Computing Spectral Features of Three-Body Interactions

Published in Physics

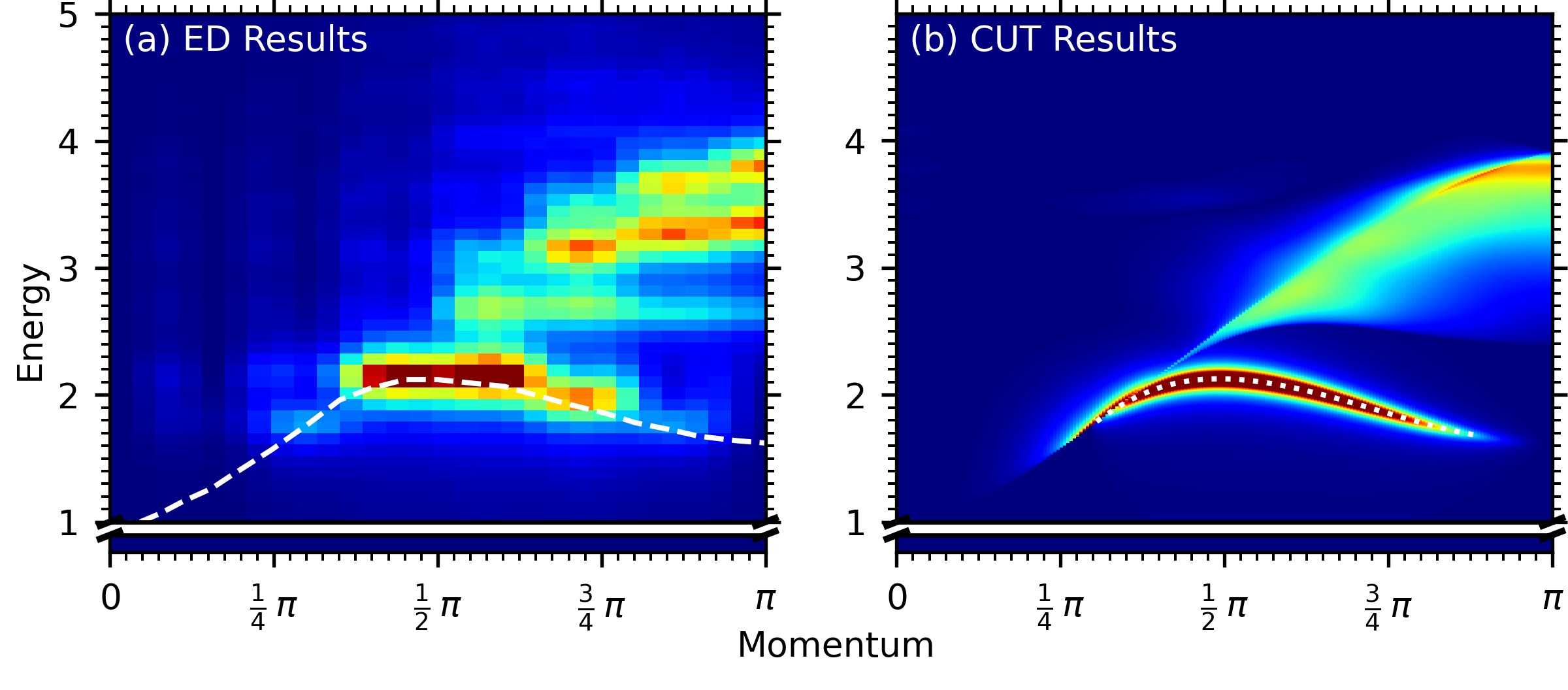

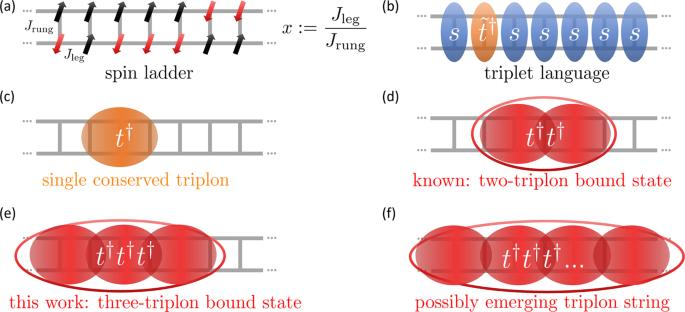

Response functions describe the response of a systems to external perturbance. They are fundamental to describing and understanding various scattering experiments theoretically. The perturbation in the system excites it from the ground (unperturbed) state to elementary excitations, which can be single- or multi-particles. To correctly interpret the experimental signals, it is important to identify how many elementary excitations are involved and whether a signal is connected to a multi-particle continuum or to bound states by comparing it with theoretical computations. However, this distinction requires one to understand what exactly an elementary excitation is in the context of a given system. The genuine elementary excitations are conserved in the system; hence, the Hamiltonian should be described in a particle-conserving basis. Note that the term “particle-conserving” is used for the conservation of excitations as well. However, the initial formulation of a condensed-matter Hamiltonian is often not particle conserving. Many state-of-the-art methods that compute response functions cannot discriminate between the number of involved excitations. One can still interpret the results by utilizing additional information, such as analytical results of bound state energies, but often the distinction remains ambiguous. One example can be found in Fig. 1, which depicts results computed using exact diagonalization. We see that the distinction between bound and continuum states is only possible by using additional information.

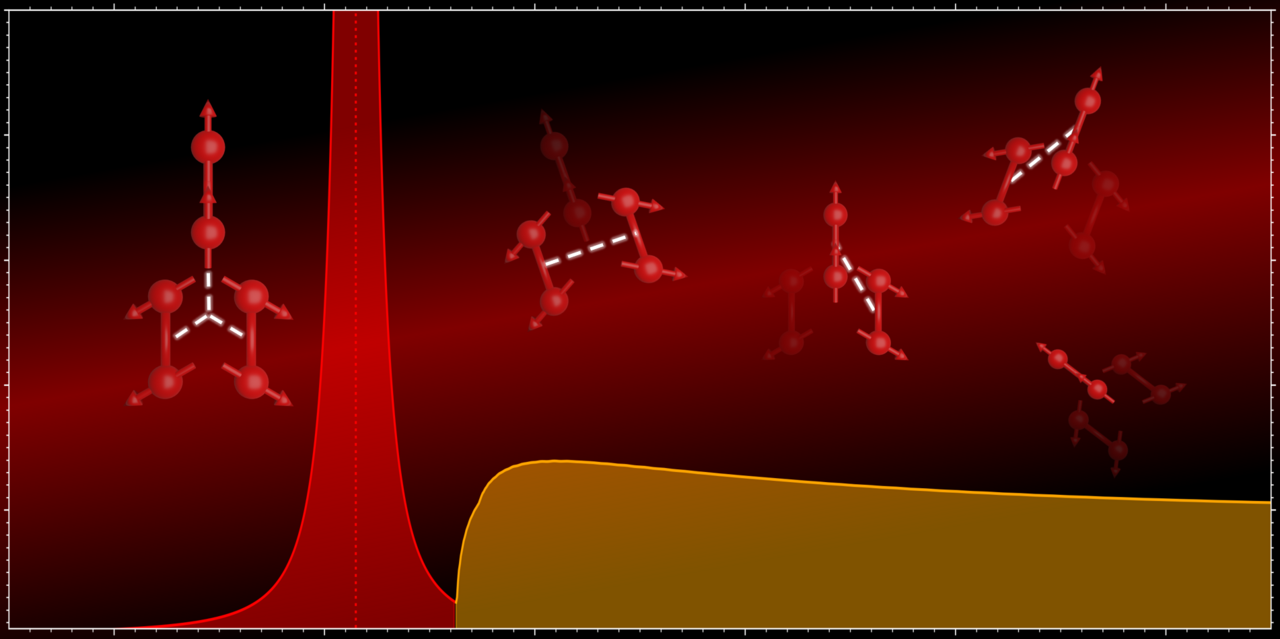

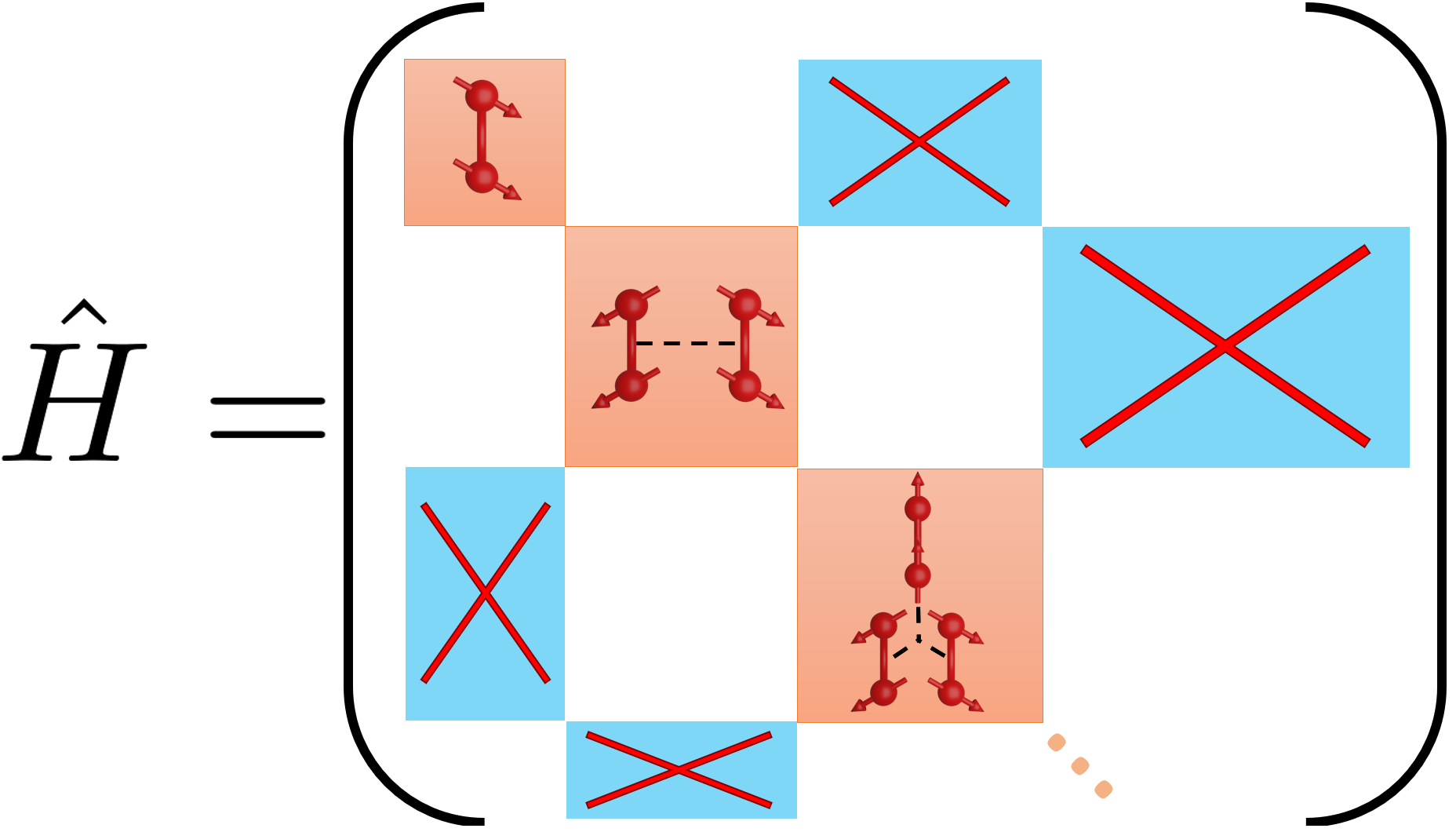

The solution to this problem is a unitary transformation of the non-particle-conserving Hamiltonian to a basis where it is particle conserving. In our computations, we achieve this with the method of continuous unitary transformations (CUTs). The key idea is to not perform the transformation in a single step, but rather to perform it continuously. To understand why this is advantageous, it helps to visualize the unitary transformation as a rotation in a high-dimensional Hilbert space (which it essentially is). By continuously applying infinitesimal rotations over the course of the full CUT, one can change the rotation axis according to the form of the Hamiltonian in the momentary basis. In the CUT framework, one chooses a generator scheme, which defines the way the rotation axis is chosen. The CUT provides a systematic and renormalizing way to find the particle-conserving basis of the Hamiltonian. Mathematically, the non-particle-conserving Hamiltonian has terms which create more excitations than they annihilate and vice versa. In the particle-conserving basis, these terms are zero and all particle-conserving terms are renormalized. This is depicted schematically in Fig. 2 for the spin ladder system, where the elementary excitations are triplons, i.e. S=1 excitations of two coupled spins 1/2, shown as two red spins connected by a red line. Details about the nature of the triplon excitations and how the CUT is performed can be found in the Supplementary Methods of our paper (see link above).

After obtaining the particle-conserving Hamiltonian, response functions can be computed by applying Lanczos tridiagonalization and a subsequent continued fraction expansion of the resolvent. The fact that the system is now described with particle conservation provides various important advantages:

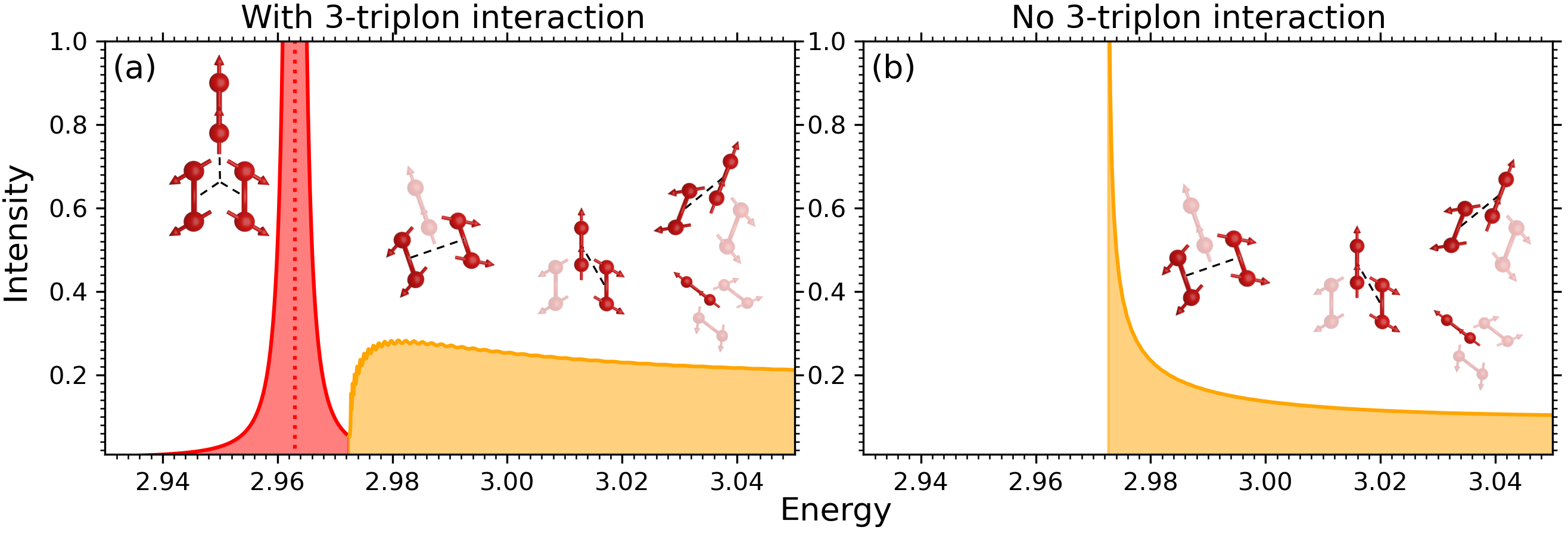

- One can calculate the response for a given number of excitations by only considering the respective decoupled Hilbert space. This reduces the computational effort and allows for an unambiguous interpretation of how many excitations contribute to which parts of the response.

- The continued fraction expansion allows for a clear distinction between continuum and bound states.

- The computed Hamiltonian is described in the thermodynamic limit. The only methodical approximation is the truncation of the least relevant terms in the CUT and the Lanczos algorithm. Therefore, the resolution in energy and momentum can be increased indefinitely for the computed response functions – you can zoom in as close as you want!

- Since the Hamiltonian is described in second quantization, its blocks are decoupled into n-body interactions: A constant ground-state energy term, a one-body energy block, a two-body interaction block, et cetera. This allows one to selectively turn off n-body interactions by simply neglecting the respective block of the Hamiltonian in the computation. Note that n-body irreducible interactions require at least n excitations to be present for the interaction to have an effect.

We applied the CUT method to compute the scattering intensity of resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) on antiferromagnetic spin ladders, relevant for cuprates. RIXS at the Cu L3-edge of cuprates is known to have a spin-conserving and non-spin-conserving channel. In the past, CUT has been applied extensively to inelastic neutron scattering, which is restricted to the non-spin-conserving channel. Details concerning the model and the observables can be found in our paper. When analyzing our computed RIXS responses in the spin-conserving channel, we found three-body bound states. Out of curiosity, we turned off all three-triplon interactions to investigate how they affect the bound state. Surprisingly, the bound state disappeared completely, implying that genuine three-body interactions are necessary for the formation of the three-body bound state, see Fig. 3. To our knowledge, this is novel behavior, since normally two-body interactions alone are responsible for forming many-bound states in nature: atoms, molecules and solid states are formed solely due to two-body interactions, i.e. the Coulomb interaction. Not so for our spin-ladder system. Indeed, the emergence of the three-body bound state in the spin ladder is a smoking gun feature of irreducible three-body interactions, which became the main message of our paper.

As is often the case in science, one can unexpectedly stumble over new exciting results. In our case, this was only possible due to the specific advantages of the CUT method, which allowed us to turn off genuine three-body interactions and to unambiguously discriminate the bound state from continuum states. The CUT method is extremely powerful and allows one to find such smoking gun features due to the advantages mentioned above. We believe that the method can be useful for many other scientists researching strongly correlated systems, as this opens new avenues for exploring materials via multi-particles bound states. One fascinating goal can be to identify three-particle or higher number bound states in other physical systems held together by genuine three-particle interactions.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Physics

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the physical sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Higher-order interaction networks 2024

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Physics-Informed Machine Learning

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in