COP30? It’s time to talk about soy on Indigenous lands

Published in Social Sciences, Ecology & Evolution, and Arts & Humanities

We—mostly urban dwellers—often hold a romanticised image of Indigenous communities: living simply, stewarding pristine landscapes, and drawing subsistence from nature. COP30 reinforces this image, referring to Indigenous peoples as “Guardians of Biodiversity”1

In many places, especially in northern Brazil and other regions around the world, this holds true. Indigenous territories overlap with ~85% of Earth’s protected areas, safeguarding some of the planet’s last intact ecosystems2. Their knowledge is fundamental for biodiversity conservation and sustainable futures3. Recognising and protecting Indigenous rights is essential.

But not all Indigenous realities look like the COP narrative. In southern Brazil, Indigenous communities have faced decades of land conflict, displacement, and forced integration into urban areas. Violent disputes over land recognition continue today4. In some regions, Indigenous groups are now embedded within cities, profoundly altering their relationship with the land5,6.

Agribusiness — the engine of Brazil’s economy — is a major driver of these conflicts. Over 20% of Brazil’s GDP depends on soy, grains, and meat production7. The southern states of Paraná (PR), Santa Catarina (SC), and Rio Grande do Sul (RS) are among the country’s top agricultural producers8. Expanding production requires land—and land pressure fuels illegal encroachment into Indigenous territories.

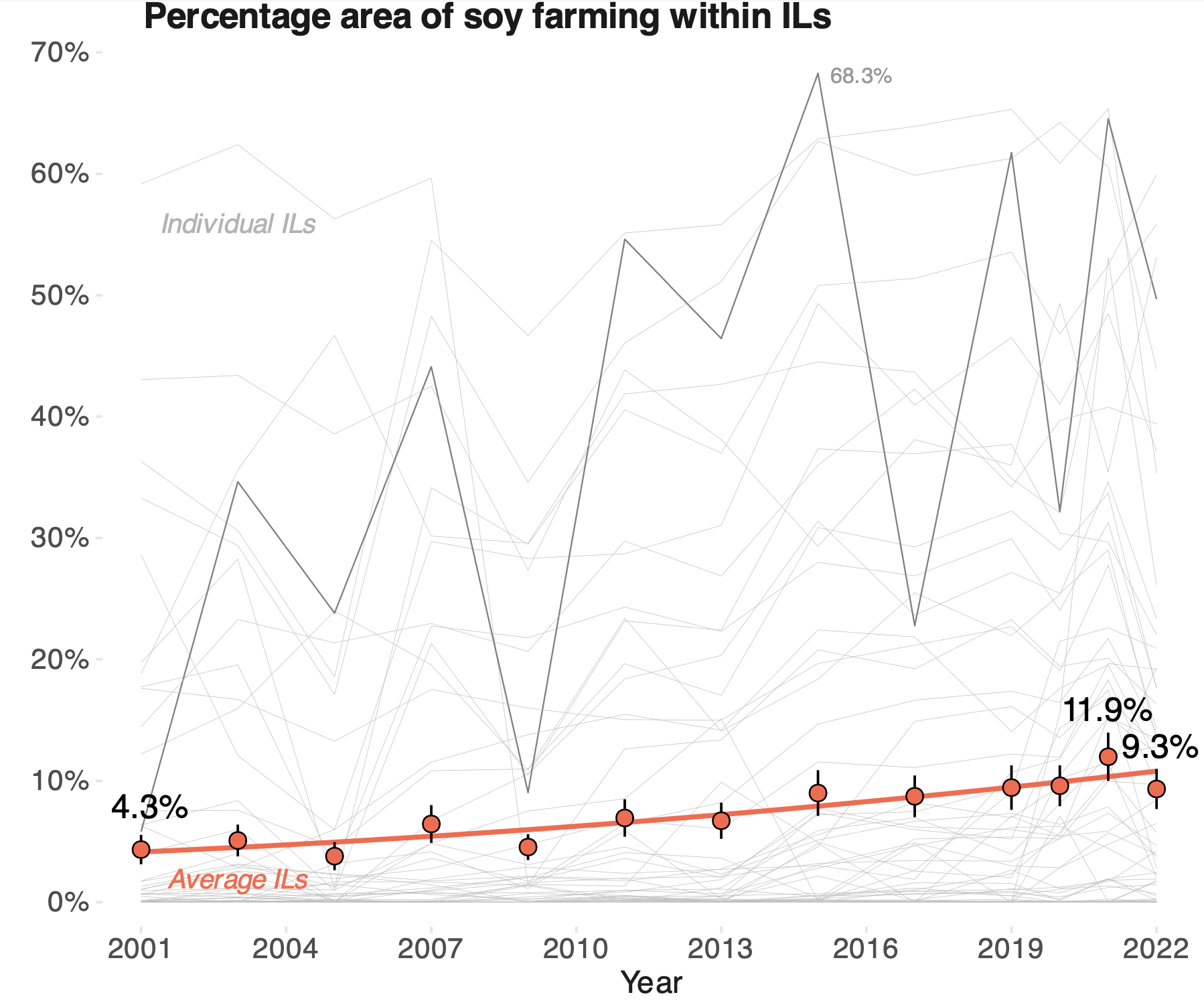

Using public data, we found that illegal soy farming inside Indigenous lands in southern Brazil increased by an average of 116% between 2001 and 20229. In particular, Paraná (PR) experience ~127% increase, followed by Santa Catarina (SC) with ~121% and Rio Grande do Sul (RS) with ~106% (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Average increase in soy planted area within Indigenous land in Brazil’s southernmost states.

Some Indigenous lands have been more than 60% covered by soy. In several places, large modern harvesters operate inside Indigenous territories—landscapes indistinguishable from commercial farms (Fig 2). This disrupts not only ecosystems but also our assumptions about what Indigenous lands look like. These communities are facing a unique form of pressure: not

to protect the forest, but to farm it.

Figure 2. Inside of an Indigenous land suffering with encroachment in Paraná showing expensive harvesting machinery operating freely.

Why expelling illegal actors won’t work. A simplistic solution would be to remove illegal farmers. But encroachment persists because of deeper systemic failures. When the State does not deliver basic services—healthcare, transport, social assistance—the agribusiness steps in. In exchange for minimal support, they gain access to Indigenous land and labour. The soy produced enters a “parallel market,” sold below official prices, benefiting agribusiness more than Indigenous communities. This dynamic fuels internal inequality. We observed families within the same community who are excluded from these deals and the financial benefits they generate. As a result, illegal land leasing can lead to social disintegration where internal conflicts are exacerbated, undermining group cohesion. This is an ideal scenario for non-Indigenous soybean producers to exploit and manipulate such disputes to advance their economic interests.

A different approach: legalise and regulate soy on Indigenous lands. Instead of fighting a battle already lost on the ground, we propose:

- Legal, monitored soy production within Indigenous lands, structured similar to fair trade.

- Full price sales—no more parallel market exploitation.

- Revenue controlled by Indigenous communities.

Legalisation—combined with strict monitoring—could ensure that land use decisions remain in Indigenous hands and that profits drive community development rather than external exploitation.

We are not arguing that soy farming is risk-free. Stratification and internal power dynamics may persist. But, unlike the current situation, Indigenous communities would have:

- control over their land,

- ownership of the production process,

- financial returns enabling social and economic development.

Will this harm biodiversity? Not necessarily. Maintaining the status quo almost guarantees ongoing unregulated destruction. A monitored system—designed around biodiversity goals—offers a chance to:

- reduce clandestine deforestation,

- improve land-use planning, and

- integrate Indigenous communities into Brazil’s economic prosperity.

Agribusiness is critical to Brazil’s economy—local, regional, and national. But prosperity does not need to come at the expense of Indigenous peoples or biodiversity. Integrating Indigenous communities into value chains, rather than marginalising them, creates long-term incentives for conservation. We hope COP30 will recognise these complex realities and move beyond romantic narratives. Indigenous communities must be participants in development, not symbols of it.

Paper

Kamaroski, F., & Morimoto, J. (2025). Indigenous Lands Turned into Soy Farms Pose Threats to Sustainability in Brazil. Sustainability, 17(21), 9918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219918

References cited

- https://cop30.br/en/news-about-cop30/guardians-of-biodiversity-brasil-coordinates-largest-indigenous-participation-in-cop-history.

- Schmidt, Paige M., and Markus J. Peterson. "Biodiversity conservation and indigenous land management in the era of self‐determination." Conservation Biology23, no. 6 (2009): 1458-1466.

- Brandão, Diego Oliveira, Julia Arieira, and Carlos Afonso Nobre. "Pathways from Deforestation to Restoration: The science is clear: rehabilitating the Amazon rainforest is essential to mitigating climate change and reversing biodiversity loss. Indigenous knowledge must play a central role." NACLA Report on the Americas55, no. 2 (2023): 124-131.

- https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2025/07/14/jovem-guarani-e-decapitado-ao-lado-de-carta-com-ameaca-as-comunidades-indigenas-do-pr/

- (https://www.curitiba.pr.gov.br/noticias/adaptados-a-vida-urbana-moradores-de-aldeia-no-campo-de-santana-ainda-preservam-sua-cultura/39476;

- Faustino, R. C., Novak, M. S. J., & Mota, L. T. (2024). Kaingang Children Urban Spaces: Cultural Learning and Indigenous Sustainability in Paraná. Educar em Revista, 40, e88551

- da Silva Medina, G., & Pokorny, B. (2022). Agro-industrial development: Lessons from Brazil. Land use policy, 120, 106266.

- https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-sala-de-imprensa/2013-agencia-de-noticias/releases/26537-ibge-preve-safra-recorde-de-graos-em-2020

- Kamaroski, F., & Morimoto, J. (2025). Indigenous Lands Turned into Soy Farms Pose Threats to Sustainability in Brazil. Sustainability, 17(21), 9918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219918

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in