Cones, sticks and croissants: Early cephalopod evolution

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Most people know cephalopods such as squid, octopus and cuttlefish from various books, documentaries, movies, aquaria, snorkelling or perhaps even as food. They are particularly famous for their cognitive abilities compared to other invertebrates – recently, a cephalopod passed the so-called Stanford marshmallow experiment, an intelligence test originally designed for children. Almost equally famous are the fossils of cephalopods, where ammonites and belemnites represent probably some of the most iconic fossils of all time: everybody who went fossil collecting a few times has probably seen at least couple of them. It might thus be surprising that the earliest fossil cephalopods are still poorly understood – and despite the great amount of available material, research on them has been somewhat neglected. In our new study published in BMC Biology, we aim to change that a bit by providing a fresh perspective on the early evolution of cephalopods using quantitative methods. Hopefully this will inspire more research in the future!

Maybe the neglectance of research on early cephalopods was caused by the fossils looking relatively boring on first glance, especially when compared to the sometimes astonishingly beautiful ammonites. Rousseau H. Flower, one of the most prolific researchers on early cephalopods in the past century who single-handedly named more than 400 species, once wrote about endocerids (a group with very long slender straight shells) that “a collection of them seems about as fascinating as a collection of telegraph poles”. As with many things, the true beauty lies hidden beneath the surface. Cutting and polishing fossils of early cephalopods reveals an astonishing diversity of forms in their internal shell structures that essentially served as a buoyancy device. This is also what makes them so fascinating to me personally, because they show so many different morphologies that have no modern analogues.

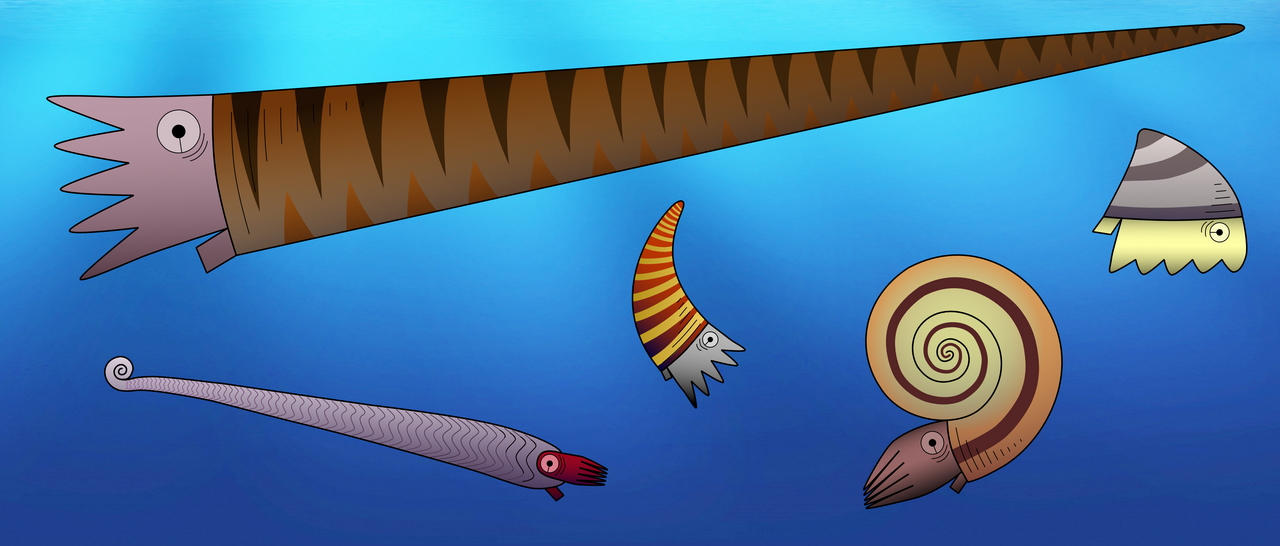

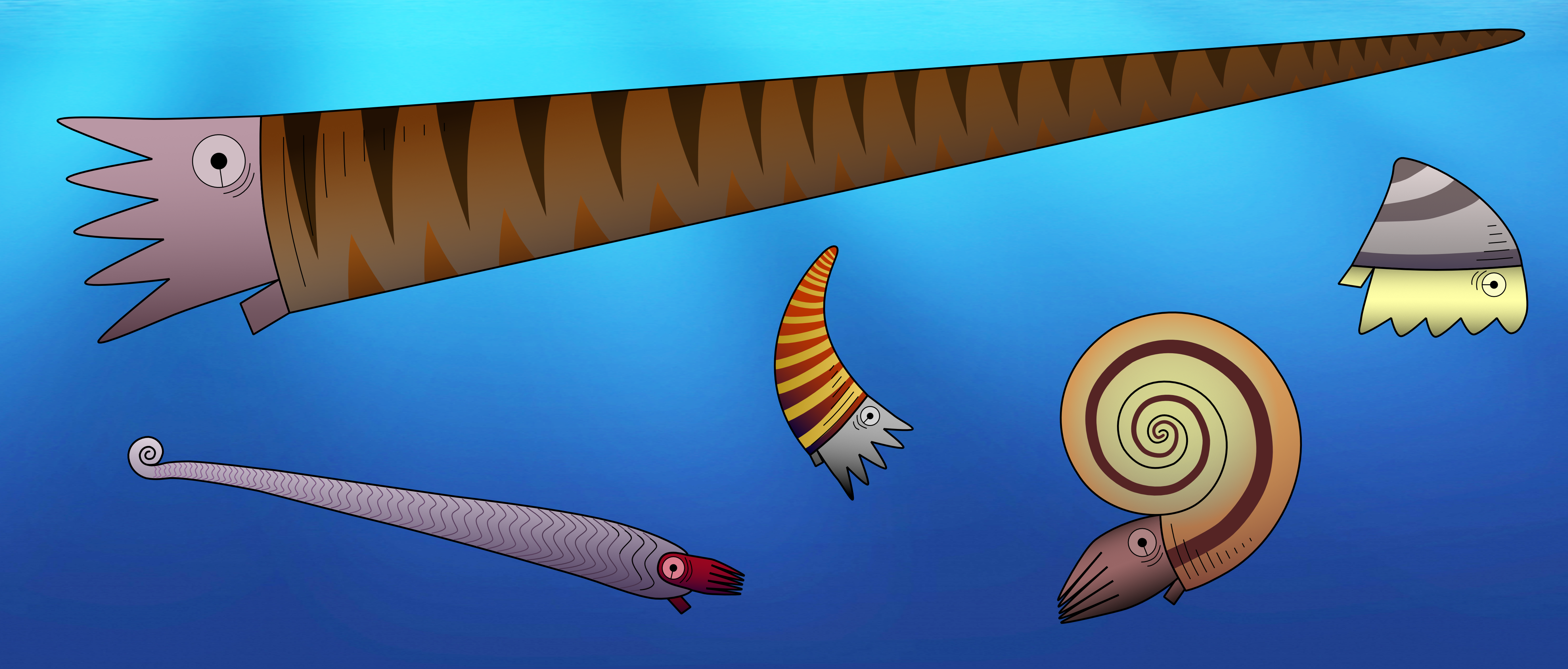

One important feature to distinguish between different fossil species of externally shelled cephalopods is the siphuncle. This is a tube that runs through their chambered shell and pumps out water to replace it with gas, essentially allowing the animal to become a little submarine, as seen in the only living cephalopod with an external shell, Nautilus. In Nautilus, the siphuncle has a relatively simple shape, as it basically consists of a thin straight tube. However, early cephalopods exhibit a great variety of siphuncle shapes, from thin to very broad and everything between siphuncles with very strongly expanded segments to concave segments and with various strange calcified structures that grew inside the siphuncle or even within the chambers (endosiphuncular and cameral deposits). Add to this the variety in external shell shape that basically ranges from long sticks to cones, croissants, drops, spirals and some others, and you get a large spectrum of different combinations of morphological structures (Fig. 1). And of course, these morphological characteristics had a very direct impact on the lives of these animals, as they directly controlled their swimming capabilities, e.g., the efficiency of buoyancy adjustments, manoeuvrability, swimming speed, etc. This means that there were probably a lot of different lifestyles and ecological roles among early cephalopods. It is hard to imagine how they might have looked like, but some of them may seem really strange to us (Fig. 2).

The big question is here: how did these diverse forms evolve and how are all these groups related to each other? In the past, there have been multiple attempts to solve this, and different evolutionary scenarios have been proposed. The problem was that different researchers focussed on only few, but different characters to reconstruct their evolutionary trees and thus reached different, often contradicting results. In our study, we took a different approach by collecting a large amount of morphological data and analysing them quantitatively with state-of-the-art methods, i.e., Bayesian inference and the so-called Fossilized Birth-Death model. According to our results, early cephalopods diverged quite early into three major groups (Fig. 3): The Orthoceratoidea (mostly slender straight shells with calcified deposits within their chambers and siphuncles), the Multiceratoidea (very disparate shell shapes and thus hard to define, but generally ventrally enlarged muscle attachments and empty siphuncles) and the Endoceratoidea (sometimes very large straight to slightly curved shells, with characteristic conical deposits called endocones within their siphuncles).

In our paper, we go into detail about each of these groups and the methods. Here, I want to focus a bit more on the real heart of the paper: the morphological character matrix. Building a character matrix from the ground up was a challenging and long process that I started in 2017. Very roughly, my approach was as follows:

- Intensive literature research, reading through countless papers, some of them in Russian or Chinese (luckily, modern translation tools are available and work relatively well for this purpose).

- Defining characters and character states.

- Looking at specimens in Museum collections and the published literature to score characters and measure proportions.

- Realising that I need additional characters or change existing characters to capture some of the variation, thus revisiting all the previously scored species.

- Repeat 3. and 4. many (!) times.

- Check all species again, asking co-authors for their opinions, repeat 3. and 4. again where necessary, final revisions of characters.

As you can imagine, this was a very long process, but also very instructive at the same time and I was repeatedly perplexed by the strangeness of some of these extinct animals. During this entire process, I stumbled upon multiple cases where definitions of characters were problematic (perhaps no wonder, as they were not defined with phylogenetic analysis in mind) or where different names were applied for the same thing. Our paper is thus accompanied by an extensive supplementary material, which discusses every single character in detail and will hopefully prove helpful in future research.

I was lucky to be supported by an awesome, international team of co-authors (Fig. 4) from seven countries (Switzerland, Finland, Germany, United Kingdom, Czech Republic, Argentina and China), which helped a lot in above step 6, but also whenever I had questions or in preparation or revision of the manuscript, so a huge thanks goes to Björn, Rachel, Andy, Dave, Martina, Marcela, Xiang and Christian!

Interested in the full article? Be sure to check it out here:

Early cephalopod evolution clarified through Bayesian phylogenetic inference

Follow the Topic

-

BMC Biology

This is an open access journal publishing outstanding research in all areas of biology, with a publication policy that combines selection for broad interest and importance with a commitment to serving authors well.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Organoids: advancements in normal development and disease modeling, and Regenerative Medicine

BMC Biology is calling for submissions to our Collection on Organoids: advancements in normal development and disease modeling, and Regenerative Medicine. This Collection seeks to bring together cutting-edge research on the use of organoids as models of normal organ development and human disease, as well as transplantable material for tissue regeneration and as a platform for drug screening.

Studies can be based on organoids derived from either induced pluripotent stem cells or tissue-derived cells (embryonic or adult stem cells or progenitor or differentiated cells from healthy or diseased tissues, such as tumors).

We welcome submissions focusing on studies investigating the mechanisms of self-organization and cellular differentiation within organoids, and how these processes recapitulate human tissue architecture and pathology. We are especially interested in studies addressing the issues of improving tissue patterning, specialization, and function, and avoiding tumorigenicity after transplantation of organoids. We will also consider studies that demonstrate the application of organoids in personalized medicine, such as drug screening, toxicity testing, and the identification of novel therapeutic targets.

We are interested in studies focusing on the refinement of methods to enhance the fidelity and functional maturity of organoids, especially those integrating organoid models with cutting-edge technologies such as advanced imaging, single-cell and spatial omics, microfluidic chip systems and bioprinting.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3: Good Health and Well-Being.

All manuscripts submitted to this journal, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 15, 2026

Environmental microbiology

BMC Biology is calling for submissions to our Collection on Environmental microbiology. Environmental microbiology is a rapidly evolving field that investigates the interactions between microorganisms and their surrounding environments, including plants, soil, water, and air. This area of research encompasses a diverse range of organisms, from bacteria and protists to extremophiles, and seeks to understand their roles in various ecological processes. By examining microbial communities and their functions, researchers can gain insights into plant-microbe interactions, biogeochemical cycles, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem dynamics. Furthermore, the study of the microbiome in different habitats is crucial for understanding biodiversity, ecosystem resilience, and the potential applications of microbes in environmental remediation. Advancements in molecular biology and bioinformatics have significantly enhanced our understanding of microbial ecology and the intricate relationships that underpin environmental systems. Understanding these interactions is essential for addressing pressing global issues such as climate change, pollution, and ecosystem degradation to develop sustainable strategies for environmental conservation and restoration.

Potential topics include but are not limited to:

Plant-associated microbes in sustainable agriculture

Microbiomes and symbioses in aquatic ecosystems

Microbial contributions to biogeochemical cycles

Community structure and dynamics in soil, water, air, and extreme environments

Extremophiles and their ecological significance

Pathogen Ecology

Host-Microbe Environmental Interactions

Effects of climate change and environmental stressors on microbial communities

Methodological Advances in environmental microbiology

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 6: Clean water and Sanitation, SDG 13: Climate Action, SDG 14: Life Below Water, and SDG 15: Life on Land.

All manuscripts submitted to this journal, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 25, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in