Can data analytics stop credit card fraud before it happens?

Published in Business & Management

Card-payment fraud is not merely an operational nuisance: it compresses margins, increases chargeback costs, degrades customer experience, and ultimately affects competitiveness. A recent study proposes a pragmatic approach—combining merchant-size segmentation, unsupervised models for preventive rules, and supervised models for alerts—and quantifies how much fraud could be avoided in a real payment-gateway setting in Latin America.

Analytics (and machine learning) in the service of commerce

The study analyzes 221,292 anonymized transactions from a payment gateway serving Latin American merchants (year 2022), described by 163 variables spanning categorical, temporal, and numerical fields. The core intuition is straightforward: fraud patterns differ substantially across merchants, and therefore a single model should not be expected to perform equally well for a small business and a large retailer.

Methodological design (without sacrificing rigor)

The paper decomposes the problem into two distinct operational objectives:

-

Prevention (pre-authorization or near-real-time gating): identify actionable fraud patterns to enable automatic rejection or manual validation using unsupervised clustering.

-

Alerting (post-approval monitoring): classify recent transactions as fraud / non-fraud and produce a risk signal using supervised learning.

To ensure operational relevance, the authors first segment merchants by size using an RFM-style (Recency–Frequency–Monetary) scheme and then fit models per stratum.

Central finding: merchant size changes the “best” model

The most meaningful result is not that “one model wins,” but that different models dominate in different segments:

-

Small merchants: k-means performs best for prevention, yielding rules that could block ~85% of fraud while avoiding substantial disruption to legitimate transactions.

-

Mid-sized merchants: PAM with Gower distance is strongest, with an estimated preventive effectiveness around 63%.

-

Large merchants: PAM (Gower) again leads, though with a lower stop rate, around 48%.

Overall, the study reports that applying the identified approaches could have prevented roughly 48% to 85% of fraud, depending on merchant size.

What about fraud “alerts” (when you cannot auto-decline)?

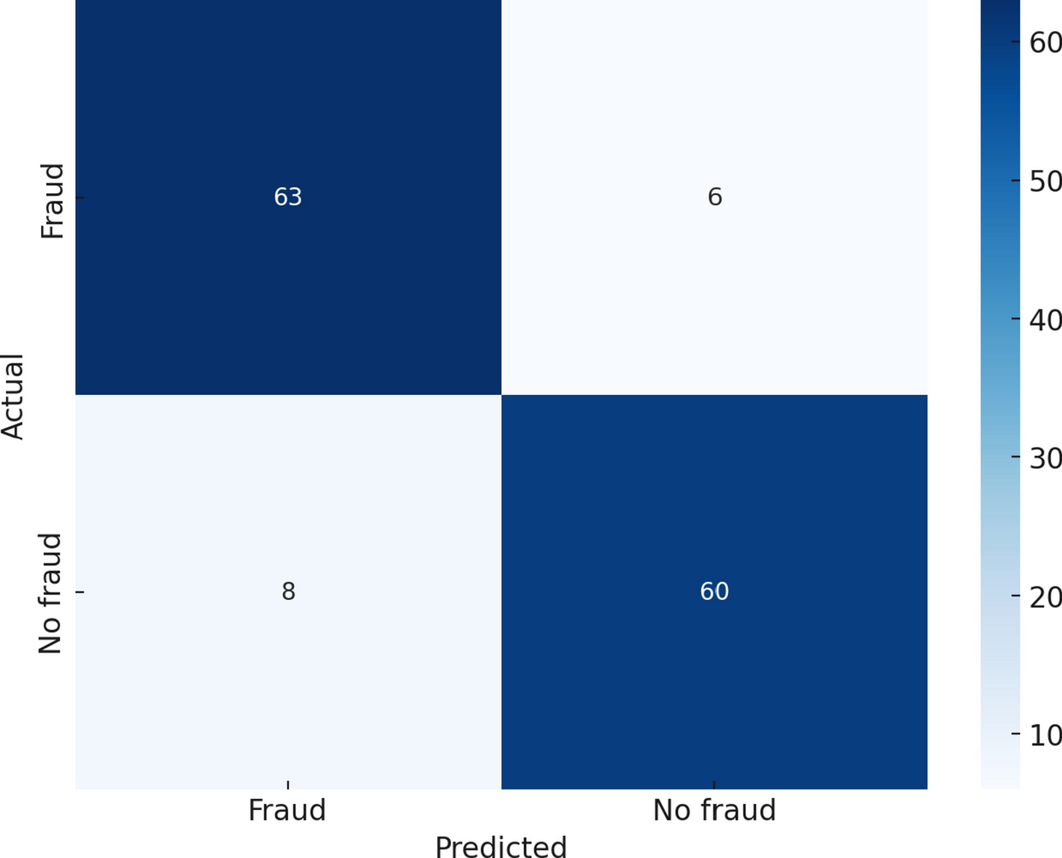

For the detection/alerting component, the authors compare several supervised classifiers (MLP, Random Forest, logistic regression, decision trees, Naïve Bayes, SVM) using standard performance metrics (accuracy, sensitivity/recall, specificity, and related measures):

-

Small merchants: MLP provides the strongest balance, with 90% accuracy and 91% sensitivity (ability to capture fraudulent cases).

-

Mid-sized merchants: Random Forest reaches 89% accuracy, though the paper emphasizes that MLP may be preferable when maximizing sensitivity (capturing fraud) is the overriding objective while maintaining solid overall performance.

-

Large merchants: Random Forest (86%) and MLP (85%) are close in accuracy; MLP stands out in sensitivity (87%), which is advantageous when the cost of false negatives is high.

In addition, the authors recommend maintaining “backup” models for retraining and operational continuity (e.g., Random Forest or a Gini-based decision tree), recognizing that fraud tactics evolve and adversaries adapt.

How reliable are these results?

The paper provides quantitative support for segmentation by merchant size:

-

A single “global” model yields AUC 0.789 and F1 0.46.

-

Size-segmented models improve substantially—for example, AUC 0.901 (small), 0.864 (mid-sized), and 0.852 (large)—with corresponding gains in F1.

The segmentation rationale is further supported by evidence of statistical heterogeneity and a population stability indicator (PSI) consistent with meaningful differences across strata.

From the paper to practice: optimizing costs, not only accuracy

A particularly operationally relevant element is that decision thresholds are not selected heuristically. The authors define an expected-cost framework contrasting the cost of missed fraud versus manual review, using a 10:1 ratio (e.g., 100 USD vs. 10 USD), and then select the threshold that minimizes expected cost by segment.

Illustrative optima reported include:

-

Small merchants: 25% threshold and cluster limit <300

-

Mid-sized merchants: 10% and <300

-

Large merchants: 10% without a limit

Implications: a realistic roadmap (and key cautions)

The paper does not present a “silver bullet.” It explicitly highlights the need for periodic retraining (suggesting approximately every six months) because fraud patterns shift over time. In terms of governance and implementation, it recommends:

-

strengthening technological infrastructure (especially among SMEs),

-

investing in analytical and ML capabilities,

-

promoting collaboration among merchants, banks, and regulators (with anonymized data),

-

protecting privacy and maintaining user trust.

Source: Rugeles Diaz, L. T., Echarte Fernández, M. Á., Jorge-Vázquez, J., & Náñez Alonso, S. L. (2025). Data analytics to prevent retail credit card fraud: empirical evidence from Latin America. Financial Innovation, 11:137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-025-00879-5

Follow the Topic

-

Financial Innovation

This is an open access journal, providing a platform for the exchange of research findings across all aspects of financial innovation.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in