Development of a short HIV stigma scale

Published in Healthcare & Nursing, Social Sciences, and Sustainability

Introduction

The role out of efficient HIV treatment has had a tremendous impact on HIV-related mortality and morbidity. From being a lethal disease, HIV infection is now considered a long-term manageable condition with normal life expectancy where treatment is available.

Based on Goffman's (1974) definition, stigma is a social process involving labelling and stereotyping leading to loss of status and discrimination for the person experiencing the stigmatising feature. Stigma has been a prominent feature of HIV already since the beginning of the pandemic and has been an obstacle to prevention, diagnosis and treatment ever since. In our work, we focus on stigma from the individual perspectives of people living with HIV and build on the HIV stigma framework developed by Earnshaw and Chaudoir (2009). According to the HIV stigma framework, HIV stigma consists of three different mechanisms enacted stigma (the stigmatising and discriminating actions one experiences from the environment), anticipated stigma (the actions one expects from the environment if one's HIV infection becomes known) and internalised or self-stigma (negative feelings against oneself because of having HIV).

Working in Sweden, we identified a need to systematically map and monitor HIV stigma among people living with HIV in Sweden. To fulfil this need, we drew upon an inventory of existing HIV stigma measures made by Earnshaw and Chaudoir (2009). From this inventory we selected the 40-item HIV Stigma Scale (Berger et al., 2001) to translate, adapt and test in the Swedish context (Lindberg et al., 2014). The HIV Stigma Scale covers four domains of HIV stigma: personalised stigma (enacted), disclosure concerns (anticipated), concerns with public attitudes (anticipated) and negative self-image (self-stigma). Each of the 40-items is answered on a four-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). The individual responses to all items in a domain are summarised to form a domain score. Higher scores mean higher levels of experienced stigma. We translated and tested the scale and showed that it was valid and reliable to use in a Swedish context. However, this measure is quite lengthy and to be able to include the aspects of HIV stigma in broader surveys of the life-situation of people living with HIV and to decrease the item burden when wanting to monitor HIV stigma with repeated measurements over time, we decided to develop a short version of the scale which I will describe in brief as follows.

The paper

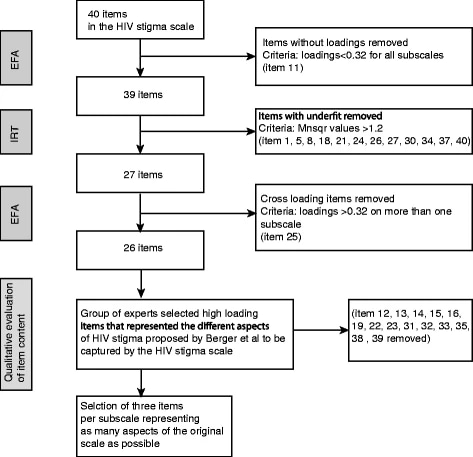

Reusing the data from our testing of the 40-item scale (Lindberg et al., 2014), we applied a three-stage process to reduce the number of items. 1) Removing items with underfit, 2) Removing cross-loading items and 3) Keeping as many aspects as possible, see Figure 1. This process resulted in a suggested 12-item scale with three items from each of the four aspects from the original scale.

Figure 1. Visualisation of the item reduction process going from 40 to 12 items. Reproduced from the original publication featured here.

We then took the suggested 12-item scale forward by testing it as one part of a nationwide survey of the life situation of people living with HIV in Sweden (Zeluf-Andersson et al., 2019). The study included a diverse sample of 1096 participants of which 880 had complete data available from the 12-item scale. To test the construct validity, we divided the sample into two groups and analysed the data from the first group with exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and the data from the second group with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The scale's internal consistency was tested by calculating Cronbach’s α for each of the four domain subscales.

The results showed that we succeeded to cover most of the aspects included in the original scale and that the scale showed acceptable properties. However, three of the four domain scales showed floor or ceiling effects. This means that many participants (between 22 and 28%) gave the highest or lowest possible rating of the respective domain scale in focus, which makes those scales less sensitive to detect changes over time or differences between groups.

Conclusion

We concluded that the 12-item Short HIV Stigma Scale that was developed, has comparable properties to the full-length scale and may be used when a shorter instrument is needed.

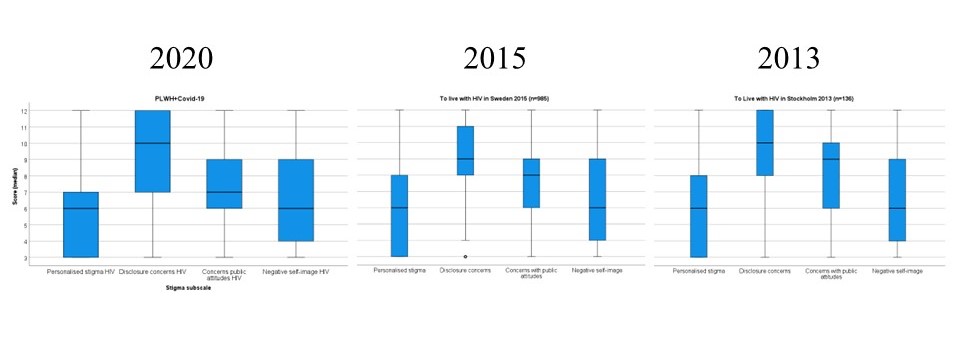

Continued work, experiences of HIV stigma in Sweden

Sweden was one of the first countries reaching the WHO UNAIDS 90-90-90 goal, later upgraded to the 95-95-95 goal. This means that at least 95% of people living with HIV have received their diagnosis and that at least 95% of those receiving treatment and of those in turn, at least 95% have successful outcomes of their treatment in the form of viral suppression ("undetectable viral load" which means extremely low or undetectable HIV levels in the blood; U=U - Undetectable=Untransmissible). One then also would expect that this would decrease the stigma attached to HIV. However, when we look at data that we have collected with the 40-item HIV Stigma Scale (2013; Lindberg et al., 2014) or the 12-item Short HIV Stigma Scale (2015 (Nilsson Schönnesson et al., 2024) and 2020 (Reinius et al., 2023)), as illustrated in Figure 2, we do not see any tendencies for decreasing stigma in people living with HIV in Sweden. The exeption is the conserns with public attiudes, where a slight decreasing tendency can be seen over time. A majority of the participants still have concerns revealing that they have HIV and many exhibits negative attitudes towards themselves related to having HIV.

Figure 2. HIV stigma levels in three different cohorts people living with HIV in Sweden collected 2013, 2015 and 2020 (comparison unpublished). Each stigma domain subscale could have a score ranging from 3-12, higher scores mean higher levels of experienced stigma.

Impact

The article where we describe the development of this 12-item Short HIV Stigma Scale receives a lot of attention; I get many questions from students and researcher colleagues around the world interested in using the scale for their work and it is one of the highly cited articles from the Health and Quality of Life Outcomes journal. Although it is unacceptable that people living with HIV still experience a great deal of stigmatisation, I am happy and proud that our work is valued and contributes to shed light on the life situation of people living with HIV in different contexts around the globe.

References

Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.10011.

Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1160–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3.

Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. 1974. New York, NY: J. Aronson.

Lindberg MH, Wettergren L, Wiklander M, Svedhem-Johansson V, Eriksson LE. Psychometric evaluation of the HIV stigma scale in a Swedish context. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114867. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0114867.

Nilsson Schönnesson L, Dahlberg M, Reinius M, Zeluf-Andersson G, Ekström AM, Eriksson LE. Prevalence of HIV-related stigma manifistations and their contributing factors among people living with HIV in Sweden - a nationwide study. BMC Public Health 2024;(1):1360. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18852-9.

Reinius M, Svedhem V, Bruchfeld J, Holmström Larm H, Nygren-Bonnier M, Eriksson LE. COVID-19-related stigma among infected people in Sweden; psychometric properties and levels of stigma in two cohorts as measured by a COVID-19 stigma scale. PLoS ONE 2023;18(6):e0287341. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287341.

Zeluf-Andersson G, Eriksson LE, Nilsson Schönnesson L, Höijer J, Månehall P, Ekström AM. Beyond viral suppression: the quality of life of people living with HIV in Sweden. AIDS Care 2019;31(4):402–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2018.1545990.

Follow the Topic

-

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes

This is an open access, peer-reviewed journal offering rapid publication and wide diffusion in the public domain of high-quality articles in the field of Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL).

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Refining the EQ-HWB instrument: psychometric evidence and methodological advances

The EQ Health and Wellbeing (EQ-HWB) tool is a new, experimental instrument by the EuroQol Group designed to capture a broader range of outcomes beyond traditional health-related quality of life measures. Designed for use in patients, social care users and caregivers, the EQ-HWB has two versions: a long-form profile measure and a 9-item short form (EQ-HWB-9), which is a preference-based measure, suitable for the evaluation of health, public health and social care interventions. Since the publication of the EQ-HWB in 2022, several smaller refinements have been proposed to improve the instrument’s usability and performance. These include modifications to item order, wording, response levels and layout. This special collection at Health and Quality of Life Outcomes offers a timely opportunity to share scientific evidence on the impact of these modifications, contributing to the finalisation of the instrument. The collection will be of broad interest to the health outcomes research community, particularly those involved in the development and validation of measures for health and caregiving.

We invite submissions on a wide range of topics, including:

-Qualitative and quantitative psychometric testing of EQ-HWB and EQ-HWB-9 modifications across diverse settings, populations and languages, including general population samples, social care users, caregivers and patients with long-term conditions.

-Methodological studies comparing the psychometric performance of proposed EQ-HWB and EQ-HWB-9 modifications (e.g. item order, wording, response scales, layout).

-Empirical studies supporting the evidence base for the EQ-HWB and EQ-HWB-9 and informing future instrument development.

Please contact the special collection editors directly to determine whether your topic idea is suitable for the collection.

We welcome contributions from researchers, clinicians and methodologists working across all medical fields, as well as in health outcomes research, social care and psychometrics.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3, Good Health and Well-Being.

All submissions in this collection undergo the journal’s standard peer review process. Similarly, all manuscripts authored by a Guest Editor(s) will be handled by the Editor-in-Chief. As an open access publication, this journal levies an article processing fee (details here). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in