Diamonds are forever mirrors

Published in Physics

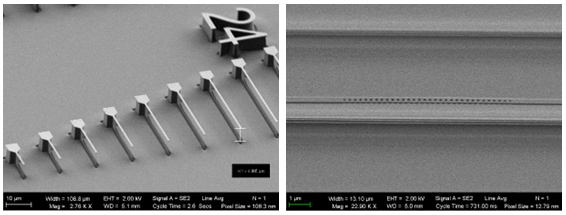

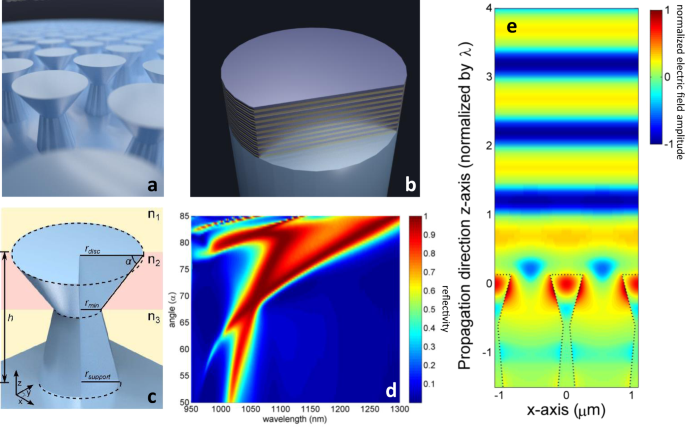

Our research typically concerns the use of diamond for quantum technology, that is, we build prototype information processing devices which exploit the unique laws of quantum physics. One of our goals is to control light-emitting diamond defects, the origin of colored versions of the rock. Our devices allow the defects to emit individual particles of light, that is, single photons, with carefully engineered properties. Some devices include diamond waveguides (Fig. 1, left) which direct light, and “photonic crystal nano-beam” resonators (Fig. 1, right) which enhance the emission of light from defects.

Figure 1. Free-standing diamond nano-structures. Note the scale bars.

In the process of developing our device fabrication techniques, we realized they could be used to create arrays or distriutions of nanoscopic diamond structures across a large surface area. This would allow us to create a surface that offered high-resolution control of the intensity of light that was reflected from it. This technique has been investigated for decades in other materials, like glass, to produce anti-reflection surfaces, which find applications in imaging and laser beam manipulation, for instance.

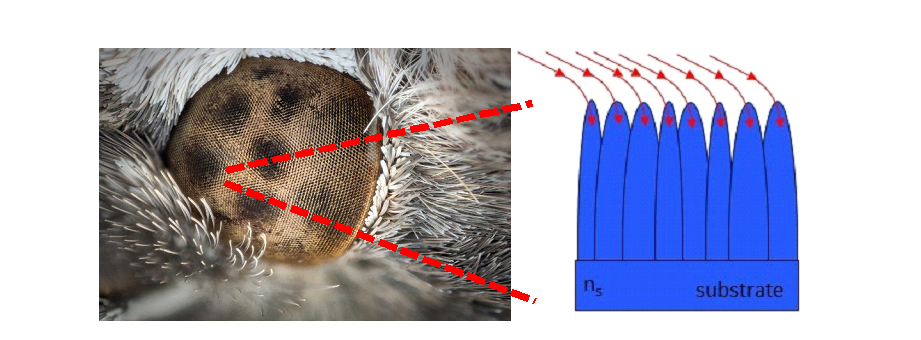

Anti-reflection surfaces like this have been referred to as “moth-eye” surfaces, owing to its inspiration from the structured nature of a moth’s eye (Fig. 2). These surfaces comprise a distribution of pillars with nanoscopic widths that taper outwards with depth, leading to a slow transition between the optical properties of air to that of the underling optical material (ns, substrate).

Figure 2. Moth eye-inspired tapered nano-pillars used in anti-reflection surfaces.

Rather than suppressing a reflection, we considered the possibility to fabricate a highly reflective mirror from single-crystal diamond. It begs the question: what is special about a diamond mirror? Diamond is known to have the highest thermal conductivity at room temperature (2200 W/K⋅m) which, including its mechanical hardness and chemical resistance, underlies several of its uses in industrial applications. In other words, if diamond gets hot, it will dissipate the heat and not break down. Furthermore, high-quality diamonds are free of defects that absorb light and convert light energy into heat. Our thought was that a single-crystal diamond mirror created by etching may withstand continuous irradiation of high-power laser light. This would be beneficial as high-power continuous-wave lasers find uses in applications ranging from manufacturing and welding to military, communications, mining, and more.

Conventional highly reflective mirrors are made from layers of non-crystalline coatings that readily generate heat when irradiated with continuous-wave laser light. Such mirrors typically require expansion of the laser beam, which adds complexity and restricts scope as well as utility of the mirror. Thus, we were motivated to create a compact, nano-structured, diamond mirror of high reflectivity that could handle high continuous-wave laser powers.

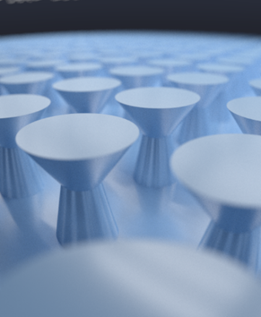

After performing some numerical simualtions, we realized it would be possible to create a mirror with a two-dimenaional array of “golf tee”-like columns, as imagined in Fig. 3.

Figure 3. Artist-rendered vision of the diamond suface. Image credit: P. Latawiec.

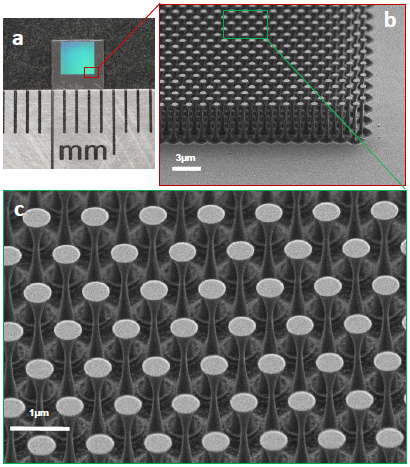

We then proceeded to create the mirror on a polished diamond slab, creating arrays of golf tees over a nine square millimeter surface area (Fig. 4). This surface area was chosen as it accomodates the width of a typical laser beam and uses only a small amount of diamond.

Figure 4. Electron microscope images of the etched diamond mirror surface at different magnifications.

At this point, we were eager to measure the reflectivity of the mirror. Carefully taking into account any imperfections in our Harvard laboratory apparatus, we measured an absolute reflectivity of 98.9%, with an uncertainty of 0.3%, at a laser wavelength of 1.064 micrometers, one that is typically used in applications.

Next, we reached out to the Laser Technology and Analysis Branch of the U.S. Navy in Dahlgren, Virginia for high-power testing. After some initial testing, they recommended we head to the Pennsylvania State University Applied Research Laboratory, Electro-Optics Center, in Freeport Pennsylvania as they had the abilities to perform tests with higher laser powers. There we discovered that our mirror withstood laser irradiation using 10 killowatts of laser power without damage (Fig. 5, left). For comparison, we repeated the testing using a standard off-the-shelf mirror, finding it was damaged with this much power (Fig. 5, right). We encourage the reader to see the thermal and optical videos of the damage tests which are included in the Supplementary Materials of our published manuscript.

Figure 5. Diamond mirror on mount at the Penn State EOC (left). Damaged standard off-the-shelf mirror after the laser testing (right). Image credit: S. DeFrances.

Upon reflection of our work—no pun intended—we are intrigued by the fact that the same diamond crystal that we use for emitting single photons has been used to control the direction of more than fifty sextillion photons per second (one sextillion is a one with 21 zeros after it). Note that, we in fact did not determine the laser damage threshold power for our diamond mirror. Thus, we encourage any reader with a suitable laser to reach out to us to resolve this now lingering question.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in