Deciphering the links between telomere attrition and clonal hematopoiesis

Published in Cancer, Cell & Molecular Biology, and General & Internal Medicine

The problem

Billions of blood cells are produced every day in our body from a limited pool of long-lived hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Like all human cells, HSCs steadily acquire somatic DNA mutations throughout life. Whilst most of these mutations are inconsequential, some can alter HSC behavior leading in some cases to an increased ‘fitness’ of these cells, driving them to expand clonally and occupy a steadily increasing portion of the HSC pool, a phenomenon known as ‘clonal hematopoiesis’ (CH).

In the decade since it was first described, our understanding of CH has developed at an extraordinary pace. We now have a good understanding of the types of mutations driving CH, their differential impact on the rate of clonal expansion and risk of progression to blood cancers such as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the influence of the inherited genome on CH risk, and the association of CH with cardiovascular, renal and other non-hematological diseases. Despite this rapid progress, we still have limited understanding of the molecular process driving clonal expansion and how we might intervene to prevent the progression of CH to blood cancers, many of which are challenging to treat.

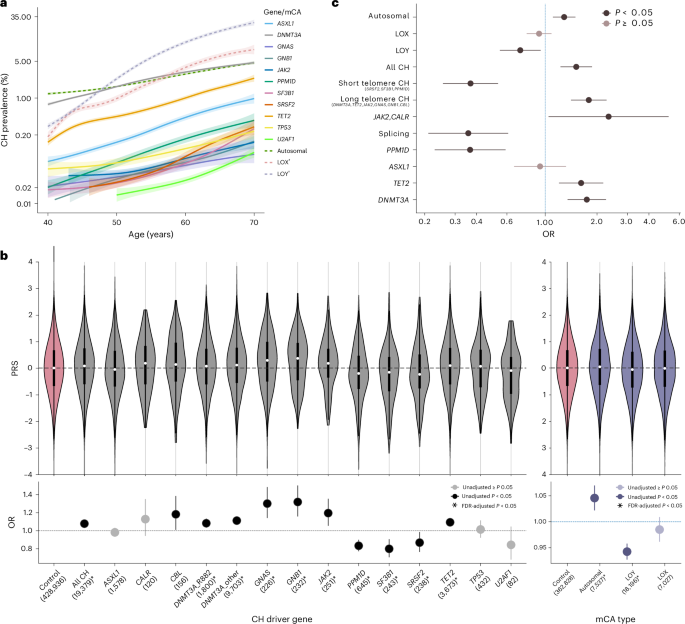

The impetus for this study arose in our past observations that CH driven by mutations in the splicing factor genes SRSF2, SF3B1 and U2AF1 displayed an unusual age-distribution: they are rarely detected before middle age but increase dramatically in prevalence beyond this. These mutations are associated with high risk of blood cancer development, yet their molecular consequences and the basis of their ability to drive HSCs to expand and engender CH remain unknown. We started the project in the hope that this unusual age-distribution may hold clues to these unknowns.

The solution

We started with a simple question: how does aging provide fertile ground for the expansion of clones with splicing factor gene mutations? To answer this, we first considered that one feature of advancing age is the shortening of HSC telomeres, and that previous studies identified links between telomere length and CH. In genome-wide association studies (GWAS), our group and others had identified germline variants in TERT, the telomerase reverse transcriptase gene, that were associated with longer telomeres and an increased risk of developing CH. This result seemed intuitive; a single HSC must divide many times to give rise to a large clone, something that would result in substantial telomere attrition. Cells with longer telomeres should therefore be able to undergo many more cell divisions, allowing them to expand to a detectable clonal size before encountering critical telomere shortening that would lead to replicative senescence.

As age-related telomere attrition could curtail HSC expansion, we speculated that it may underlie the unusual age distribution of splicing factor mutations. To test this, we turned to the UK Biobank (UKB) and investigated the association between genetically predicted telomere length and the risk of each CH subtype. This confirmed previous observations that inheritance of longer telomeres increases the risk of developing CH driven by many common driver mutations (e.g., DNMT3A, TET2, JAK2). Strikingly, we also observed that some other forms of CH were more common in individuals with shorter genetically predicted telomeres, namely those associated with mutations in splicing factor genes (SF3B1, SRSF2 and U2AF1), the PPM1D gene and loss of the Y chromosome (loss-of-Y, LOY). We posited that these mutations may rescue HSCs from the constraints imposed by shorter telomeres, offering an explanation for their association with both the inheritance of shorter telomeres and advancing age.

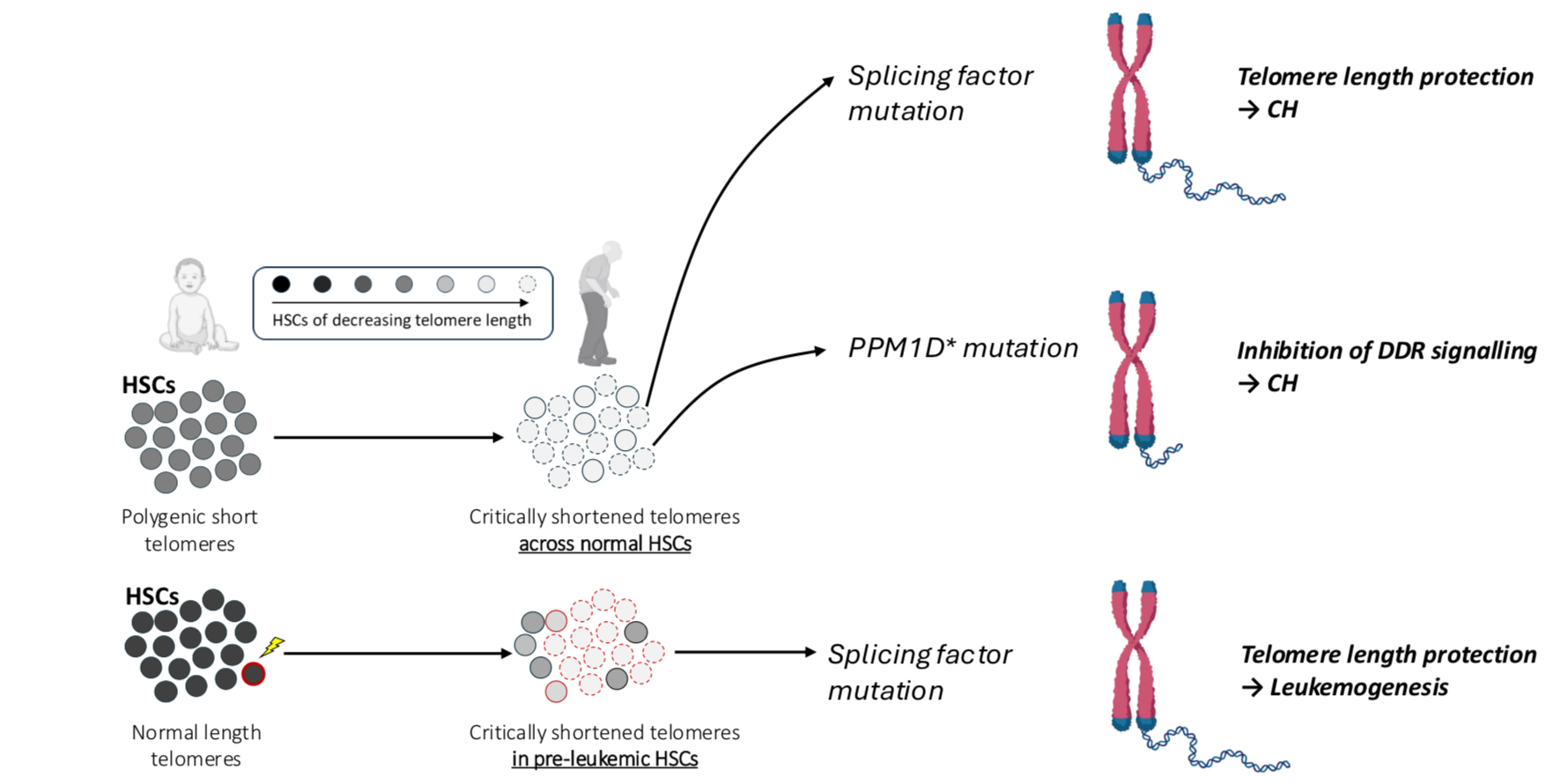

We next examined how these mutations could protect against the consequences of telomere attrition: did they i) lengthen telomeres directly, or ii) stop the DNA damage response triggered by critically short telomeres? To examine this, we compared measured telomere lengths between clones of different sizes. For PPM1D-CH, large clones exhibited substantially shorter telomeres than small clones, mirroring what we saw with CH driven by mutations in genes like DNMT3A or TET2. This suggests that PPM1D variants do not affect telomere attrition but instead protect against its consequences. As PPM1D mutations are known to attenuate the DNA damage response (DDR) associated with chemotherapy, it is plausible that a similar mechanism protects against DDR-driven senescence due to telomere attrition. Shorter telomeres in large vs small clones were also seen with LOY, but a possible mechanism here is less intuitive. Nevertheless, the Y chromosome contains very few genes, and LOY is extremely common in elderly men. It is possible that the loss of a Y-chromosome with critically shortened telomeres could attenuate senescence signaling and allow aged cells to proliferate further.

Clones with splicing factor mutations were unique amongst CH subtypes, as large clones had telomere lengths that were similar or longer than those of small clones. This suggested that these mutations were enabling cells to maintain or elongate their telomeres through successive cell divisions. Throughout the rest of the study, we provided experimental support for this hypothesis, using colony-derived whole genome sequencing and flow cytometry (telomere flow-FISH) on clinical samples. The agreement between these orthogonal approaches was essential for convincing us of the validity of our findings.

Our findings are corroborated further by a study from Gutierrez-Rodrigues et al. (Blood 2024), published during the revision stage of our paper. Here, the authors showed that similar patterns of ‘rescue’ CH occur in individuals with monogenic short telomere biology disorders (TBDs), including an increased risk of splicing factor-mutant CH, PPM1D-CH as well as CH with mutations in the promoter of TERT (TERTp-CH). We had already looked for these mutations in the UKB’s whole-exome sequencing (WES) data and did not identify any cases, but this analysis was limited by insufficient coverage in WES. However, on the suggestions of a reviewer, we then looked for these mutations in subsequently released whole-genome sequencing data and identified a substantial number of TERTp-CH cases in the UK Biobank. Notably, these showed similar age-related prevalence and genetically predicted telomere length to splicing factor-mutant CH, providing further support to our findings.

Figure 1. Telomere attrition shapes the landscape of clonal hematopoiesis (CH) and leukemogenesis with advancing age. Telomere attrition due to polygenic inheritance and/or prior clonal expansion selects for mutations in splicing factors or PPM1D, which promote CH either by protecting against telomere attrition (splicing factors) or inhibiting DDR signalling from critically short telomeres (PPM1D).

The future

Our study broadly endorses the notion that telomere maintenance is finely tuned to balance the risks of tissue aging with those of developing cancer. Deviations from the ‘average’ telomere length exist on a spectrum from mild to severe, as do the risks associated with such deviations. At the extremes are individuals with monogenic inherited variants of large effect, that either develop the clinical features of TBDs such as bone marrow failure and pulmonary fibrosis or develop cancers associated with the inheritance of ultra-long telomeres. In our study, we identify a group of individuals with less extreme variations in telomere length attributable to the interactions between polygenic variants, environmental exposures, and advancing age. Such individuals may develop some features of conditions seen in TBD, albeit with a milder presentation occurring later in life. Going forward, it will be important to consider how we might manage these individuals clinically and maintain the functioning of hematopoietic and other tissues without increasing cancer risk.

Our findings also open new avenues to target myeloid malignancies therapeutically. In particular, the observation that telomere attrition may constrain the expansion of some clones (e.g., JAK2-CH or CLL) suggests that targeting telomere maintenance could slow the proliferation of some aggressive malignancies. In the case of splicing factor-mutant CH, results from a clinical trial of the telomerase inhibitor Imetelstat revealed a significant impact on MDS with SF3B1 mutations, suggesting that targeting telomere maintenance may also be a viable option in this and other forms of splicing factor-mutant MDS.

Finally, the question of why splicing factor mutations drive CH has puzzled the field for over a decade since their discovery. Notably, each of these mutations affects splicing in different way and disrupts different mRNA transcripts, yet they are all very common drivers of MDS, a disease of aged hematopoiesis. Our study proposes a possible unifying mechanism to connect the consequences of splicing factor mutations, namely that they all interact with telomere maintenance to help overcome the attritional effects of aging on telomeres. Thus, these mutations provide a form of context-specific rescue, a mechanism also seen in some other forms of CH, such as those detected in aplastic anemia or ribosomopathies. Whilst further work is needed to identify the precise mechanisms that underly these phenomena, our work has shed light on the connection between hematopoietic aging and splicing factor-mutant CH/MDS, opening new therapeutic avenues to prevent or treat blood cancers.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Genetics

This journal publishes the very highest quality research in genetics, encompassing genetic and functional genomic studies on human and plant traits and on other model organisms.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in