Collectivism Helped During Covid - Except for This

Published in Social Sciences, General & Internal Medicine, and Agricultural & Food Science

Collectivistic cultures tended to do better during the Covid pandemic. Studies have documented how the strong social norms of collectivistic culture is associated with more mask use, narrower social networks that limited the spread, and more adherence to public health policies. But there was at least one situation where collectivistic cultures fared worse.

Covid-19 struck first in China, and the timing just so happened to be around the Chinese New Year holiday. The holiday is a time when millions of people visit family and friends. The practice is so entrenched there's a specific verb for it--bainian, "pay a New Year call."

Ambiguous Virus Risk, Clear Social Risk

Chinese New Year fell in the ambiguous early days of the pandemic. People were still figuring out whether this new virus was serious or not. Was it just the flu? Did it really spread from human to human?

That ambiguity meant people had to weigh the uncertain danger of the new virus against the certain social danger of offending friends and family. People who decided to stay home and skip the visits might end up regretting that decision if the virus turned out to be a dud.

Social Pressure is Not Equally Spread

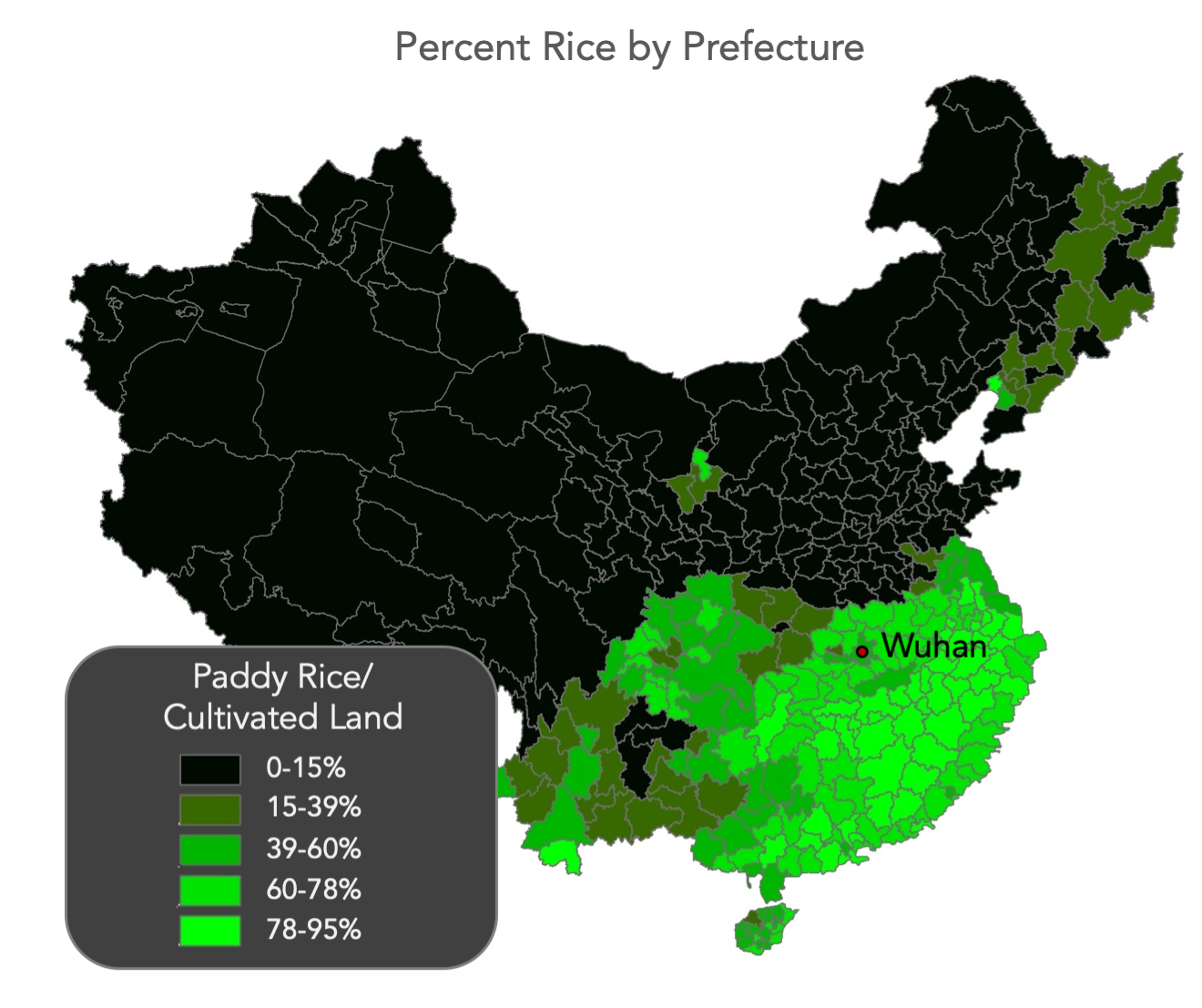

My collaborators and I thought culture might play a role in how people balance the social pressure of the holiday. To disentangle the role of culture, we leveraged that fact that southern China and northern China have different cultures. Southern China has a history of rice farming, which required more labor than the wheat farming of the north.

Paddy rice also used irrigation networks to flood the fields, and these networks meant farmers had to coordinate water use, flooding, and repairs. These farming legacies help explain why people in rice-farming cultures report more binding relationships and tighter social norms.

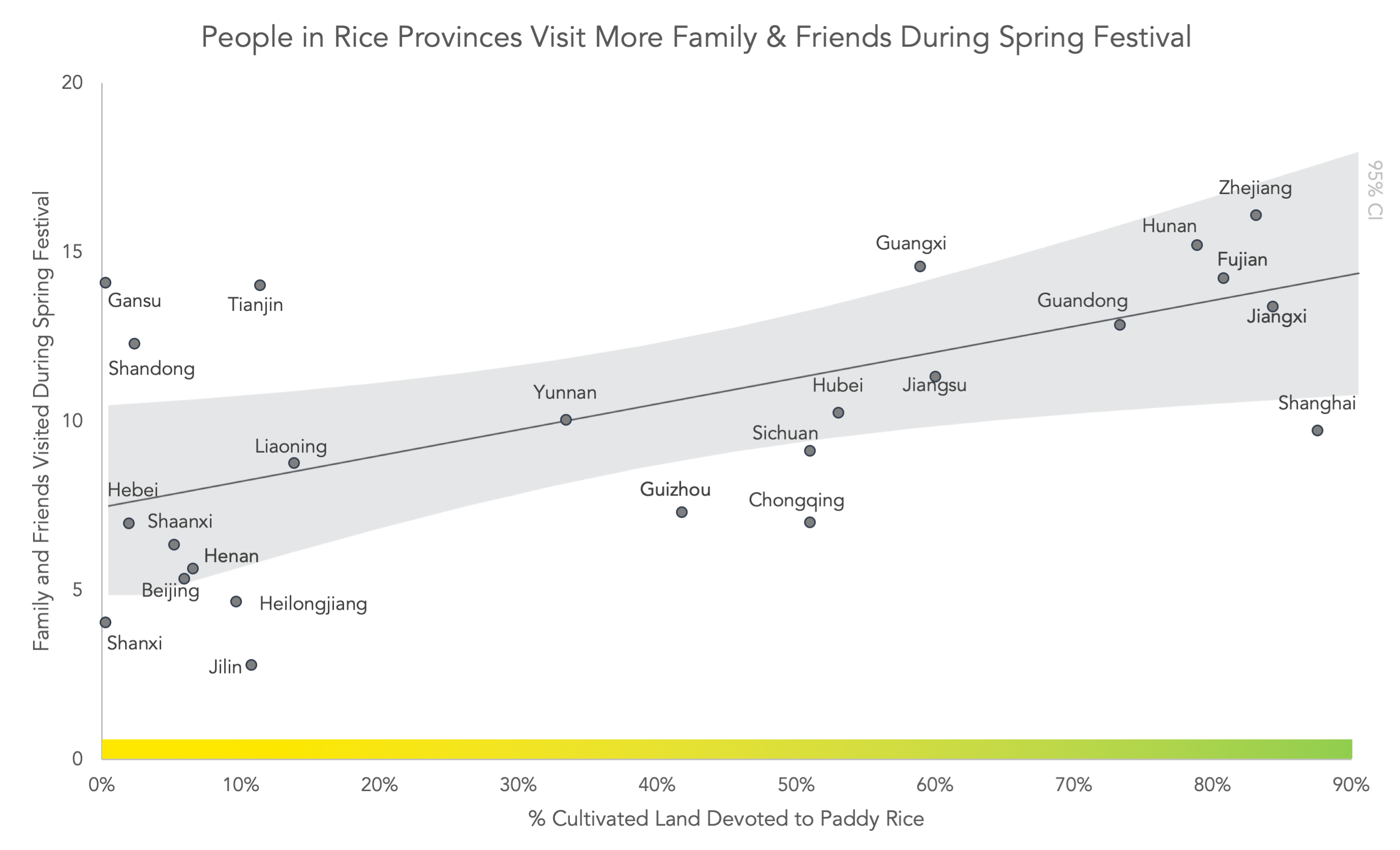

Visiting family for the holiday is one of those social norms, and people in southern China report more visits for the holiday. In a nationally representative survey of approximately 12,000 respondents from before the pandemic people in rice-farming areas reported visiting an average of around 13 households for the New Year, as opposed to about 7 households in the wheat area.

When Social Norms Backfire

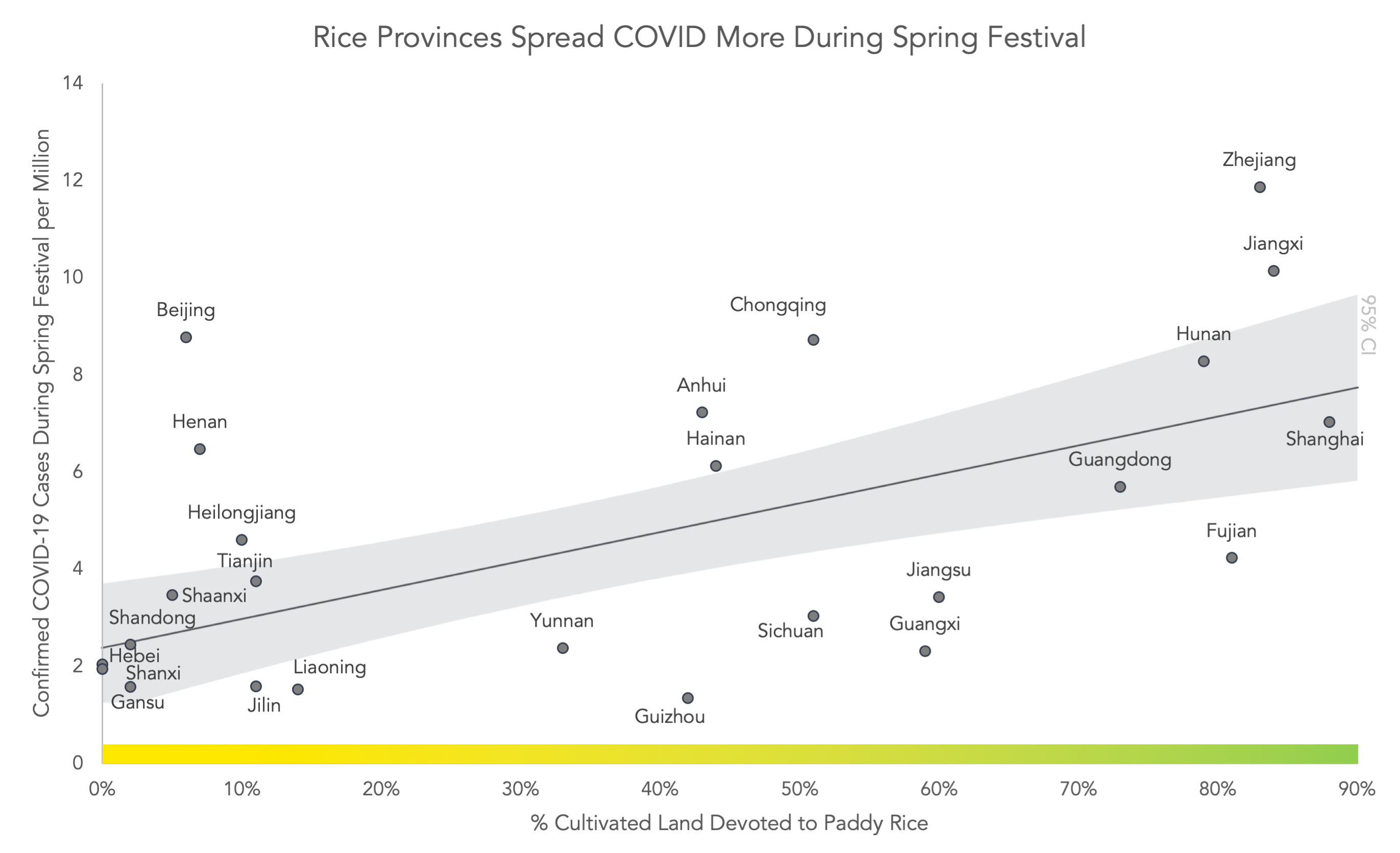

In general, strong social norms seemed to help during the pandemic. Cultures with strong norms tended to have fewer cases. But when the norm is to visit other people, that could give the virus more opportunities to spread.

And that's what we found when we analyzed coronavirus cases around the Chinese New Year holiday. Regions with a history of rice farming suffered about three times more infections than regions with a history of wheat farming.

But how do we know these are specific to the holiday? Perhaps rice areas just suffered more infections in general. For example, maybe the virus spreads more in rice-farming regions because they have a different climate.

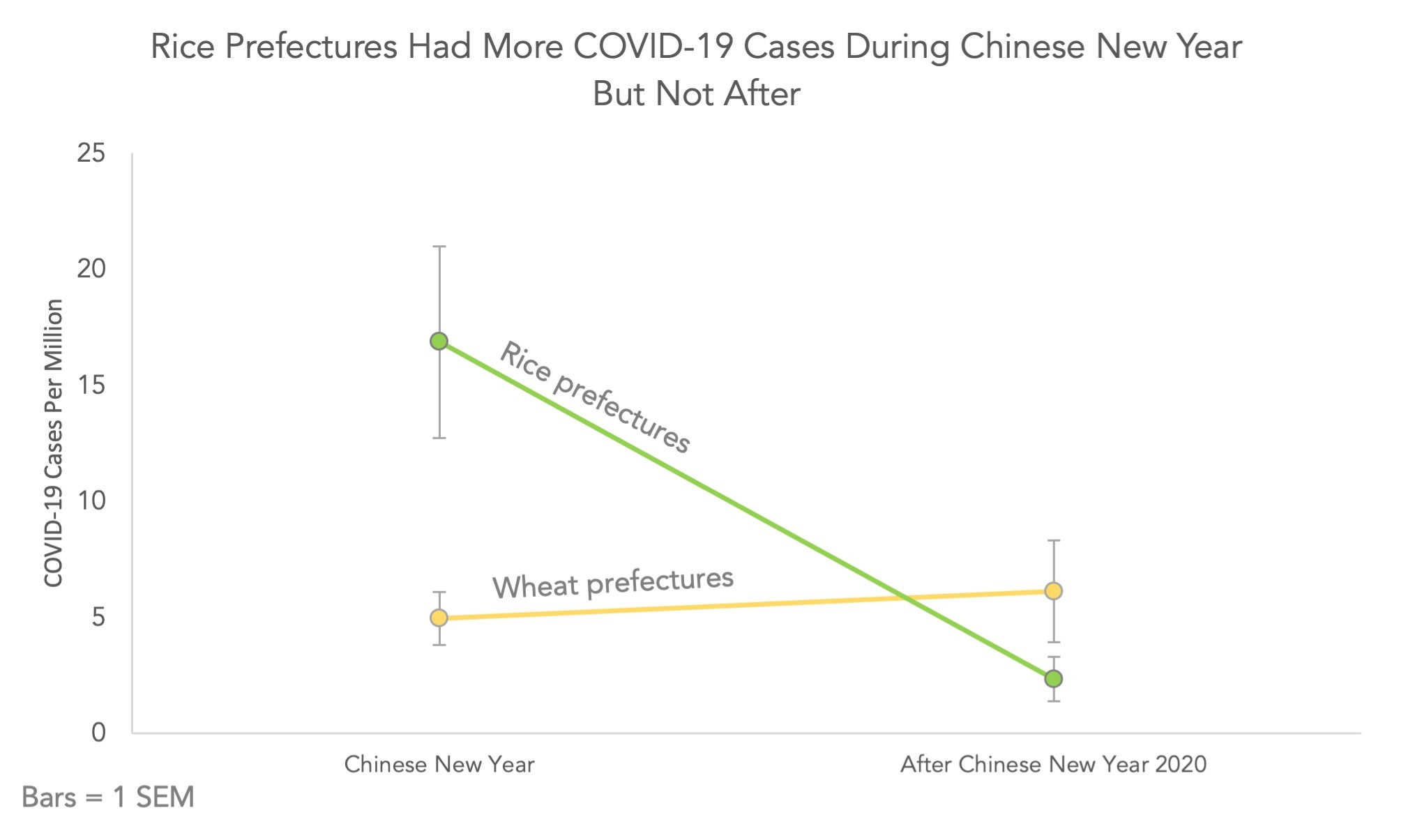

To answer that question, we compared infections in the weeks around the Chinese New Year holiday to the weeks after it. We built in a buffer to account for the incubation period of the virus. Sure enough, the difference was limited to the Chinese New Year holiday.

Changing Norms, Changing Risk

We think the key was the ambiguous risk early in the pandemic. At that time, the norms around the virus weren't clear. That meant there was a conflict between the norm to visit family and the emerging norms for social distancing.

But when Chinese New Year came around the next year, the danger was clear. There was no longer any ambiguity about what the social norm was. In that case, people in rice-farming areas stayed home.

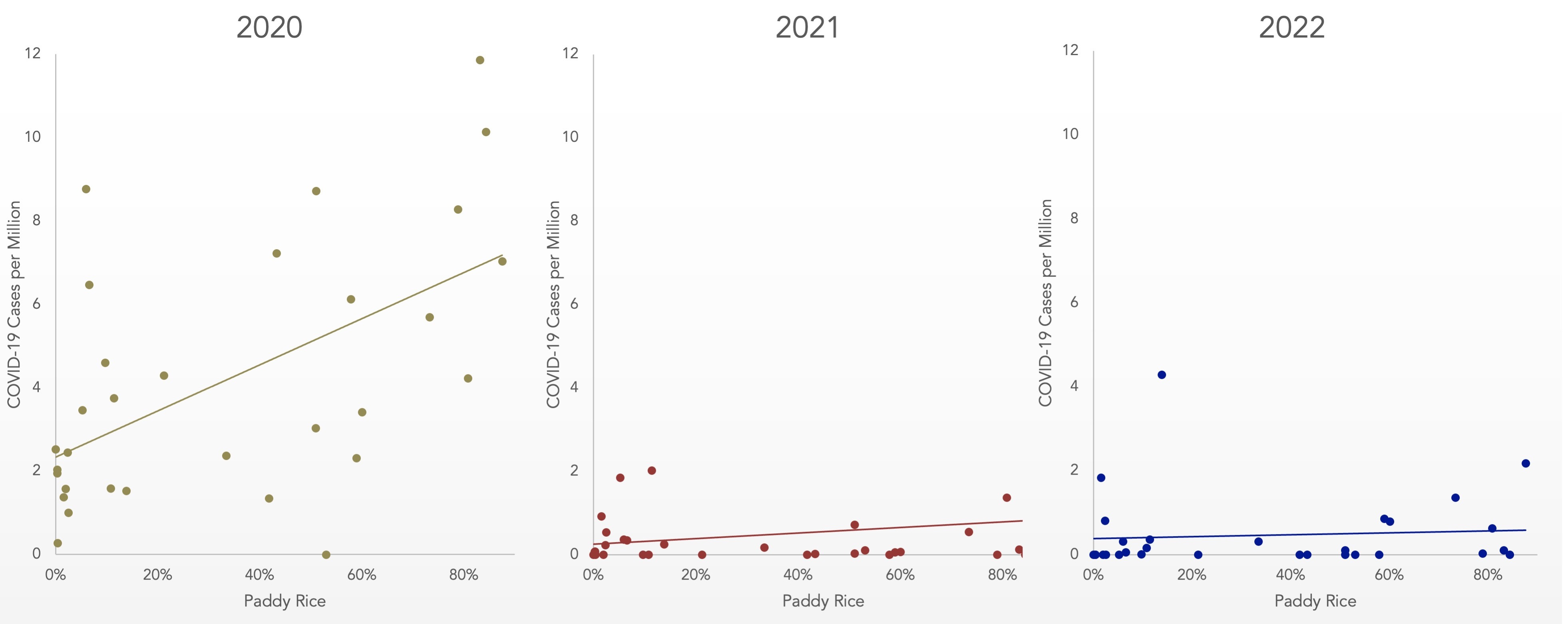

When we analyzed Chinese New Year infections in 2021 and 2022, we found no relationship with rice. By this point, the norms for caution and social distancing were clear enough to outweigh the norms for holiday visits.

Data like this help shed light on how virus spread depends not just on the biological characteristics of the virus but also the cultural characteristics of the humans it infects. Understanding the competing demands of safety and social ties can help us understand why cultural characteristics help sometimes and hurt other times.

This data also makes clear that cultures are not clearly good or bad, even for a particular outcome. Instead, the effect of culture can change depending on the timing.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Thanks to my co-authors Xindong Wei, Kaili Zhang, and Fengyan Wang.

The paper is available free to download on SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4569952