Controllable branching of robust response patterns in nonlinear mechanical resonators

Published in Physics

A harmonic oscillator is probably one of the most important physical concepts since the perfectly parabolic potential is a good approximation at most local potential minimum. In this ‘behind the paper’, we explore the fascinating dynamics generated by one linear oscillator coupled to one harmonically driven weakly nonlinear mode.

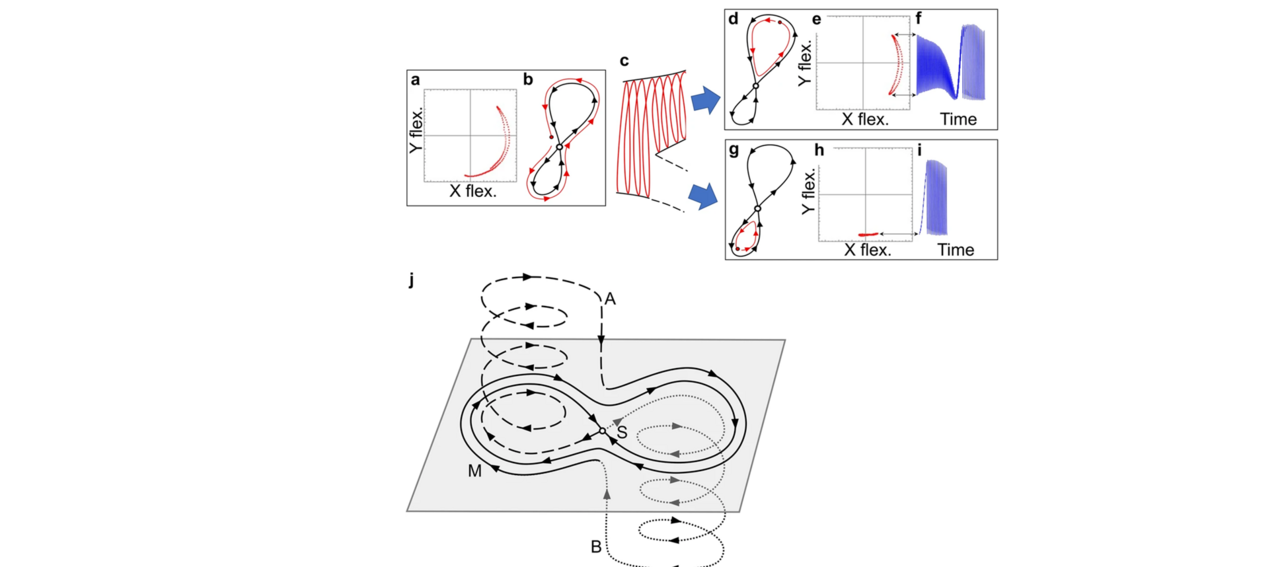

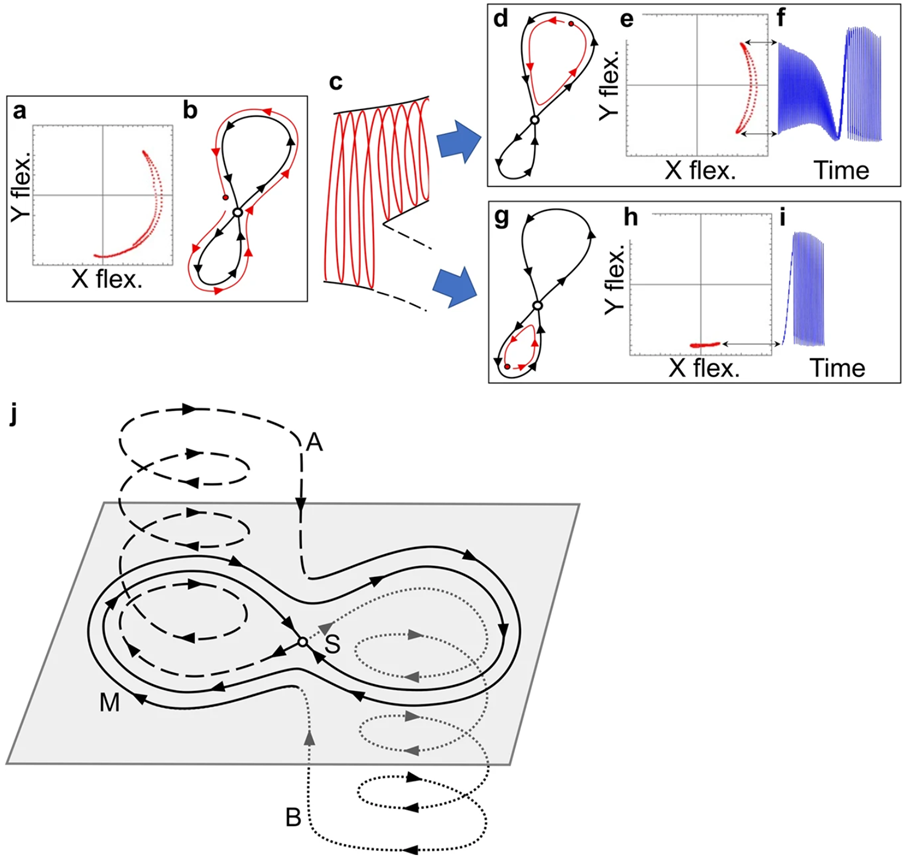

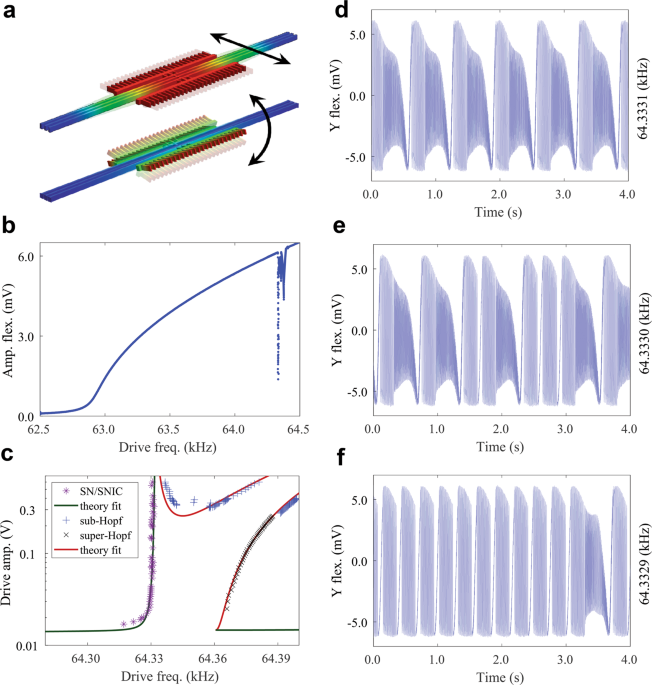

We studied a mechanical resonator where two vibrational modes were interacting in a 3:1 internal resonance (IR). When approaching the IR, the system underwent a saddle-node on invariant circle (SNIC) bifurcation (Fig1e), generating long-term repetitive trajectories in phase space. Interestingly, the trajectories were alternating between heavily oscillating structures and periods of calmer dynamics, very similar to ‘bursting’ – a nonlinear phenomenon observed in, e.g., neural dynamics, and the mechanical resonator was even proposed to be a test bench for neural dynamics.

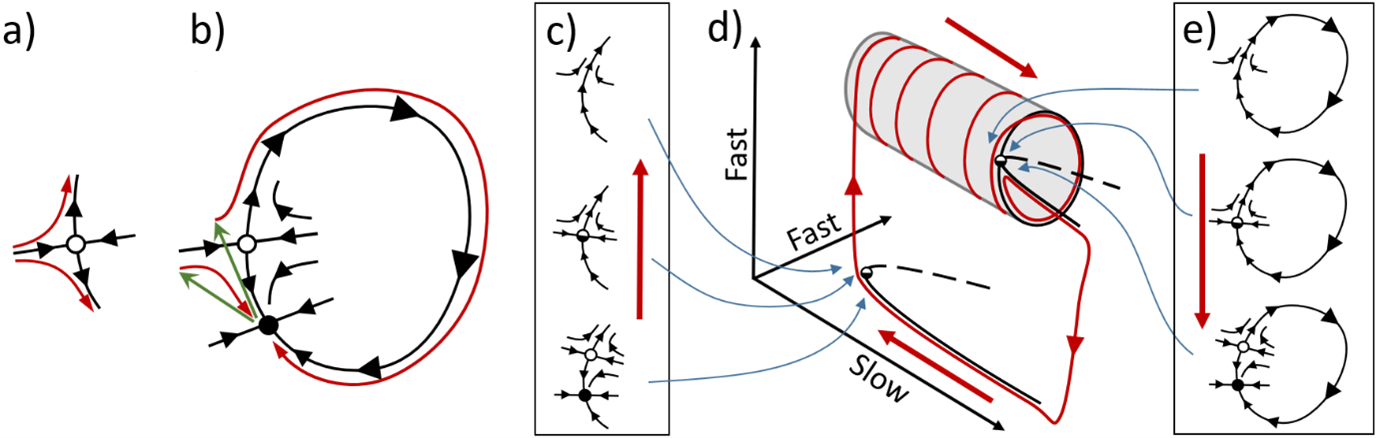

One amazing thing about nonlinear dynamics is that the very same concepts from the nonlinear toolbox can be applied at vastly different scales and scientific fields. Bifurcations are a class of features in our toolbox that describe transitions between qualitatively different responses in nonlinear dynamic systems. In bursting, there is a separation of timescales between a set of fast variables and at least one slow variable. In bursting, the fast variables oscillate heavily until the slow variables generate a bifurcation, which annihilates the oscillating structure, leading to a calmer or even stead state. As the slow variables continue to slowly drift, the calm state is eventually annihilated, causing the fast dynamics to oscillate again. Furthermore, there is a plethora of different bursters, which are classified and thus named by the bifurcations responsible for the transitions.

The long trajectories generated by our mechanical resonator showed all the characteristics one would expect of a burster. Hence, by setting up a nonlinear dynamical model, we started to hunt for the bifurcations in order to classify the burster. We found saddle-node bifurcations, which could be responsible for the transition from the calm to the oscillatory dynamics. However, we couldn’t find any bifurcation which annihilated the oscillatory structure. In fact, in the fast variable subsystem, we couldn’t find any stable (nor unstable) ‘limit cycle’ whatsoever. Puzzled by this absence, after several months of work, we went beyond the standard analysis for slow/fast dynamical systems and found that not even the saddle-node bifurcations were involved in the transitions.

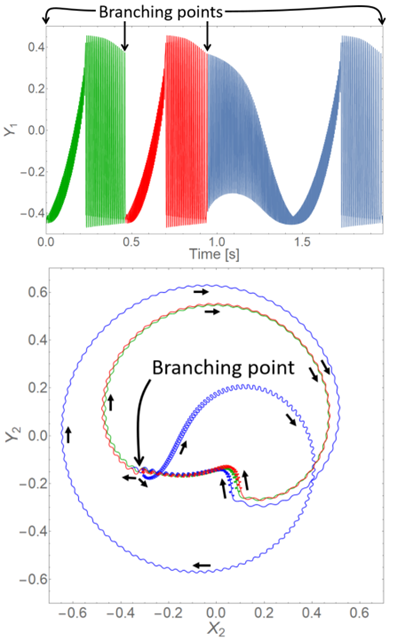

Instead, the observed phenomenon occurs due to a branching mechanism which enables switching between the robust oscillatory trajectories (Fig2). Furthermore, due to the structure of the branching mechanism (Fig3), it is not only able to switch the dynamics between large amplitude oscillations and calmer small amplitude oscillations, it can also branch the dynamics into distinct robust responses - a feature which would not be generated in a ‘bifurcation-driven’ burster.

The dynamics can be thought of as a ski-slope system, where each slope represents a robust trajectory (green+red and blue) in which a skier (the state of the system) can oscillate on its way down. A slope can branch into two slopes when the skier hits a saddle structure, and the branches can then branch again or recombine into a common robust structure (see movie).

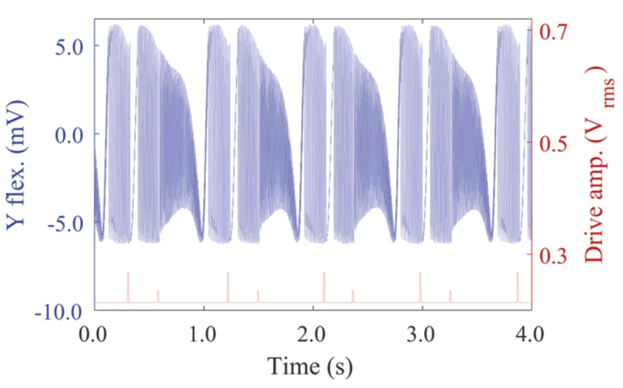

In the ‘uncontrolled’ system, where the dynamics is only driven by the single-frequency drive, the dynamics at the branching point is dominated by noise, leading to stochastic switching between trajectories. Hence, by sending in a small control pulse each time the system approaches the branching points (Fig4), we can control which of the two trajectories to is executed. Importantly, if the same pulses are applied when the system is not close to the branching point, the pulses have no appreciable effect, i.e., the trajectories themselves are robust to perturbations away from the branching points.

We experimentally found that several branching mechanisms can be active at the same time, creating a network of robust links. Using the small control pulses, one can navigate in the network. Furthermore, by adjusting parameters, we can bias the mechanism to always fall into the same loop and execute the same trajectory.

Coupled oscillators, as the ones considered here, are present in a wide range of systems spanning physical, chemical, and biological systems. As demonstrated here, this branching mechanism is present in these systems, but the generality of the mechanism goes beyond coupled oscillators since only the general structure in Fig.3(j) is required. Hence, we believe that this branching mechanism can be a useful item in the toolbox of nonlinear dynamics among bifurcations and other concepts. It could potentially be useful to explain repetitive execution or transitions in the execution of system behavior. However, in comparison to more complex systems, such as fixed action patterns in animals, the multifaceted response of the mechanical resonator offers a much cleaner and more well-defined repertoire of robust behaviors. There is, therefore, potential in using these mechanical oscillators as testbeds to develop other springboard concepts for the understanding and control of more sophisticated systems spanning many diverse domains.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in