De-paving paradise, one parking space at a time

Published in Sustainability

This paper arose from an awareness that I suspect haunts a lot of sustainability researchers: we are not doing enough.

In this case, the 'not doing' is in cities, where we are very good at talking about the merits of urban greening, and much less good at delivering it. This reality crashed home for me a few years ago, when I looked up a couple of key strategic documents for Melbourne, where I live and work, and quantified the amount of land use change we actually need to deliver if we want to avoid significant climate impacts. It is, in short, radical.

Our central city's watershed is over 80% asphalt and concrete, and rated 'extreme' for flood risk. We have a strategy to reduce this risk by 2030; it needs us to de-pave 65 hectares of dense urban land. For perspective, the biggest park in this catchment is just 24ha, and that was established over a century ago. Clawing back dozens of hectares of space in our city's heavily contested streetscapes would be an incredible feat - and, while on paper we have just eight years to hit that target, the huge flooding we've seen in a number of cities on the Australian east coast makes it feel like we might need to move even faster.

Our city is also subject to intense heatwaves (with multiple days above 40c/104f), and the strategy to handle that is perhaps even more ambitious; we need 40% tree canopy, by 2040. Right now we’re at 23%, with a lot of canopy in parks instead of streets. Getting to 40% means finding over 180ha of new tree canopy, a truly massive area in a small inner-city local government where it’s a fight to just protect the trees that we already have.

The sheer demand for space that I saw in those documents left me slightly obsessed with the question of how we can find space for nature in cities. Without a lot of land, all our talk of urban greening remains just talk. How can we carve out that much land in cities where it’s often scarce, expensive, and already used for other things?

We think the answer looks a little like this:

Figure 1: Visualisation of a real opportunity we identified on Faraday Street, Melbourne.

Once you're interested in how we allocate space in cities, you quickly get interested in car parking. Cities tend to dedicate vast areas to parking, and a lot of it is in buildings. This is because planning rules in many cities have historically mandated that as new buildings are built, they integrate generous car parking garages, designed to cater to theoretical peak demands. This requirement is starting to be rolled back now, but it’s left its mark; central Melbourne has 460 hectares of parking, with much of it in buildings (~50ha on street, the rest in garages).

The point that really convinced me to write this paper was a statistic about the vacancy of these garages. A 2018 study found that 26-40% of apartment car parking spaces in the inner city are simply empty. This highlighted a huge rate of redundancy in urban land use: we are storing cars on streets, when there is space in buildings. This is wasteful use of a scarce resource. What would happen if we parked more cars in garages to free up precious space in our hot, flood-prone city streets?

The answer was quite unexpectedly substantial. I ran a series of GIS scenarios looking for redundant parking, which I defined as street parking within a two minute walk of a large garage with vacant spaces. Even with conservative assumptions, I found thousands and thousands of street spaces, often right next to large garages. With these mapped out, I began to assemble a team to really understand what this could mean for our city.

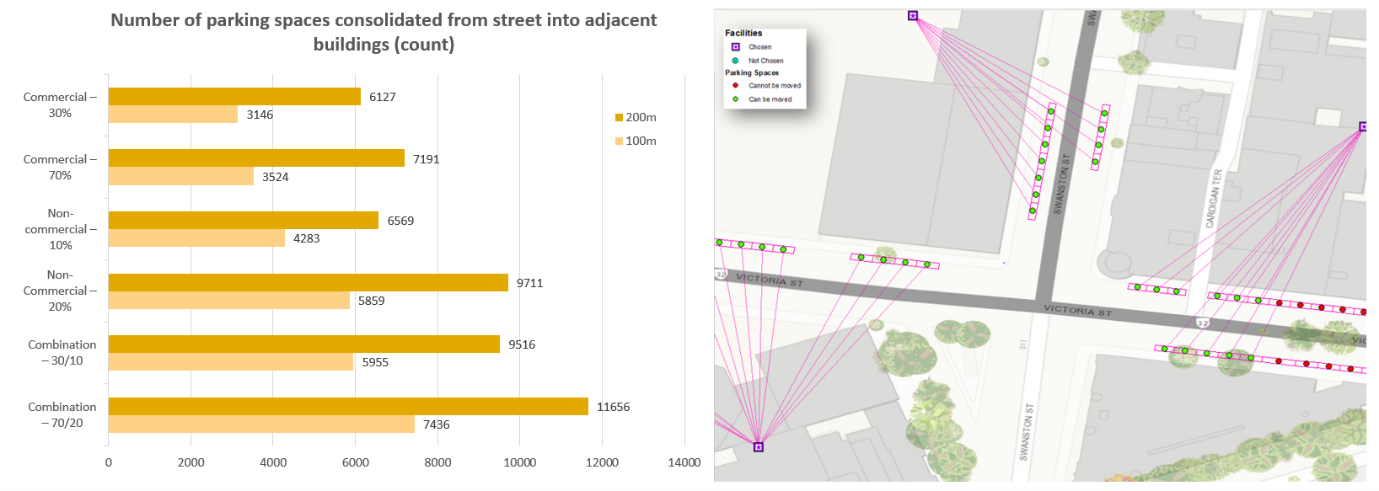

Figure 2 - We ran 12 scenarios, testing different utilisation rates of different kinds of parking, at a walking distance of 100m and 200m. The map on the right shows an output of the initial analysis, with redundant parking spaces (green) consolidated into nearby garages.

Quickly I had an interdisciplinary group that was so diverse that it might have been the setup to a very obscure dad joke:

“Three ecologists, an architect, an urban forester, a water engineer, two geographers and a planner walk into a bar…”

Despite this unusual mix, the team operated quite seamlessly. We mapped out where parking could be replaced, then developed a design to show what might replace a parking space: a modular green space, designed to be simple and replicable, but with enough of the details thought out that it’d work in real settings. This was the basic design that we modelled:

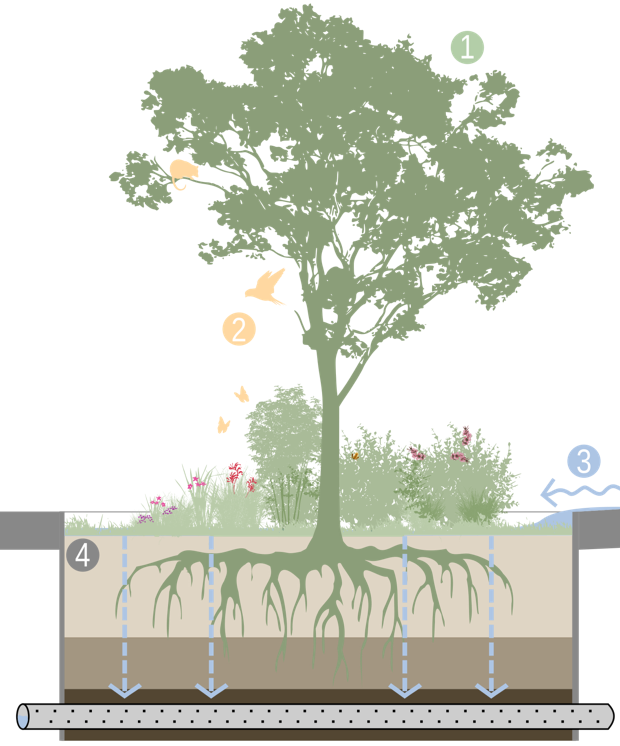

Figure 3: Key elements of the design that replaces a parking space include (1) A canopy tree, (2) inclusion of habitat features such as understorey planting and flowering trees (3) a sunken 'raingarden' design that intercepts stormwater and (4) de-paving of the entire parking area.

Figure 3: Key elements of the design that replaces a parking space include (1) A canopy tree, (2) inclusion of habitat features such as understorey planting and flowering trees (3) a sunken 'raingarden' design that intercepts stormwater and (4) de-paving of the entire parking area.

The next step was to model the total benefits of these spaces, if we replaced the thousands of redundant parking spaces our mapping identified. Our team modelled tree canopy growth, ecological connectivity and stormwater treatment and interception. We found some really substantial results: up to sixty hectares of new tree canopy, thousands of tonnes of stormwater pollutants intercepted, and a lot of fragmented habitat re-connected.

Figure 4: Canopy creation under one of our modelled scenarios.

Figure 4: Canopy creation under one of our modelled scenarios.

One of the real pleasures of the design and modelling process was working between professions. Our canopy modelling specialist approached our ecologists to advise on a set of tree species that would provide suitable habitat for native birds and insects. Our architect got to know our water engineer because they needed to get the drainage details right for our designs, which incorporate ‘raingarden’ features. We all learned a bit about how tree planting can work around typical barriers in streetscapes, like underground cables and high-speed traffic. Our new friends in geography and urban planning helped us understand how this remarkable redundancy actually eventuated, and why it’s so common in cities around the world.

With the study accepted, we began to think about how this might best appeal to Melbourne residents. We contracted a landscape architecture firm to visualise the impact of the changes on a local street, with a strict brief to keep it realistic. The result (which you saw at the top of this article) is still rather unreal to me, but I struggle to fault it: we’ve thought it all out, and it really is possible.

You can find our study here. Here’s hoping these findings spark some change in the streets of our cities.

Follow the Topic

-

npj Urban Sustainability

An open access, online-only journal for urban scientists, policy makers and practitioners interested in understanding and managing urbanization processes.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Urban Nature-Based Solutions and Water

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Sep 23, 2026

Radical Civic Practices: The Future of Urban Environmental Justice Studies in a Highly Unequal World

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 10, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in