Clues to Cacao

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Our paper 'The use and domestication of Theobroma cacao during the mid-Holocene in the upper Amazon' can be found here.

Francisco Valdez does not believe in coincidences.

In the fall of 2008 I was investigating ancient agriculture in Ecuador for my doctoral research and found out about Valdez’s work at the Santa-Ana La Florida (SALF) site and the early dates associated with it. I met him In Quito and he graciously showed me some of the artefacts recovered from the site, including the earliest ceramic stirrup spout bottles yet found anywhere in the Americas. I was stunned by their beauty and sophistication. We made plans to meet up again, so I could sample residues from the artefacts and in 2009 I was able to visit SALF, participate in some excavation, and collect comparative plants from around the site.

In 2010 I presented the preliminary results at a conference and Michael Blake, whom I knew previously, was there. We sat down to chat about my talk and he commented that the stirrup spout bottles recovered from SALF reminded him of ancient spouted vessels from Mexico and Central America – vessels that were known to have been used in the preparation of cacao drinks. Had I ever thought of looking for starch grains of Theobroma cacao in addition to the other microscopic plant residues I was looking for? It’s hard to describe how the brain synapses were firing in all directions at this point – we both knew that for the past 10 years or so, molecular geneticists, including Claire Lanaud and others, were pointing to the upper Amazon, where SALF is located, as the homeland of domesticated cacao. Yet because beverages made from cacao are so iconic of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures—and in fact the words “cacao” and “chocolate” are derived from Maya words for this food—many researchers have long supported the idea that cacao was first domesticated in Mesoamerica. So, we have two competing theories: 1) that a wild Theobroma species was transported to and then domesticated in Central America and/or Mexico; or that 2) cacao was first domesticated in the upper Amazon region and was dispersed from there. In fact, the latter hypothesis is not an entirely new idea, as plant geographers had previously proposed this in the early half of the 20th century due to the high diversity of Theobroma in this region and genetic studies have more recently supported this as well: that the geographic centre of a plant's genetic diversity is usually where its origin lies. Might it be possible that Francisco Valdez and his team’s archaeological discoveries at SALF might help to shed new light on cacao’s origin?

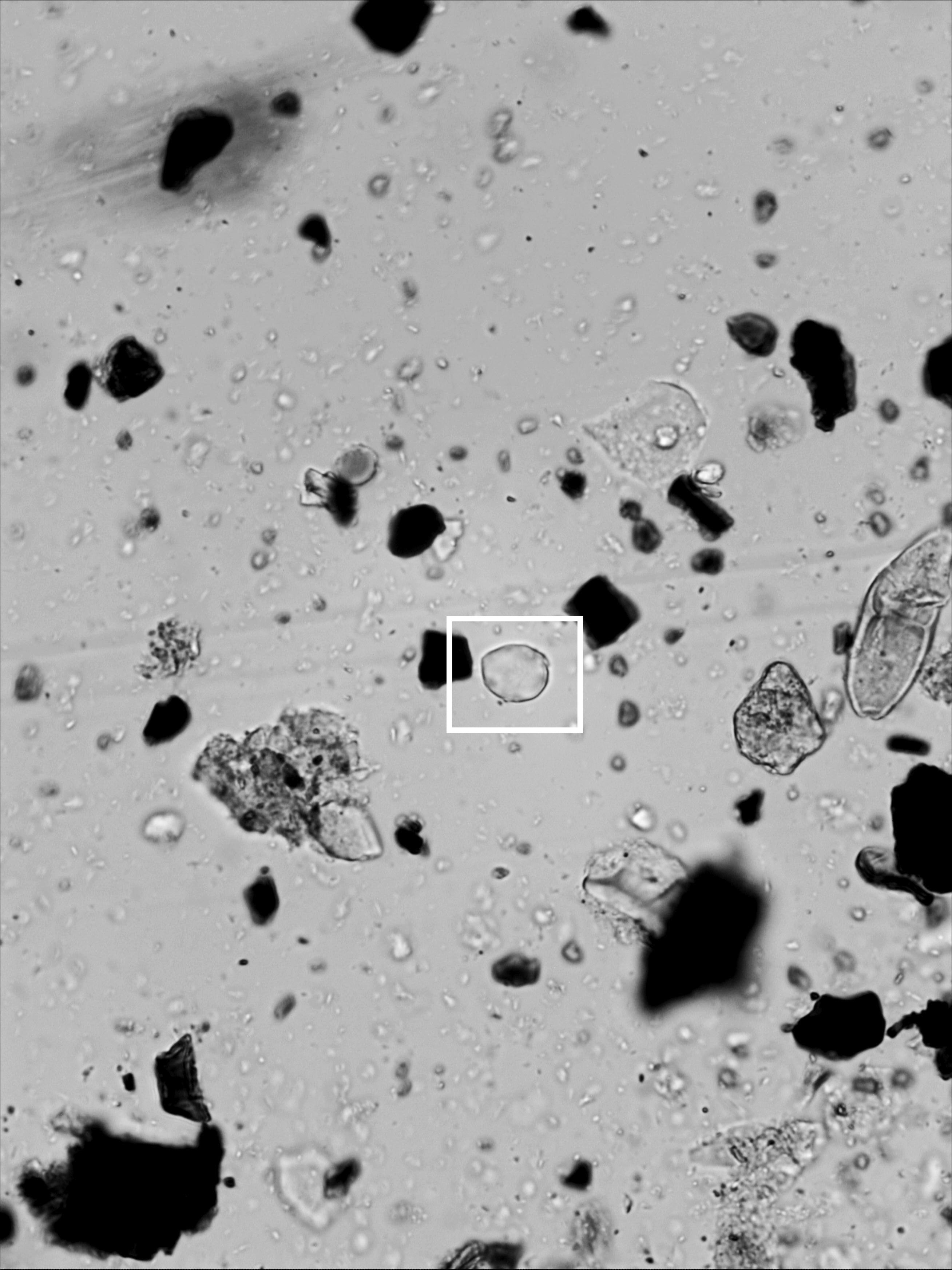

In answer to Michael’s original question, had I looked at starch grains of Theobroma cacao?, the answer was “yes.” I already knew that they were present in small quantities in cacao seeds and were very tiny (even smaller than the microscopic starch grains of many other common plant species that we look for in archaeological sites), but I also knew from my preliminary results that I had many small unidentified starch grains present in SALF’s artefacts’ residues. I needed to take a closer look! Every pun intended.

Once I had identified possible diagnostic forms of Theobroma starch grains in the residues, my next step was to greatly expand my comparative collection to determine if these forms were unique to Theobroma or found in other related species.

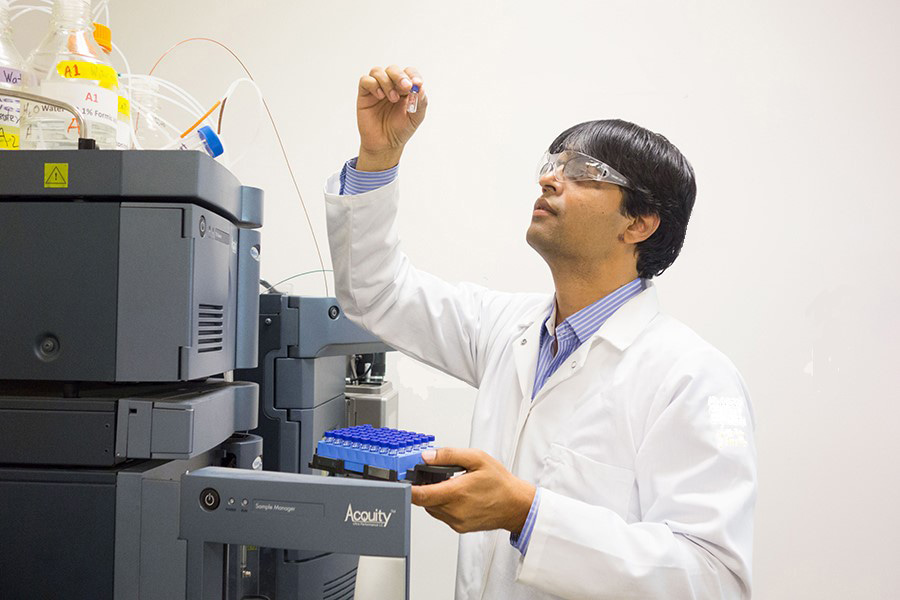

By 2011-2013, my analyses confirmed that starch grains diagnostic for Theobroma could be distinguished from those of other plants and were present in artefact residues from SALF. Blake had already contacted his colleague, Terry Powis, who had long-since been involved in cacao research in Mesoamerica, and Terry was already working with Nilesh Gaikwad on developing stringent sampling methods to refine mass-spectrometry methods for identifying the key active compounds that make chocolate so delicious: caffeine, theobromine, and theophylline. They and their colleagues had been working to refine the methods of identifying minute traces of these compounds in ancient artefact residues in Mesoamerica. In fact, just a few years earlier, they had helped to identify cacao residues on pottery from the 3800 year-old settlement of Paso de la Amada, located on the Pacific coast of Chiapas, Mexico.

Our next step was to secure funding to test the SALF collection for the chemical residues that are unique to cacao and send Terry and his colleague Patrick Severts to Quito to sample the SALF artefacts.

Meanwhile, Francisco Valdez was working with Claire Lanaud. Claire's research team from CIRAD, and Rey Gaston Loor Solorzano's team from INIAP (Ecuador), were working on the domestication of the Nacional cacao variety from Ecuador, on the origin of the production of "fine" and "flavor" cacao in Ecuador. Despite its cultivation on the Pacific coast of Ecuador, they identified its origin in the southern region of the Ecuadorian Amazon (Zamora Chinchipe province where the SALF site is located), and then returned to this region to collect new native genetic resources suitable to improve new aromatic cacao varieties. During their expedition in 2010, they heard about an archaeologist who was working in this region 50 km from Nuevo Paraiso where they were collecting native cacao trees. Shortly after, back in Montpellier, Claire found information on the SALF archaeological site, and immediately contacted Francisco Valdez to propose analyses to recover ancient DNA in the residues of the artefacts from SALF, in the hopes of detecting ancient cacao DNA.

Later, Claire and Gaston's teams collected native cacao trees close to the SALF site and Francisco also participated - with this furthering to reinforce the collaboration between archaeologists and biologists.

Claire subsequently sampled SALF artefacts for ancient DNA, and I shared additional residue samples I collected with both Nilesh and Claire.

Working in his lab at UC Davis, Nilesh Gaikwad had recorded positive results for cacao’s diagnostic compound theobromine in the residues recovered from many of the artefacts from SALF. Meanwhile in Montpellier, France, Claire and her DNA team were adapting and refining methods to recover ancient DNA from a variety of residue types and were able to identify and distinguish the small strands of DNA from other plant species – showing that wild species of Theobroma, domesticated T. cacao, and a closely-related species (Herrania) were all used at SALF. Our results showed that the people of SALF were using domesticated T. cacao by at least 5,300 years ago – almost 1500 years earlier than in Mesoamerica – and we confirmed the upper Amazon as the oldest region yet identified as the birthplace of cacao.

Francisco Valdez and his team, from the outset of investigations, involved the local community in the archaeological excavations and in the restoration of some of the architectural features at the site – especially because of their expertise in traditional stone and daub construction techniques. Importantly, a local women’s association also worked on building and maintaining a community nursery for cacao sprouts, and the saplings were later planted in their own agricultural fields.

It is only through the endurance of these local traditional practices and knowledges that we are much better informed, while the local community recovers the tangible and intangible remnants of their history, reaffirms their descendant ancestral connections, and are now the rightful caretakers of SALF and its Interpretive Centre.

Our search for cacao at SALF took 10 years – from start to publication – and required the time, expertise, coordination, and patience, of many people (most of whom have not met face-to-face) spread over four countries and three continents. While that may seem like a long time, this story lay hidden – in the mists of the upper Amazon cloud forest – for more than 5000 years to be told by a group of researchers and local community members that, whether through serendipity or by a calling of the “food of the gods,” came together and followed the clues -- but Francisco Valdez firmly believes that “there are no coincidences in life.”

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Ecology & Evolution

This journal is interested in the full spectrum of ecological and evolutionary biology, encompassing approaches at the molecular, organismal, population, community and ecosystem levels, as well as relevant parts of the social sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning of global peatlands

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jul 27, 2026

Understanding species redistributions under global climate change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Wow - what a story! I am especially impressed by your engagement with the local community - was this always part of the planned project or did it evolve over time?

Thank you Ben. As archaeologists, we have an ethical obligation to engage with the local community, especially when there is a descendant population to the archaeological culture we are studying. Of course, this is not always followed, and varies in different parts of the world. The level of community engagement and the types of involvement is ultimately determined by the community itself - and we follow their lead by providing the opportunities and, as best as possible, the funding to do so. We only scratched the surface in this article on the activities and programs that Francisco and his team were involved in - we consider the local community to be instrumental in our work.