Cytoskeletal stiffening in synthetic hydrogels

Published in Chemistry

Hydrogels are increasingly used for 3D cell culture applications. In these cultures, we find that the cells can be very responsive to the mechanical properties of the hydrogel. Their behaviour in soft gels may change a lot to that in stiffer gels.

After the cell culture starts, however, the gel properties are difficult to manipulate. This is awkward, since in their natural habitat, i.e. the body, the (mechanical) environment of the cell is never constant. So far, the main method to stiffen a gel in-situ is to simply generate more crosslinks; in fact, many more crosslinks to achieve an appreciable step in stiffness. This change in architecture simultaneously induces strong changes in all other gel properties including its pore size. Moreover, crosslinking methods (or light-driven removal of crosslinks) tend to be fully irreversible, allowing only a single change in mechanics during a 3D cell culture experiment.

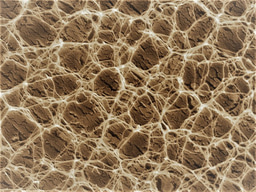

Figure 1 | Hydrogel composite made of the semi-flexible and strain-stiffening PIC (red) and the thermosensitive PNIPAM (red) giving stiffening interpenetrating hybrid gels. As the temperature reaches 33 °C, the PNIPAM collapses and strains the PIC gel that becomes much stiffer. The response is fast and reversible.

In our work, we present a completely different approach to stiffening (Figure 1). Here, we use the strain-stiffening properties associated with semi-flexible networks; networks that are often found in biology, but not in synthetic materials. Examples include our bodies’ most prevalent proteins: fibrin, collagen, actin and intermediate filaments. Semi-flexible networks become many times stiffer under deformation. We present composites based on a synthetic strain-stiffening material polyisocyanide (PIC) with the thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM). As the PNIPAM contracts at the thermal transition, it internally strains the mechanically sensitive PIC gel, which stiffens enormously.

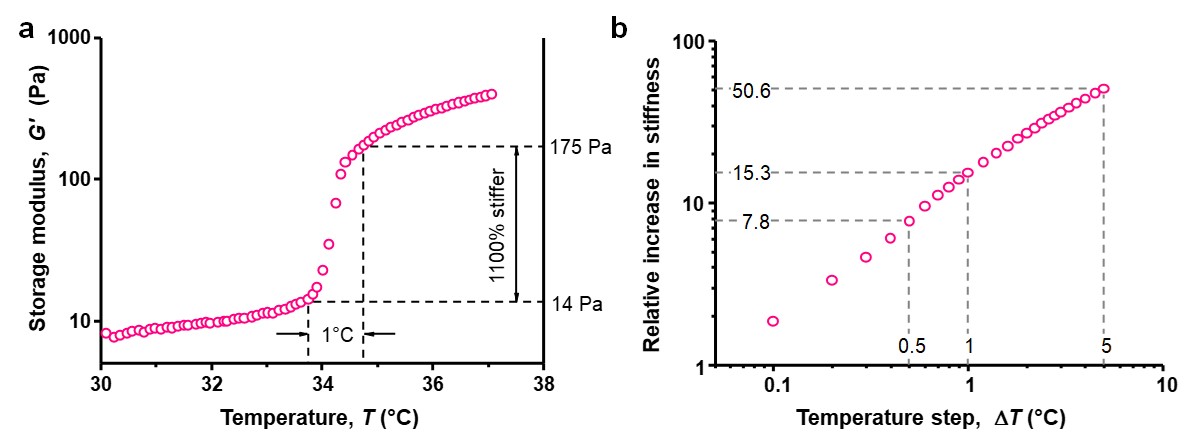

This mechanism has great advantages: The stimulus for a large change is very small. A gel can become more than 10 times stiffer in only 1 °C or an amazing 50 times in just 5 °C (see Figure 2). In addition, the response is instantaneous and completely reversible; cooling returns the soft gel. In the manuscript, we detail how the stiffening transition is tunable, both in temperature and in extent.

Figure 2 | Thermal stiffening of gel composites. a, PIC/PNIPAM gel (1/17 mg mL–1) stiffen more than 10 times in less than 1 °C. b, Maximum available stiffness jump, defined as G′T+ΔT/G′T for a temperature window ΔT, for the hydrogel PIC/PNIPAM 1/17 at a heating rate of 0.1 °C min–1. The hybrid IPN stiffens about 8 fold in 0.5 °C, 15 fold in 1 °C and 51 fold in 5 °C.

When looking back at biology, we find that our stiffening mechanism is truly analogous to stiffening in the actomyosin cytoskeleton. Here force generation is completely different, since myosin motors provide the required force through chemical actuation, but the network response of the actin is completely the same. In fact, our measurements shows that forces in our material correspond quantitatively to those in actomyosin.

What should we do with these unique adaptive materials? Of course, they may be applied as dynamically switchable cytoskeletal components in synthetic cell-like systems triggered by a small thermal (or other) cue. More interestingly, the small temperature step and reversible mechanism allows one to control the mechanical properties in a cell growth studies where now, we are able to precisely and dynamically control the cellular mechanical environment at any time.

Read more details in the open access manuscript. Reference: Paula de Almeida et al. Cytoskeletal stiffening in synthetic hydrogels. Nat. Commun. 10, 609 (2019).

More information on:

- biomimetic PIC hydrogels: Nature 2013, Nat. Commun. 2014, Nat. Commun. 2017, Nat. Commun. 2018.

- biological applications of PIC hydrogels: Nat. Mater. 2016, Biomaterials 2018, Biomacromolecules 2019.

Contact:

E: p.kouwer@science.ru.nl

W: www.ru.nl/molecularmaterials

T: @KouwerLab

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in