Buruli ulcer transmission and the philosophy of science

Published in Microbiology and Philosophy & Religion

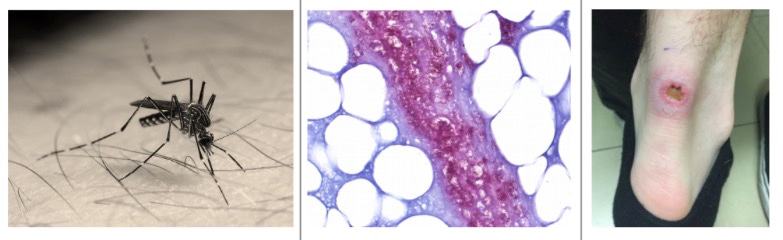

Buruli ulcer is a destructive, toxin mediated, progressive infection of skin and soft tissue. When diagnosis is delayed or treatment not available, sufferers can be left with permanent functional and cosmetic deformity.

A characteristic of Buruli is that it is geographically restricted – people acquire infection only in specific parts of specific countries. It is necessary to enter one of these places to be at risk for Buruli. As Bob Marley might have sung, “No visit, no cry”.

In 1998, in response to a growing epidemic of Buruli ulcer in West African children, WHO launched the Global Buruli Ulcer Initiative (GBUI). This highly successful group, now absorbed under Neglected Tropical Skin Diseases, mapped and identified cases, worked to de-stigmatise Buruli and led the paradigm shift from plastic surgery to curative antibiotic therapy.

Meanwhile in temperate Victoria, Australia, we also were experiencing an epidemic of Buruli. Our situation here was very different from Africa, yet the disease is very similar, and the diagnostic PCR first developed in Melbourne is the definitive diagnostic test for Buruli used everywhere.

While our African colleagues were caring for Buruli sufferers who typically lived in subsistence farming communities along tropical inland river valleys, we were seeing outbreaks in temperate coastal towns and suburban streets. WHO hoped that with our greater resources we could help identify the mysterious mode of transmission and environmental reservoir of Mycobacterium ulcerans – two big unanswered question that were the keys to being able to prevent Buruli in the future.

After some early false starts, we landed on a new bold idea. Maybe mosquitoes transmit Mycobacterium ulcerans? A possible role for insects was first suggested to us when colleagues working in Benin detected M. ulcerans in water bugs using the PCR we had invented. In Victoria we were seeing patients who had very brief exposures to the endemic areas we had mapped, sometimes just a few hours on one particular day, and we noted that Buruli lesions were typically found on the body where mosquitoes bite.

In 2007 we published two key papers, the first reporting that when you trap mosquitoes in a Victorian endemic area they test positive for M. ulcerans DNA at a rate of about 4/1000. The second paper was a case control study reporting that use of insect repellent appeared to protect people against Buruli ulcer. We followed up by trapping local possums and found that a quarter of them had Buruli ulcer and proposed that mosquitoes become contaminated with M. ulcerans from infected possums.

Mycobacterium ulcerans was not a free-living environmental pathogen after all. Buruli is instead a zoonosis transmitted to humans by mosquitoes from a possum reservoir.

“Science must begin with myths, and the criticism of myths” said Karl Popper, the renowned philosopher of science. With these publications we were confronting the paradigm of transmission by direct environmental exposure to water or soil - probably a myth. However, as is often the case when dogma is challenged, it was we who were viewed as the myth makers, at least initially.

Karl Popper also said that new theories should be bold, but to qualify as genuinely scientific a second type of boldness must accompany them. A bold new theory must be stated in a way that would allow it to be falsified with new tests when new opportunities to test arise.

So, when we became aware of a big new Buruli outbreak on the Mornington Peninsula near Melbourne, distinct from where we had worked previously, we set out to falsify our bold theory. Once again we trapped and tested mosquitoes near the homes of human cases. We found the same result, with about the same proportion positive. This time we went further and used advanced molecular techniques to show that individual mosquitoes have strains of M. ulcerans on them or in them that are indistinguishable from those we isolate by culture from humans and possums with Buruli (read the full article in Nature Microbiology here).

Victoria recorded 363 cases of human Buruli ulcer in 2023, an all time record. We know that Buruli here is transmitted to humans during the mosquito season, and not at other times. We know that it occurs on the parts of the body that are bitten by mosquitoes. We know that insect repellent seems to protect you. We know that the mosquitoes that bite humans in Buruli endemic areas have both human and possum blood in them and we know that the strains of M. ulcerans that cause human Buruli are carried by mosquitoes that bite us.

We have failed to falsify our bold new theory, but we are wise enough to know this may not be the end of the story. In fact Karl Popper also reminds us that science is the art of systematic oversimplification and that the game of science has in principle no end. Nevertheless, we now know enough to inform our local public health colleagues with great confidence that if they can assist people to reduce mosquito bites they can be confident they will also reduce the incidence of Buruli ulcer, at least in this part of the world.

Paul Johnson and Tim Stinear, Melbourne, Australia

Image: Aedes notoscriptus mosquito; high-powered histological section of human Buruli ulcer showing myriads of Mycobacterium ulcerans cells [crimson] surrounded by necrotic fat; PCR-confirmed case of early category 1 Buruli ulcer (young man, Victoria, Australia)

Image attributions: Mosquito image https://www.flickr.com/photos/hlydecker/45461453381/ Histology image: Professor John Hayman; Buruli Case image: Professor Paul Johnson, Austin Health Infectious Diseases Clinic, Melbourne, Australia (with permission). See also https://paul-johnson-buruli.com

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Microbiology

An online-only monthly journal interested in all aspects of microorganisms, be it their evolution, physiology and cell biology; their interactions with each other, with a host or with an environment; or their societal significance.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

The Clinical Microbiome

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 11, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in