Deprived colorectal patients get treated later and died earlier than their affluent counterparts, leading to up to 25 days less being alive and treated within the first year after diagnosis

Published in Cancer

Background

In the past two decades, significant differences in colorectal cancer survival by socioeconomic status have been consistently observed in England. Researchers have investigated this issue, studying factors like age, stage of cancer, and other health conditions which may explain these disparities. While these factors contribute to socioeconomic differences in cancer survival, they don't tell the whole story.

Beyond individual and tumour-related factors, how colorectal cancer is dealt with in the healthcare system might be playing a crucial role. This includes treatment methods, and time between diagnosis and treatment, which vary greatly between individuals, despite the National Health Service (NHS) being a universal healthcare system. While researchers have studied regional differences in treatment among colorectal cancer patients, a significant gap in knowledge remains. We still don’t fully understand the extent to which socioeconomic deprivation affects the likelihood and timing of receiving treatments. This already complex question is made even more challenging to address by the unfortunate reality that some patients might not survive long enough to undergo these treatments.

Understanding these nuances is not only essential for patients and their families, but also for healthcare professionals and policymakers. By unravelling the complex interactions between socioeconomic status, treatment disparities, and survival rates, we can pave the way for a healthcare system that offers equal opportunities and support for every colorectal cancer patient, regardless of their background or circumstances.

What did we investigate?

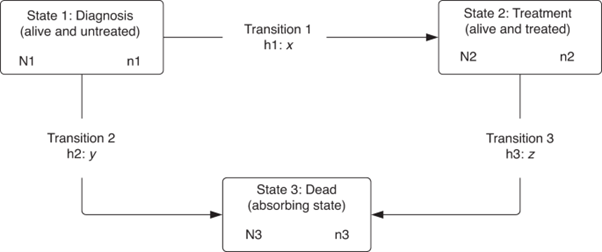

In our research, we studied people in England who were diagnosed with colon or rectal cancer between 2012 and 2016. We wanted to understand how long it took for these patients to receive their first treatment (surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy) within the first year after diagnosis. We also considered the sad possibility that some patients might have passed away before they could get any treatment. We looked at three situations that could happen within the first year after diagnosis: patients waiting for treatment, patients who received treatment and were still alive, and patients who unfortunately passed away. To make sense of all this information, we used a specific method called a 'multistate model' to figure out the chances of patients moving between these situations and how many days they stayed in each situation. We also compared these numbers based on the social and economic backgrounds of the patient’s area of residence, which we call 'deprivation'.

What did we find?

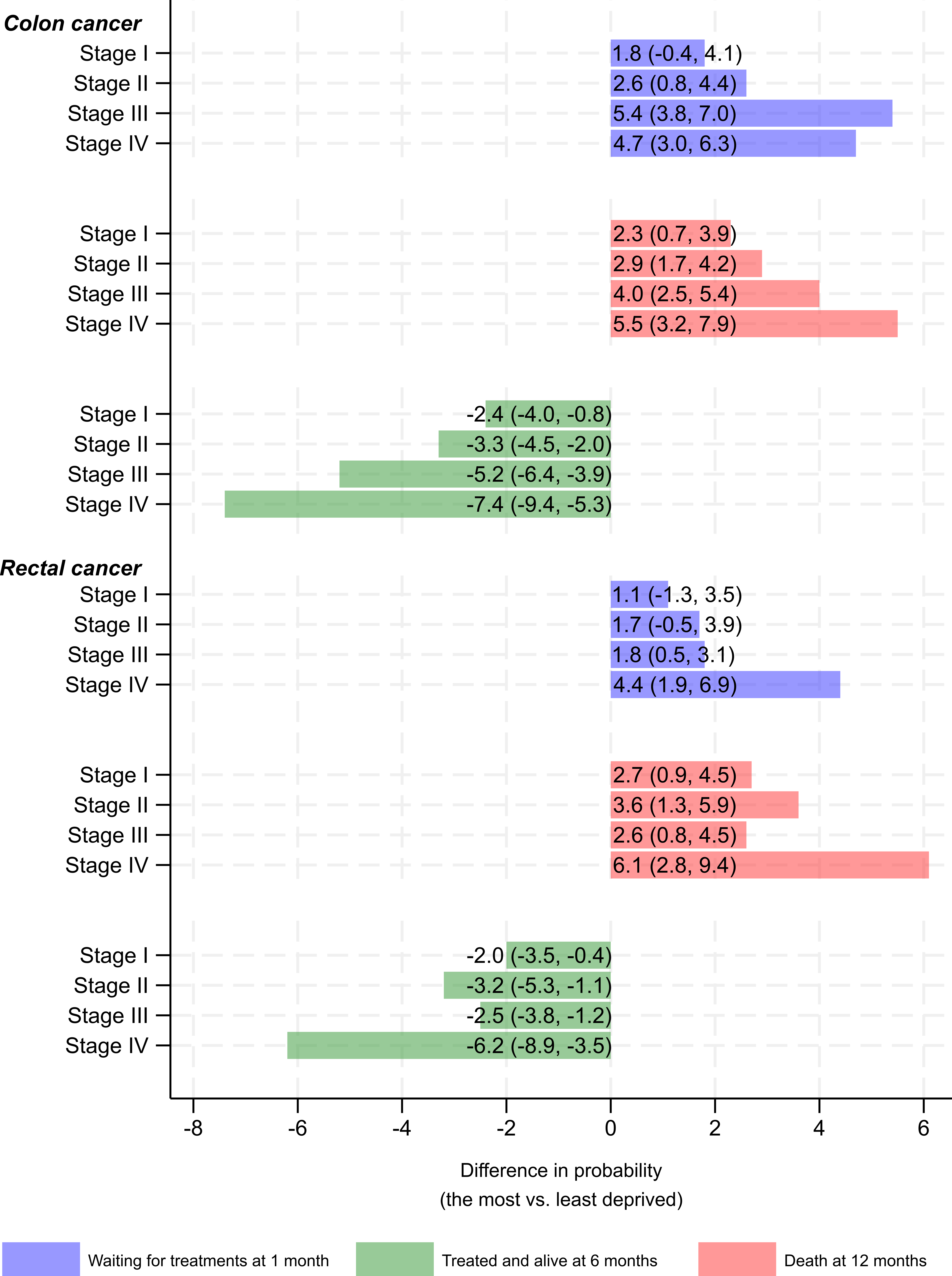

We found that, even after considering factors like age, sex, and other health conditions, there are still significant differences in how patients are treated based on the deprivation of the area they live. Patients from poorer backgrounds, those who lived in the 20% most deprived areas in England, had a harder time getting treatment and were more likely to die earlier, in all stages of their cancer. For example, within six months of diagnosis, the most deprived patients had a 2.4% to 7.4% lower chance of being alive and treated in colon cancer cases and a 2.0% to 6.2% lower chance in rectal cancer cases.

(x axis represents the difference in probability of staying at three states at different time points after cancer diagnosis, comparing the most deprived to the least deprived)

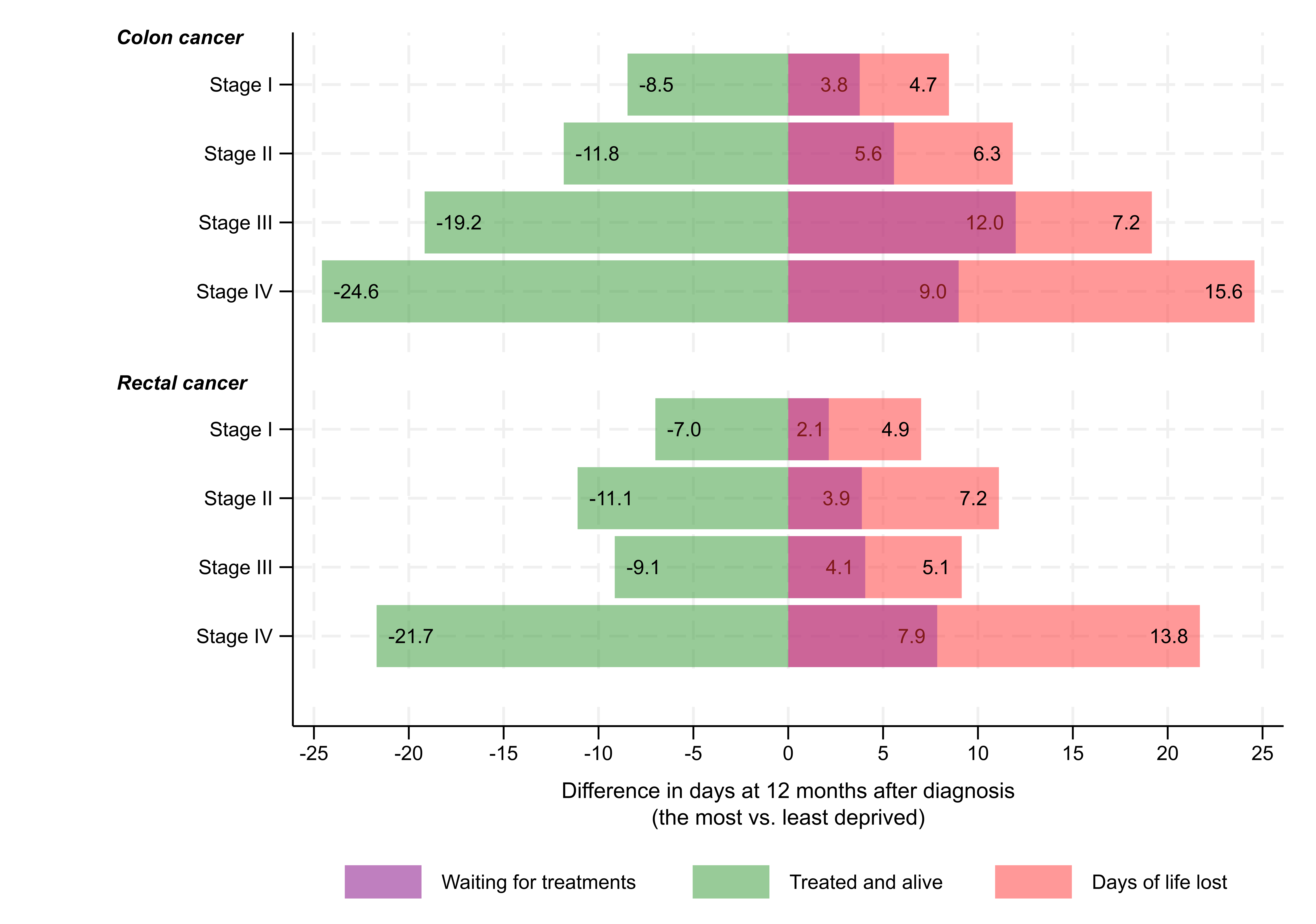

This means they not only spent fewer days alive after getting treatment, but also had more days without any treatment. Past one year after diagnosis, for example, in stage IV colon cancer, the disparity in days spent being alive and treated was notable: 169.3 days for the least deprived versus 144.7 days for the most deprived, leading to almost 25 days difference. These 25 days include 9 days delayed treatment, and an average of 16 days earlier death.

Why are these findings important?

Our findings indicated that there are differences in how patients from rich and poor areas are treated for colorectal cancer, and this could be a big reason why some patients don't survive as long as their less deprived counterparts. We need to understand why these treatment differences happen and make changes in our healthcare system to fix them. This is especially important in the NHS. Considering all the challenges the NHS faces, it's crucial to look closely at how medical resources are given to the poorest communities. Currently, resources (funding) allocations are based on population in each integrated care board (ICB, previously clinical commissioning group, CCG), but the adjustment for inequalities and unmet needs in current formulae may not be sufficient. In addition, other sources of funding, such as local authorities and charities, may vary based on socioeconomic status of the areas. By studying these issues and making informed changes, we can work towards ensuring that everyone, no matter where they come from, has a fair chance at getting the right care and surviving cancer.

Follow the Topic

-

British Journal of Cancer

This journal is devoted to publishing cutting edge discovery, translational and clinical cancer research across the broad spectrum of oncology.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in