Echinoderms as a paradigm to understand how genome organization shapes body plans and their evolution

Published in Ecology & Evolution and Genetics & Genomics

Introduction

Echinoderms are a group of animals that includes sea urchins, sea stars, sea cucumbers, brittle stars and sea lilies. They are the closest phylum to chordates, a group that includes vertebrates such as us humans. While echinoderm larvae show bilateral symmetry, their adult forms have a pentaradial symmetry, that is, their body parts are arranged in five (or multiples of five) sections around a central axis. Animal morphology is dependent on its spatiotemporal control of gene expression, i.e. where, when and which genes are turned on in the body and to what extent. In order to find out how species build their distinct embryonic and adult body plans, from sponges and comb jellies to sea urchins and humans, one needs to look at how each species' genome and genes are regulated.

The first genome of an echinoderm, a sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, was released in 2006, only a few years after the human genome project was declared complete in 2003. Sea urchins have a rich history of being used for biological research from Theodor and Marcella Boveri’s research into chromosomes (early 19th century), through Eric Davidson’s establishment of the field of gene regulatory network in context of sea urchin development (ca. 2002) to recent advances into the similarities between vertebrate brain and the sea urchin nervous system (2025). For many of these research endeavours, a strong molecular toolkit including a reference genome is needed.

To start with, our work presents two updated assemblies of reference genomes for two echinoderm species: the purple sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) and the bat star (Patiria miniata). These are both Pacific echinoderm species, and both have extensive research done on their development.

Why make new assemblies?

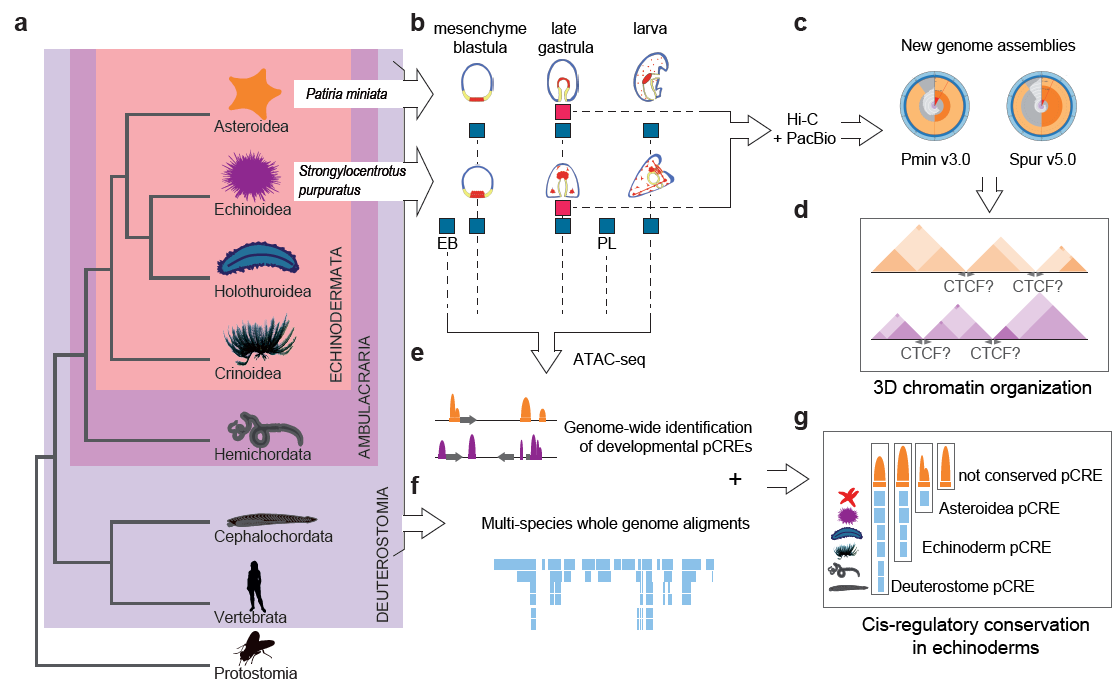

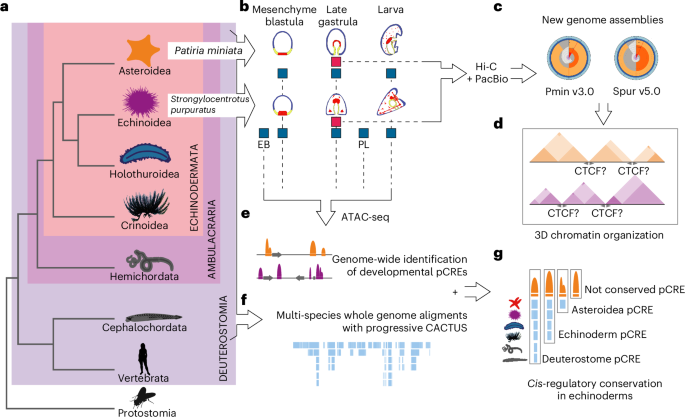

Even though both species had reference genomes sequenced, better assemblies were necessary. Since 2006 there have been a number of attempts to improve the purple sea urchin genome, many of which were fairly successful and resulted in genomes that could provide information on the DNA sequence and the gene structures. On the other hand, the bat sea star genome had only a single draft genome prior to our work. Unfortunately, the genome assemblies for both species were highly fragmented, and lacked sufficient evidence to characterize the precise genomic locations of many genes. The scaffolds, genome regions representing sequenced pieces of a chromosome, were too short, and there were cases where researchers could not confidently tell whether certain genes were on the same chromosome as they were on different scaffolds. The two new assemblies approach chromosome level, and most of each assembly is contained within its largest scaffolds. This was achieved with the advances in 3D genome organization methods such as HiC and long read sequencing such as PacBio. HiC sequencing can reveal which regions of DNA lie next to each other, both within a single chromosome and across different chromosomes. PacBio allows the sequencing of larger pieces of DNA at once without needing to break it apart like short-read approaches. This allowed us to vastly improve the completeness and decrease fragmentation for both genome assemblies (see Figure1 c). Moreover, a great number of transcriptomic samples, along with the NCBI RefSeq pipeline, allowed us to annotate the new assemblies with improved precision on the locations and the structure of genes.

Why look at how the genome is organized?

Chromatin folding plays an essential role in gene regulation by allowing long range interactions between different regions of the DNA. Echinoderms have a unique phylogenetic position (see Figure1 a). They belong to the Ambulacraria clade, together with the hemichordate worms - a sister group to chordates. Just like vertebrates, they are deuterostomes, and yet they are non-vertebrates. Thus, it could be argued that they occupy an intermediate position between different groups of organisms, and share similarities with both vertebrates and other non-vertebrates. In vertebrates, the CTCF protein plays a pivotal role in organizing DNA into chromatin. It orchestrates looping and helps in forming chromatin topologically associating domains (TADs), and its orientation is very important for its function. However, in non-vertebrates such as the fruitfly, CTCF does not play such an important role in 3D chromatin organization as they use other lineage specific proteins. We wanted to look into the role of CTCF in echinoderms (see Figure1 c,d). Despite the evolutionary closeness to vertebrates and the presence of CTCF gene orthologs, our work shows that echinoderms do not seem to employ CTCF in the same way as vertebrates. For instance, CTCF motifs are enriched in only around half of the echinoderm TAD boundaries, and it does not have the characteristic motif orientation that is found in vertebrates. This suggests that chromatin loops and TADs are more similar to non-vertebrates lineages than to vertebrates since they do not use CTCF as the crucial component, potentially using other structural proteins for this function. Many animal species show TADs and other types of chromatin compartmentalization, even those that do not have CTCF, so CTCF use for long range DNA interactions is likely a vertebrate novelty.

Why are conserved regulatory elements important?

We generated and looked at chromatin accessibility (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing) data at different developmental time points that we used as putative Cis-Regulatory Element (pCRE) proxies (see Figure1 b, e). CREs are adjacent regions of DNA that control genes, via (for example) the binding of transcription factors (TFs). We performed multi-species genome comparisons including multiple echinoderm species, as well as species from other phyla such as humans, the zebrafish (Danio rerio), the gar (Lepisosteus oculatus), the acorn worm (Saccoglossus kowalevskii) and the sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis), to identify conserved regions (see Figure1 f, g). Many pCREs were shared only between closely related species, which many previous studies describe as having a high turnover rate in regulatory regions. However, some pCREs were conserved between very distant echinoderm lineages or even across different phyla (i.e. transphyletically conserved). Many of these conserved pCREs were found mostly at a late gastrula stage, which shows high conservation of morphological features and gene expression in many animal lineages. Thus, it is likely that these pCREs regulate core developmental programs shared among deuterostomes. This shows that certain developmental processes are so highly conserved that even the DNA sequences regulating them are constrained. Elucidating the reasons for such constraints could reveal core, defining features of animal evolution.

Conclusion

Thus, we* have made significant steps further to uncover the principles of evolution, and how these principles lead to the diversity of species and their genomes. This could potentially allow us to predict how evolution may continue to function.

*This work has been possible thanks to the amazing people that were part of this team effort: Marta Magri, Danila Voronov, Saoirse Foley, Pedro Manuel Martínez-García, Martin Franke, Gregory A. Cary, José M. Santos-Pereira, Claudia Cuomo, Manuel Fernández-Moreno, Marta Portela, Alejandro Gil-Galvez, Rafael D. Acemel, Periklis Paganos, Carolyn Ku, Jovana Ranđelović, Maria Lorenza Rusciano, Panos N. Firbas, José Luis Gómez-Skarmeta, Veronica F. Hinman, Maria Ina Arnone and Ignacio Maeso.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Ecology & Evolution

This journal is interested in the full spectrum of ecological and evolutionary biology, encompassing approaches at the molecular, organismal, population, community and ecosystem levels, as well as relevant parts of the social sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning of global peatlands

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jul 27, 2026

Understanding species redistributions under global climate change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in