Climate Shapes India's Savanna-Forest Stability, but Human Actions Can Make the Difference

Published in Earth & Environment and Sustainability

Background

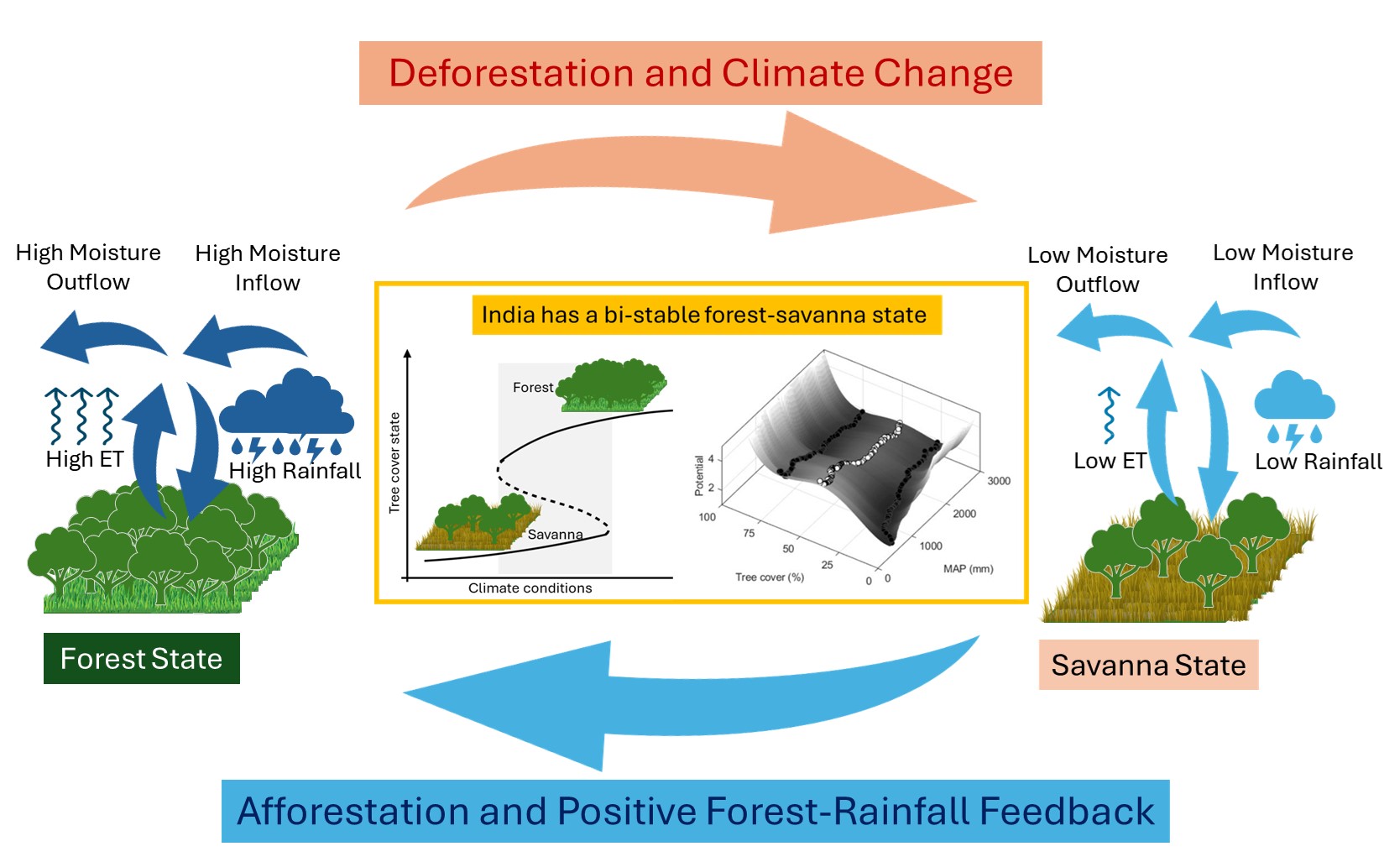

India's hydroclimate is substantially influenced by the Indian summer monsoon, which determines the majority of the country's water availability. However, rainfall is not just about how much it rains, but when and how consistently it rains. These characteristics also matter for vegetation and thus determine the distribution of tree cover. Forests with dense tree cover need a relatively steady moisture supply. In contrast, savannas – grassy systems with scattered trees and relatively open canopies – can deal better with strong swings between wet and dry years. Given climate change and global warming, a natural question arises: how will the changing climate impact India's forests and savannas? However, at the same time, India is pushing hard on greening through afforestation, forest conservation laws, and restoration programs. Thus, given both the shifting climate and India's ambitious forest conservation policies, which are reshaping the balance between forest and savanna, we aim to quantify the contributions of climate to India's tree cover, separate non-climate-driven tree cover changes, and project what the picture would look like at the end of the century.

The picture is from Tadoba National Park in India. This tiger reserve primarily comprises dense teak and bamboo forests, as well as vast patches of open grasslands.

What was done?

Satellite-derived datasets provide gridded data for estimates of the fraction of land covered by trees. We link these patterns to climate using statistical models and dynamical systems theory to map where forests and savannas are stable, where they can coexist under the same climate, and how easily one state can tip into the other. This approach enables us to distinguish between places where climate alone explains tree cover and places where human actions or ecological processes must also be playing a substantial role. That distinction is crucial for understanding where policy can still meaningfully shift landscapes toward more or less tree cover.

How has existing tree cover changed in the past two decades?

Between 2001 and 2020, the share of India's land with any tree cover decreased slightly. However, within the tree-covered areas, low-cover grids decreased. In contrast, both savanna-like and forest-like grids increased, particularly in the Himalayas, central and eastern India, and parts of peninsular India. Model results show that recent gains in the likelihood of forest cannot be explained by climate alone. Instead, they point to other drivers, such as forest protection, natural regeneration, and processes like the fertilizing effect of rising CO2 on tree growth, which might push some landscapes toward denser tree cover.

A schematic of the bistability of India's tree cover.

Forests, savannas, and bistability

A key insight is that in many parts of India, the same rainfall level can support either a forest or a savanna. In these regions, both states are stable options for the land, separated by an unstable middle zone of intermediate tree cover. Where rainfall is modest and more variable, the savanna state tends to be more stable and less prone to shifting to another state. Where rainfall is less variable, the forest becomes more stable. The presence of two stable tree-cover states under the same climate means that land management decisions may have strong implications. In bistable regions, policies that protect and expand forests can lead to higher tree cover, whereas deforestation, tree mortality, and fire can result in a low-cover savanna state.

What does this mean for the future?

We found that by the end of the century, due to climate change, rainfall will become more variable in many places in India, even though the total amount of rainfall may remain unchanged. This change promotes a landscape with more savanna-like vegetation than forests.

However, given that India's tree cover has undergone substantial non-climate-driven changes over the past two decades, India's future tree cover will depend not only on rainfall but also on how proactively people manage their land. The findings underscore that smart policy and restoration efforts can still have a meaningful influence on whether large parts of India transition toward forests, savannas, or remain near critical tipping points between the two.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in