Density of states prediction for materials discovery via contrastive learning from probabilistic embeddings

Published in Materials

This work is the result of an exciting collaboration between computer scientists at Cornell University and materials scientists at Caltech and LBNL. This collaboration already proved successful in predicting spectral optical absorption of complex metal oxides [3]. This time we wanted to improve further this concept and tackle the general problem of predicting spectral properties of crystalline compounds.

Spectral properties are ubiquitous in materials science. Examples are the X-ray absorption and Raman spectra, which characterize properties of crystal structure; the dielectric function which describes the interaction of material with external stimuli; and the phonon (ph) and electronic (e) densities of states (DOS) which give insight into the fundamental characteristics of the quasi-particles living in materials. Therefore, spectral properties are crucial to understanding the physical and chemical properties of materials, and they are used to drive material discovery. However, often spectral functions are usually assessed via very expensive computations, such as density functional theory (DFT) or experiments. This represents a limit in the materials discovery which largely depends on searching for materials that exhibit specific properties.

In the last decade, materials discovery has seen a large boost thanks to techniques that manage to automatize both experiments and computational workflows. These high throughput techniques have been effectively deployed in a tiered screening strategy that can effectively down select materials at the cost of reduced accuracy and/or precision.

Here is where machine learning (ML) comes into play. As demonstrated in other fields, it can provide its help in trying to predict materials properties, opening the possibility of even higher throughput primary screening due to the minuscule expense of making a prediction for a candidate material using an already-trained model. ML has already given an important contribution to materials science in predicting single value properties of crystalline materials, e.g. band gap, shear- and bulk moduli, formation energy, which are usually computed ab initio. So far, this task has been tackled successfully by using graph neural networks, which can generate a latent representation of a material from its composition and structure thanks to their enhanced representation learning capabilities.

Spectral properties are more complex objects than scalar properties. They can be seen as a probability distribution for each material, so that the prediction task has additional structure, for example, increased intensity in one portion of the spectrum predisposes other portions of the spectrum to have lower intensity. This represents the more complex problem of learning features’ and materials properties' relationships and how input features map to multiple labels and we thought it needed a different approach than just using a common GNN.

Toward this vision, we implemented the materials to spectrum (Mat2Spec) framework and we demonstrated for eDOS and phDOS spectra prediction for a broad set of materials with period crystal structures from the Materials Project.

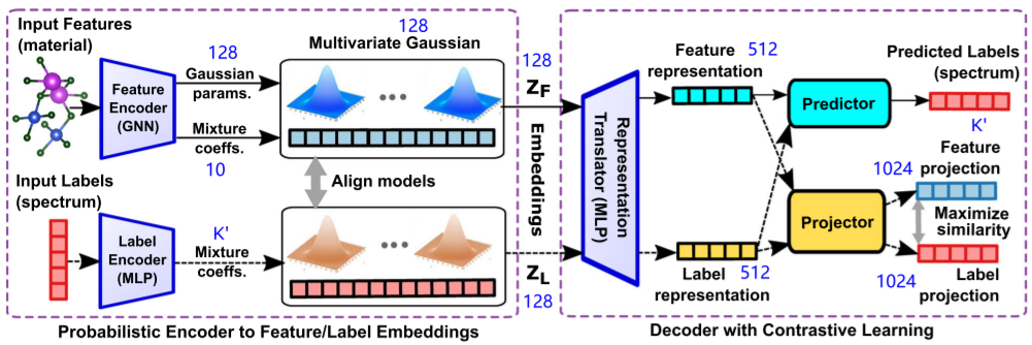

In terms of architecture, at a high level, Mat2Spec uses a GNN, similar to those used in other models, to encode the materials, but it has, in addition, both an encoder and a decoder to capture at best the relationship between structure and its related spectral function. This approach has been used successfully in other fields and it’s probably the first time that it has been used to tackle the spectral functions of materials. In Fig. 1, a scheme of the complete model is represented and some of the details are included in the caption.

Figure 1: The Mat2Spec model architecture. The prediction task of material (Input Features) to spectrum (Predicted Labels) proceeds with 2 primary modules, a probabilistic embedding generator (Encoder) to learn a suitable representation (ZF) of the material and a Decoder trained via supervised contrastive learning to predict the spectrum from that embedding. The solid arrows show the flow of information for making predictions with the trained model, and the dashed arrows show the additional flow of information during model training, where the ground truth spectrum (Input Labels) is an additional input for which the Encoder produces the embedding ZL. Alignment of the multivariate Gaussian mixture model parameters during training conditions the probabilistic generator of the embeddings. Both the input material (Feature projection) and input spectrum (Label projection) are reconstructed to train the model via contrastive learning. The Representation Translator is shared by the prediction and reconstruction tasks, resulting in parallel latent representations that are transformed into the final outputs by the Predictor and Projector, respectively. Note that the output dimension of each component is noted in blue, where K' is 51 for phDOS and 128 for eDOS.

Another difference with previous models is the use of either the Wasserstein distance (WD) or Kullbeck-Leibler loss as loss functions for training our model. These measures quantify the difference in 2 probability distributions and we thought they were more appropriate for the task we are working on. This contrasts with the common use of the standard mean absolute error as a training loss function.

In terms of Mat2Spec’s performance, we benchmark it against the other two models that we consider state-of-the-art in the literature. The first is called GATGNN and it can be considered the most accurate in predicting many single values properties of materials [1]. The second is called E3NN and it represents the first attempt to predict the phDOS of crystal structures with very good accuracy [2]. They all share the same input data with Mat2Spec, which is taken from the Materials Project and computed in a high-throughput DFT fashion.

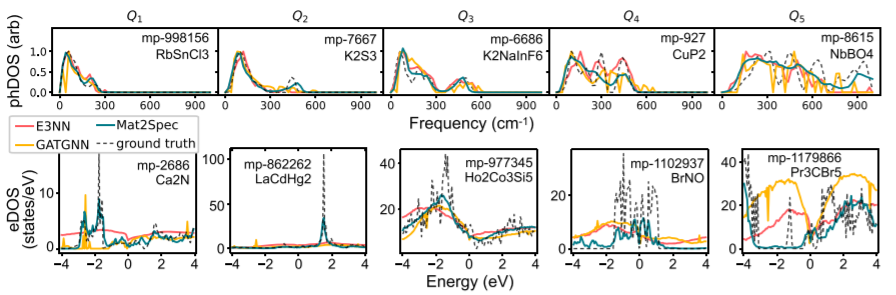

In Fig. 2 a visual benchmarking of the 3 models with the ground truth for both phDOS and eDOS is given, considering 10 different materials and their dos ordered by increasing MAE. Mat2Spec predictions are always closer to the ground truth DOS, especially in the case of the eDOS. The latter is more complex, having high-frequency components the phDOS, and Mat2Spec prediction can at least follow the general trend in the worst-case scenario (i.e. for mp-1179866, Pr3CBr5).

Figure 2: Example phDOS and eDOS predictions in the test set. Ground truth and ML predictions are shown for five representative materials chosen from the 5 quintiles from low MAE loss (Q1, left) to high MAE loss (Q5, right) for both phDOS (top) and eDOS (bottom). From Q1 to Q5 the ground truth phDOS is increasingly complex. For Q1 to Q3, Mat2Spec predicts each phDOS feature, where the other models are less consistent. In Q4, E3NN and Mat2Spec are comparable with their prediction of three primary peaks in the phDOS. In Q5, the presence of substantial density above 600 cm−1 is quite rare, and Mat2Spec is the only model to make the correct qualitative prediction. For eDOS, there is no analogous change in the shape of the eDOS across the quintiles. In Q1 and Q2, Mat2Spec provides the only qualitatively correct predictions. In Q3, each model predicts a smoothed version of the ground truth. In Q4, Mat2Spec prediction is far from perfect but is the only prediction to capture the series of localized states near the Fermi energy. In Q5, each model has qualitatively comparable predictions in the conduction band, but Mat2Spec is the only model to capture the primary structure of the valence band. Mat2Spec’s under-prediction of one localized state makes this one of its highest MAE predictions, which is far lower than the worst predictions from other models. The ability of Mat2Spec to globally capture the qualitative patterns for both phDOS and eDOS leads to its superior performance.

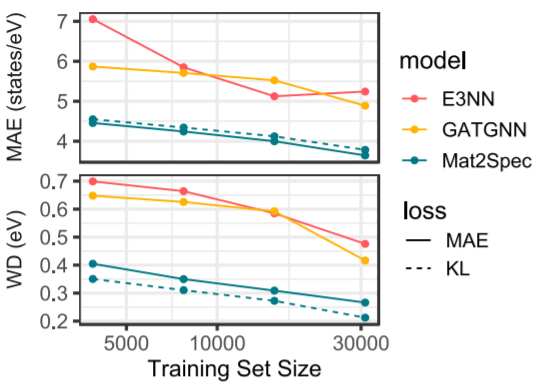

Another way to measure the performance of our model is with respect to the training size. In Fig. 3 it is shown the accuracy with respect to the training size. The result is striking. Mat2Spec reaches slightly higher accuracy than other models but uses 8 times fewer training data. Achieving better results with an 8-fold reduction in data size highlights how the structure of Mat2Spec conditions the model to learn more with less data. Furthermore, this result is of tremendous importance, especially in materials science where small datasets are often the case.

Figure 3. Data size dependence of eDOS prediction. Using a static test set, random down-selection of the train set by factors of 2, 4, and 8 enables characterization of how the prediction loss varies with size of the training set. As expected, prediction loss generally increases with decreasing training size. Using only 1/8 of the training data, Mat2Spec provides lower MAE losses compared to the baseline models that use the full training set.

Motivated by these significant results, we ask ourselves: can we use Mat2Spec to discover new materials? To answer this question, we focused on a class of materials called gapped metals. They are metallic compounds with a band gap close to the Fermi level. This feature makes them similar to doped semiconductors, namely, they can have high conductivity, reach a high Seebeck coefficient, and can be optically transparent. As you may already understand, they have been studied as thermoelectrics and transparent conductors as was reported in Ref. 4 and 5.

We tested our model in the test set first, searching for a band gap in the valence bands. This represents a challenging task as only around 3% of the materials actually have this feature in their dos. We tested Mat2Spec on this binary classification task using a standard measure such as the F1 score. It gets a modest F1 score close to 0.4 but much better than GATGNN and E3NN, which got about 0.3 and 0, respectively.

Next, we turned our attention to a subset of about 8000 materials in the MP that do not have a computed eDOS and we use both Mat2Spec and GATGNN models to predict the eDOS of these materials. The major results that we found is that while GATGNN found only 3 true gapped metals, Mat2Spec is able to find 15 true gapped metals, where true means validated by DFT computations.

In Fig. 4 are the 15 potential gapped metals with their predicted and DFT eDOS. The prediction by Mat2Spec is overall good both in terms of the shape of the DOS and the position and width of the band gap. We were able to identify two classes of materials, oxides, and fluorides, which can be potential gapped metals, having a gap in their eDOS. Interestingly, a couple of fluorides (i.e. mp-1111898, Li2ScCuF6; mp-1111899, Li2GaCuF6) show a quick raising DOS near the Fermi level which could lead to a high Seebeck coefficient. Also, some of these DOS have a large band gap which could lead to optical transparency. While these materials have to be validated by computing their transport and optical properties with accurate approaches, this use case shows the potential of Mat2Spec in first screening a large number of candidates down to a much smaller set where we can use ab initio computation, saving at the same time a huge amount of computational resources.

Figure 4. Discovered materials with VB gaps. Of the 32 predictions of materials with a VB gap according to the results of the Mat2Spec eDOS predictions, the 15 TP predictions are shown. For each material, the eDOS calculated from DFT is shown with the Mat2Spec prediction, and the energy range of the VB gap is also shown. MgAl and LiMg have a VB gap but the inherently low electron density of the material and the persistence of a small but finite eDOS to below -3 eV limits the interest in these materials. LiRAu2 (where R = Nd, Pr, and Yb) have low eDOS considering the presence of heavy elements, although the eDOS does not reach zero in the energy range of interest. Zero density in the energy range of interest is observed in the 10 other materials that fall within 2 families of candidate thermoelectrics. In the family of fluorides with formula Li2AMF6 (where A = Al, Sc, Ga; M = Hg, Cu), each material exhibits a gap of 3–4 eV starting near 0.5 eV below Fermi energy. The eDOS of each material in this family also exhibits a near-gap above the Fermi energy, which motivates their further study for applications such as transparent conductors. A family of oxides with formula ARNb2O6 (where A = Na, K; R = La, Nd, Pr) share a similar eDOS with a VB gap that is 2–3 eV wide starting near 1 eV below Fermi energy.

In conclusion, Mat2Spec is designed to predict spectral functions and this is why it outperforms state-of-the-art models in predicting phDOS and eDOS. Also, with Mat2Spec we were able to screen out thousands of materials to find new potential gapped metals. Finally, the Mat2Spec architecture can address a broader family of problems within and beyond materials science, as of our recently-described opportunity to exploit computational synergies between materials science and other scientific domains [3].

For more details, please check out our paper “Density of states prediction for materials discovery via contrastive learning from probabilistic embeddings” in Nature Communications (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-28543-x).

Reference

[1] Chen, Z. et al. Direct prediction of phonon density of states with Euclidean neural networks. Adv. Sci. 8, 2004214 (2021).

[2] Louis, S.-Y. et al. Graph convolutional neural networks with global attention for improved materials property prediction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 18141–18148 (2020).

[3] Gomes, C. P., Fink, D., van Dover, R. B. & Gregoire, J. M. Computational sustainability meets materials science. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 645–647 (2021).

[4] Kong S, et al, Appl. Phys. Rev. 8, 021409 (2021);

[4] Ricci F, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A, 8, 17579–17594 (2020)

[5] Malyi et al., Matter 1, 280–294 (2019)

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in