City Life Still Charms and Pandemics and Remote Work Won't Change That

Published in Social Sciences, Earth & Environment, and Arts & Humanities

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, it seemed like the world as we knew it was turning upside down. Cities, the bustling hubs of connectivity and culture, were hit hard. The virus spread rapidly through these dense urban landscapes, and the death toll in cities soared. This led to a wave of speculation: Was this the end of city living as we know it?

Reports started to emerge of people fleeing cities for the suburbs or even rural areas, looking for more space and safety. In countries around the globe, from Australia to the United States, real estate markets saw a shift. People were leaving the cities, and the pandemic was reshaping migration patterns.

The reasons for this potential exodus were many. Cities were infection hotspots. Public spaces felt risky. Schools closed their doors, businesses shut down, and the perks of city life seemed to vanish overnight. Social distancing became the norm, and remote work transformed how we lived and worked. Suddenly, the daily commute was a thing of the past, and the need for a home office became essential. The cost of city living, already high, now had to be weighed against these new realities.

But was this change in attitude towards city living going to last? That's what our study aimed to find out, focusing on Tokyo, one of the world's most iconic metropolises. We set up an experiment to see if people's preferences for where they lived had shifted because of the pandemic. We created different scenarios, including the possibility of another pandemic and the option to work from home, to see how they would affect people's choices.

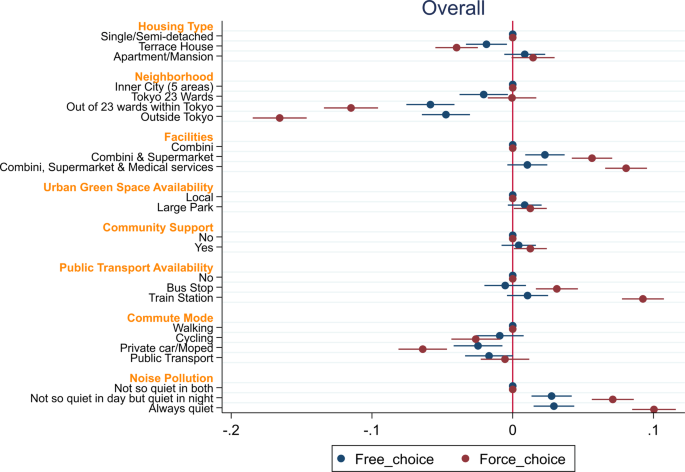

What we found was interesting. Despite the challenges, Tokyo hadn't lost its appeal. Even with reminders of the pandemic and the option to telecommute, people still wanted to live in the city. We looked at different areas within Tokyo and found that, generally, the thought of another pandemic didn't change people's preferences much. However, when we combined the remote work scenario with the pandemic reminder, we saw an increase in the likelihood of people wanting to move.

Interestingly, those who could work from home didn't want to move out of Tokyo. They were indifferent to living in the inner city or the surrounding 23 wards. Our study showed that people reminded of the pandemic tended to dislike living outside the central wards but preferred quieter environments. This was also true when we combined remote work with the pandemic scenario, although the dislike for living outside the central wards was less pronounced.

We found that income played a role in these preferences. Higher-income individuals were less likely to move out of Tokyo if they could work remotely. Also, younger people, especially those aged 20-29, didn't want to live outside the inner wards and valued amenities and community support. However, those who experienced a decline in mental well-being were more open to moving away from the city center and were concerned about noise pollution.

These findings suggest that while the pandemic has brought changes, it's unlikely to cause a massive shift in urban living, at least in Tokyo. Younger people, in particular, seem reluctant to leave. This is good news for those worried about unsustainable urban growth patterns. Compact urban development, which offers many benefits for sustainability and resilience, still seems to be the way forward. However, the pandemic has shown that we need to design our cities carefully to balance the need for compact living with the potential downsides.

In conclusion, our study indicates that while the pandemic may lead to neighborhood and district-level changes, it is unlikely to alter urban population dynamics on larger scales significantly. We suggest that the city's allure remains strong, and the future of urban living, particularly in Tokyo, looks promising. As we move forward, it's crucial to keep analyzing population data and understanding real-world behaviors to plan cities that are not only resilient but also places where people want to live.

Follow the Topic

-

npj Urban Sustainability

An open access, online-only journal for urban scientists, policy makers and practitioners interested in understanding and managing urbanization processes.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Urban Nature-Based Solutions and Water

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Sep 23, 2026

Radical Civic Practices: The Future of Urban Environmental Justice Studies in a Highly Unequal World

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 10, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in