Can we have our cake and eat it too? The environmental and socio-economic impacts of ten decarbonisation policy instruments to foster a net-zero future

Published in Sustainability

One of the toughest challenges of teaching about policies to shape innovation in energy technologies is to make sense of all the evidence regarding the impact that different policy instruments have on outcomes that are of interest to society. The complexity of environmental problems, combined with several other economic and socio-political challenges such as ensuring fairness and promoting competitiveness, have put great pressure on building a well-rounded, stronger understanding of how to design effective solutions to tackle climate change. This is even more true given the COVID-19 pandemic we are currently facing.

But synthetizing evidence and bringing all the pieces of this complex puzzle together is challenging for academics, policy makers or civil society alike. We realized this in our teaching as well as in interactions with policy makers and other stakeholders.

Indeed, the heterogeneity in academic evidence translates into uncertainty for policy makers regarding what instruments to choose when pursuing different or multiple goals. Within the EU research arena, the need for more clarity on these matters has been explicit for a while. For instance, the H2020 research funding program itself contained several calls for proposals focusing on the importance of developing knowledge on how to meet decarbonisation, innovation, competitiveness, labour markets goals while addressing the challenges of carbon-intensive regions and advancing equity. So, by the time the 2015-2016 H2020 funding calls opened, we jumped to the opportunity of focussing a task, within a larger project proposal, to the systematic evaluation of what the literature says about the impact of specific policy instruments on a range of societal goals.

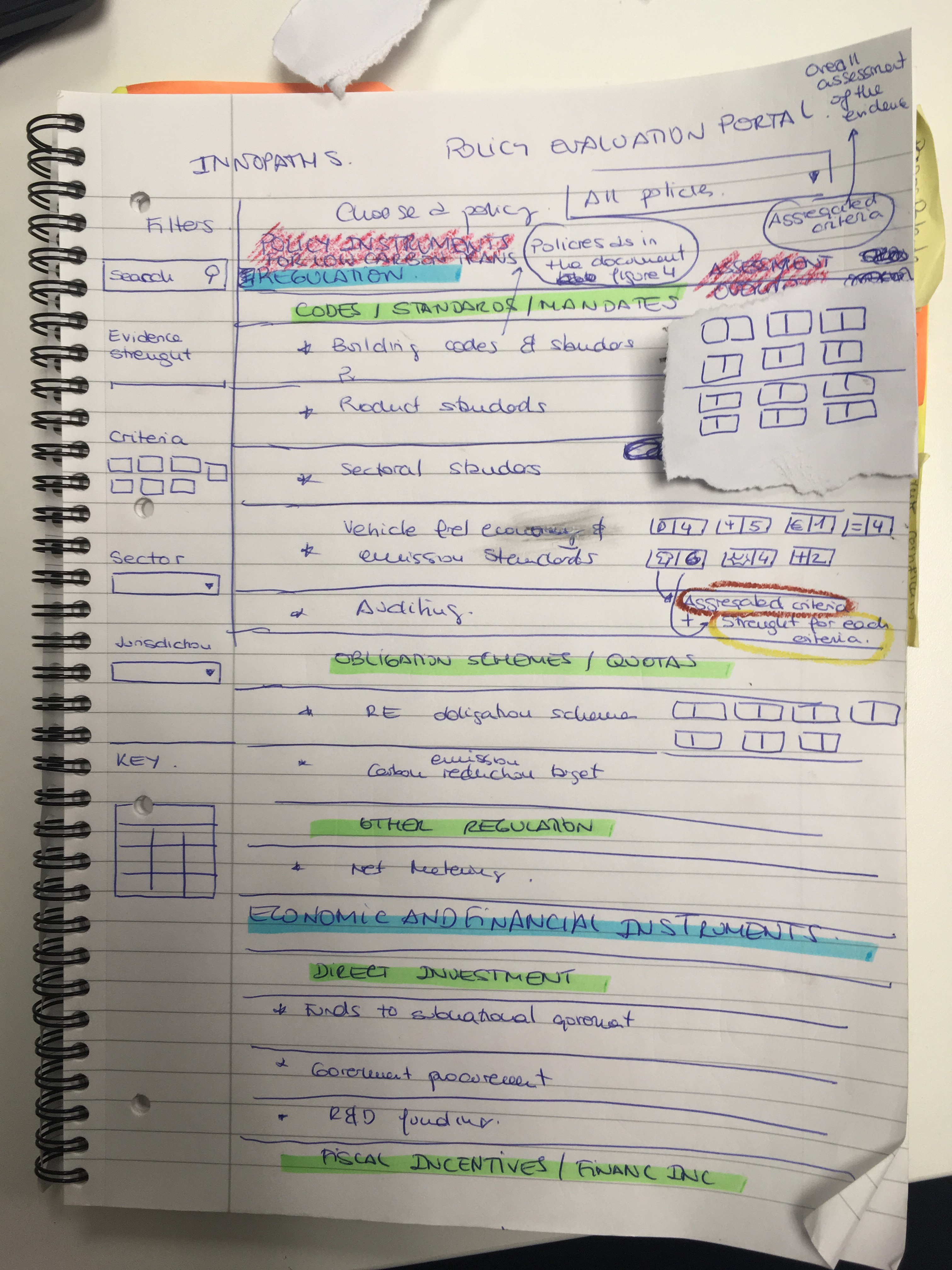

And lucky for us, the project proposal was funded. Starting December 1st, 2016, the INNOPATHs research project kicked off, and the three of us embarked on the journey of developing a framework for analysis, a systematic review of the literature and the Decarbonisation Policy Evaluation Tool (DPET). And what a journey it was!

By May 2017, at the first meeting of INNOPATHS held in Venice, we had already started to gather input from stakeholders in different European countries, e.g. Belgium, Italy, Germany, Greece and the UK, among others, as well as in other countries around the world. We had also started to work on generating a framework for the systematic review of the literature on the impact of different environmental and energy policy instruments. These were the very first steps in a (long!) iterative process of co-design and refinement which engaged us over the following years. Every decision we had to make revealed itself more challenging that what we had envisioned. Even something as “simple” as the definition of a typology of decarbonisation policy instruments to be included in the analysis involved several rounds of iterations and questioning. One of the initial challenges was to converge to a typology of policy instruments that would, of course, build on existing research, while being accessible and understandable to both academics and policy makers. It was even harder to settle on the set of policy outcomes to analyse first, since they needed to be both policy-relevant and investigated in the academic literature. And then came the realization that we even had to account for the fact that the literature in our systematic review is really diverse in terms of methods, metrics and outcomes studied, as well as temporal and geographical contexts. Overall, a year into this task we were all feeling as if we were kept on endlessly discussing about every single detail, and the task started to look more and more daunting. One of the several meetings in which we discussed our progress with other partners and stakeholder was held in Athens; one day, we decided to get a very early start and hike to the Parthenon, hoping to be inspired by Athena, goddess of wisdom!.

And now here we are, literally 4 years after this all process started. The DPET is up and running, contains the systematic review of 211 peer-reviewed articles and high-level reports, and can be easily accessed by anyone interested in exploring its content. While the systematic review we carried out could be fruitfully extended both in terms of policy instruments and temporal and geographical scope, the DPET represents a systematic framework that can be applied by others interested in this type of evaluations and assessments. This is important since the available academic and non-academic evidence is growing fast. Furthermore, the recent COVID-19 pandemic has increased the challenge of addressing climate-related concerns in a swift manner. Our article uses the evidence in the DPET to explore whether we can pursue decarbonisation while also effectively promoting other important societal goals.

This is tantamount to asking: can we have the cake and eat it too? In our analyses, we argue that we can, but only under certain conditions. We show in a consistent fashion that some policy instrument types were able to advance some societal goals (e.g., environmental and technological), but that in some cases they had some negative impacts on others (i.e. distributional and competitiveness). There is no one-size-fits-all solution or policy instruments; but in some cases, policy design can reduce of the trade-offs. Importantly, the DPET offers a systematic mapping not only of the things we know, but also of the most important under-researched instruments, times or geographies. This, we hope, may provide inspirations to others.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Climate Change

A monthly journal dedicated to publishing the most significant and cutting-edge research on the nature, underlying causes or impacts of global climate change and its implications for the economy, policy and the world at large.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in