as many stocks were sustainably fished (19) as overfished (10); 8 stocks were recovering (the fishing rate is not high, but their populations are small); and 19 were declining (their populations are healthy, but the fishing rate is now too high). However, in the Mediterranean Sea, almost all stocks examined in our study were overfished (36 of 39) and not one was sustainable. This comes down to how the areas are managed and the unique nature of the fishing communities in the two areas. In the Northeast Atlantic, there is a complex (& expensive) fishery monitoring and enforcement system, which sets quotas and other regulations to keep fish stocks healthy. In the Mediterranean, however, in addition to the economic challenges of the surrounding nations, such monitoring & enforcement would be even more expensive, because there are many more fishermen scattered in many small fishing ports. Hence there are largely no quotas in the Mediterranean, only some protected areas and some limits on the amount of fishing time; the area also has more pressing economic and food security concerns.

A typical scene in the Mediterranean showing a fishing village which has become a popular tourist destination (an example of "Blue Growth"). Throughout the Mediterranean, fishing is more like a subsistence culture with thousands of fishermen operating from small ports like these, making enforcement and monitoring of catches logistically challenging and prohibitively expensive. Picture credit: Paris Vasilakopoulos.

We have highlighted two major issues for Europe’s fish: the threats to large fish, the so- called megafauna, and the overfishing problem in the Mediterranean. Europe is proceeding with a Blue Growth agenda, aiming to expand its use of marine space in aquaculture, mining, renewable energy, tourism and biotechnology: as it does so it needs to take care of the megafauna and improve fishery management in the Mediterranean.

The paper in Nature Ecology & Evolution is here: http://go.nature.com/2sgLOoM

[1] Fernandes, P.G. et al Coherent assessments of Europe’s marine fishes show regional divergence and megafauna loss. Nature Ecol. Evol. DOI 10.1038/s41559-017-0170 (2017).

[2] Nieto, A. et al. European Red List of Marine Fishes (Publications Office of the European Union, 2015).

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in