Cities are vital for continued climate action – early engagement and co-benefits strengthen cities’ climate commitments

Published in Social Sciences and Earth & Environment

Motivation for our study

Cities are vital actors in climate action, yet crises can challenge their capacity to lead. The COVID-19 pandemic was a global shock that impacted practically everyone, everywhere. Cities underwent visible changes, with commercial buildings emptying out, people leaving for less densely-populated areas, automotive and air traffic drastically decreasing and work from home setups becoming a norm. In many cities, these changes led to ‘positive’ impacts, such as reduced air pollution, increased wildlife and biodiversity1, and more time to ‘do creative things’2. At the same time, there were devastating amounts of deaths, job losses, and increased economic inequality3.

Given these different effects of COVID-19, we asked whether the pandemic would ultimately enhance or inhibit cities' climate commitments and actions. This question led us to conduct our new study in Nature Cities, which uses global data from the CDP to assess how COVID-19, a global health crisis, impacted cities’ reported climate actions and commitments, and the factors moderating these impacts. This study is particularly relevant for its global scale, as most studies on local climate action are limited in geographic scope and do not address the consistency of local climate action and policy through crises, but rather focus on the adoption of policies (e.g. Yeganeh et al. 2020)4. In the coming years and decades, we are more than likely to face increasing climate change disasters along with other global issues that will also inevitably impact climate change. Understanding how cities can both continue and increase their climate actions is key to realized continued commitment on a local level across developed and developing countries.

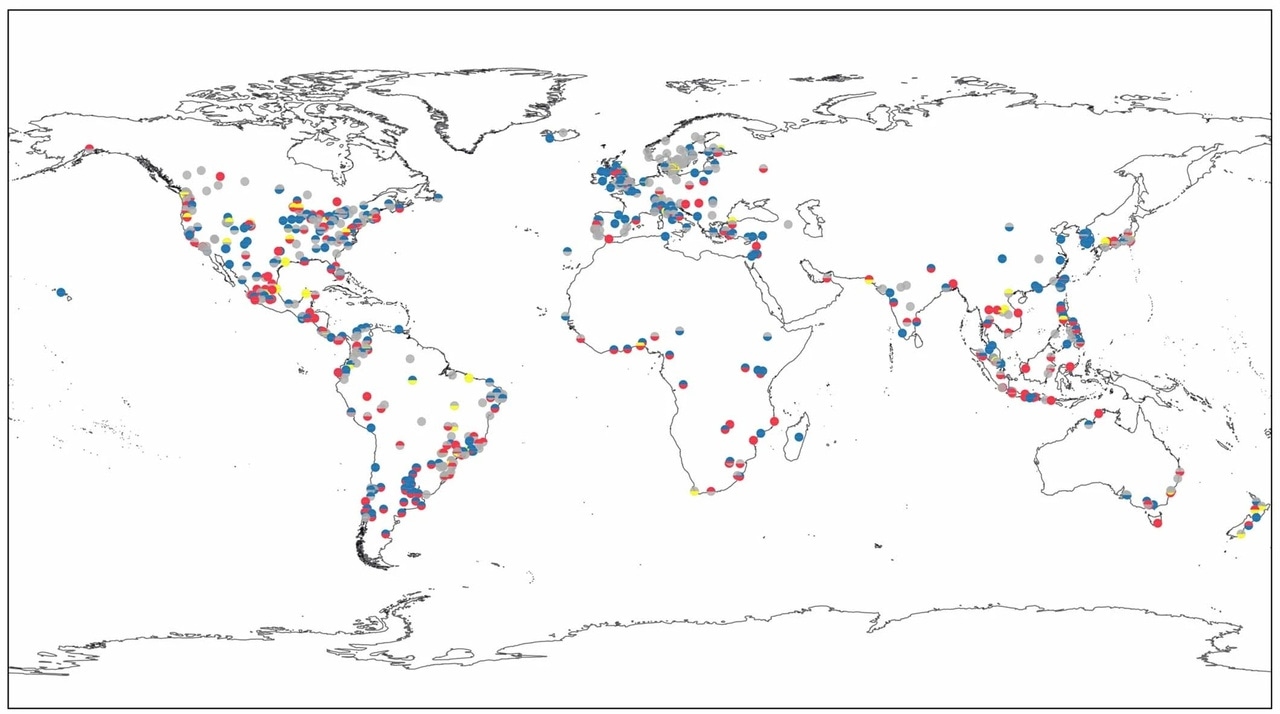

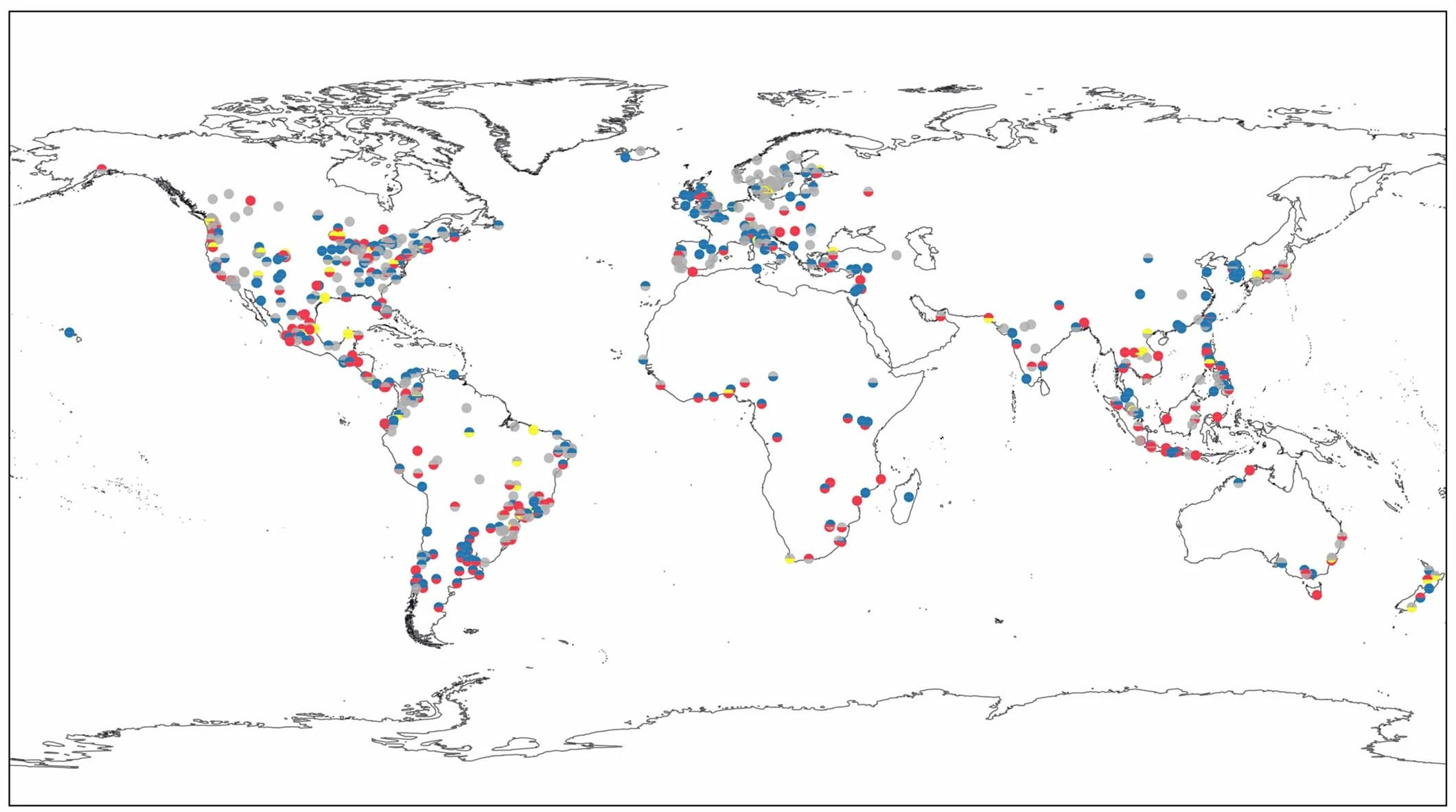

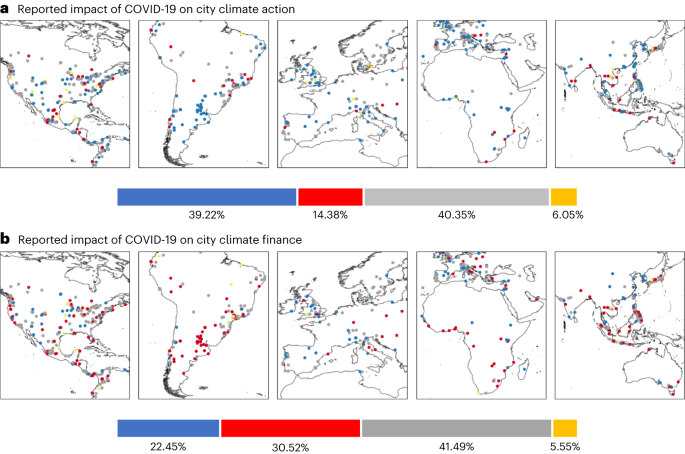

In pursuit of these insights, we relied on self-reported CDP city data5 for 793 global cities to analyze how these cities responded to COVID-19 in terms of their emphasis on climate action, climate finance availability, and synergies between COVID-19 recovery interventions and climate action (which we refer to as “green recovery” interventions). We also used other data from the CDP, socioeconomic and geospatial data to identify the factors that have significant associations with city responses to these questions (increased, decreased/reduced, ‘no change’ or ‘other’).

Key findings

- Globally, cities maintained short-term climate commitments during COVID-19 even with financing challenges, and many cities in the Global South (in Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America) reported increased climate action with no parallel increases in finance.

- Cities in the Global South take the lead on green recovery interventions, suggesting longer-term ambition on climate, while cities in Europe and North America show less ambition in green recovery measures.

- Cities that have joined climate networks, identified more climate-related health issues, opportunities from addressing climate change, and indicated collaborations with businesses on sustainability projects were more likely to maintain consistent climate actions during COVID-19, and to implement more green recovery measures – highlighting the role of co-benefits in resilient climate action during crisis.

- Cities located in countries with greater government response to COVID-19 and higher measures of liberal democracy are associated with more durable climate action, while those located in countries with higher national GDP are surprisingly less likely to have increased their emphasis on climate action and increased finance.

City data challenges

A major challenge in our study was the collection of data for cities on a global scale.

City-level data, especially from developing countries, is seriously lacking. For example, questionnaires are currently the main data collection approach used to identify actions, policies and emissions at the city level (e.g. ICLEI-CDP data used in our study). When available, the data is often incomplete, either longitudinally or geographically, which makes it difficult to compare and generate conclusions about trends. Additionally, variables may not be measured using the same criteria, and the “local” boundary may range from town, city, municipality, etc. across geographic regions. This is not surprising, as projects or studies that capture city-level data likely focus on particular regions due to specific project goals, limited financing for data collection, or difficulty of methodologies.

On the other hand, collection of geospatial data on climate-related issues, such as global temperatures, precipitation, emissions from point sources, forest fires, and droughts has seen vast improvements, with technologies for tracking via space satellites, aircrafts, and instruments on the ground. Consistent city-level geospatial data however remains limited, and requires extensive preparation for final use. Despite the promises of geospatial data (with machine learning and AI), global socioeconomic and environmental data that requires more subjectivity and on-the-ground collection will continue to rely on questionnaires.

There were several other local-level variables we would have liked to include in our analyses (e.g. data on city budgets, manufacturing, local/municipal debt, public support for climate/environmental policies, and social/political/economic/cultural values). Such data might be available on a local or regional level for select geographic regions, but not on a global scale. Some examples of such data might be:

- Federal Reserve longitudinal dataset for household debt by county in the US6.

- Yale dataset on public opinions regarding climate policies for US counties (2023 only)7.

- Yale University’s 2015 Local Governance Performance Index (LGPI) pilot studies in Tunisia8.

Through working on this study, we realized that there is an urgent need for standardized city and local-level, longitudinal data at the global level that can be used for global climate action and policy studies. Creating an accessible data format for the city questionnaire from year to year should be on the top of the agenda for the city climate data community, in order to lower barriers to longitudinal data analysis. Increased partnerships between programs and institutions across global regions could allow for local researchers to undertake research based on local perspectives and approaches to research, while providing a common framework for standardization of methodologies. In these cases, governance capacity will play a vital role in being able to undertake such data collection, and manage and maintain publicly accessible databases.

To conclude, cities can sustain climate action, especially by leveraging health and environmental co-benefits, and collaborating on sustainability initiatives with climate networks and businesses. However, access to more and better data will be needed to support their efforts over time, which may call for large research budgets and standardized reporting through global organizations, such as the World Bank.

Thank you to my wonderful co-authors – Tanya O’Garra, Andrew Deneault, Christopher Orr and Sander Chan – for their hard work and commitment to meaningful climate action research.

References

- “Global Study Finds While Humans Sheltered in Place, Wildlife Roamed.” University of Montana. www.umt.edu/news/2023/07/071023hebb.php#:~:text=In%20locations%20with%20strict%20lockdown,they%20were%20before%20the%20pandemic (2023)

- O’Garra, Tanya, and Fouquet, Roger. Willingness to reduce travel consumption to support a low-carbon transition beyond COVID-19. Ecological Economics vol. 193 107297 at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107297 (2022)

- World Bank. World Development Report 2022 : Finance for an Equitable Recovery (English). World development indicators,World development report Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/408661644986413472/World-Development-Report-2022-Finance-for-an-Equitable-Recovery

- Yeganeh, A. J., McCoy, A. P. & Schenk, T. Determinants of climate change policy adoption: A meta-analysis. Urban Climate vol. 31 100547 at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2019.100547 (2020)

- CDP. CDP Cities, States & Regions Open Data Portal | CDP Open Data Portal. at https://data.cdp.net/ (2022)

- See https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/dataviz/household_debt/county/map/#state:all;year:2023

- See https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us/

- See https://gld.gu.se/media/1107/lgpi-report-eng.pdf

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Cities

This journal aims to deepen and integrate basic and applied understanding of the character and dynamics of cities, including their roles, impacts and influences — past, present and future.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in