Ecological Restoration Benefits Communities-But How Much?

Published in Earth & Environment and Ecology & Evolution

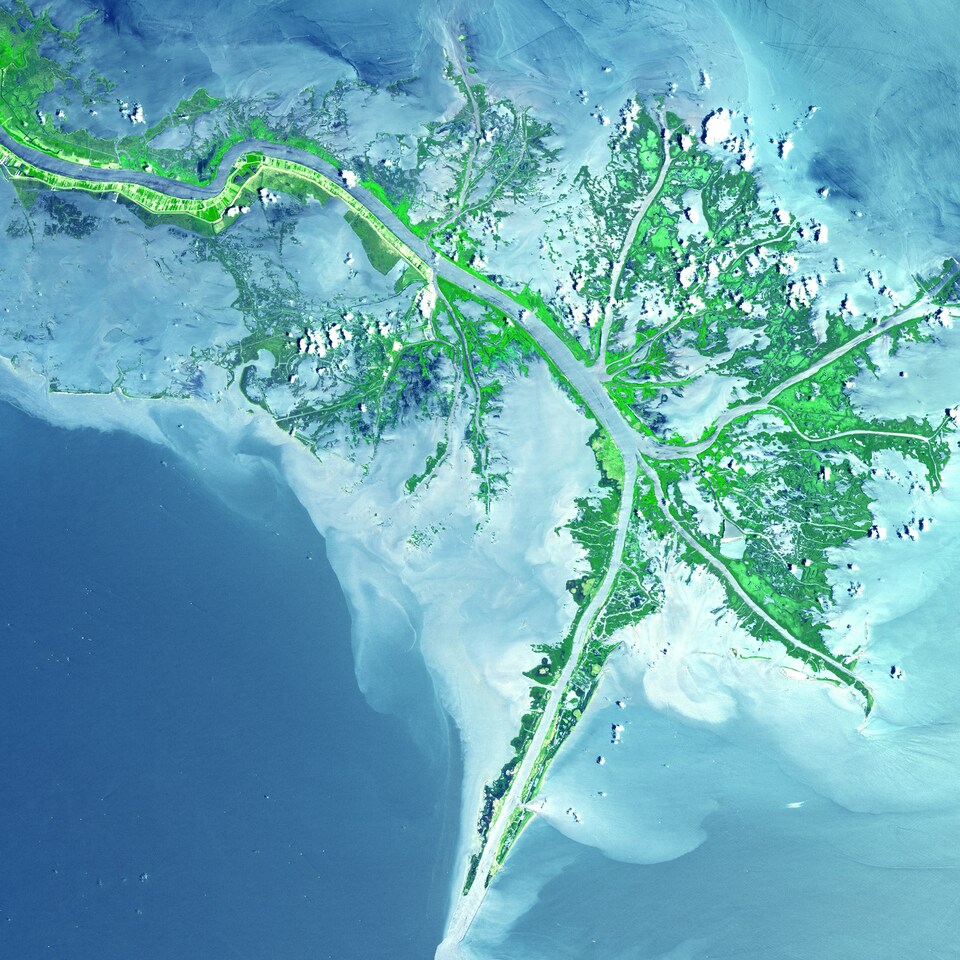

Half Moon Reef, a 54-acre restored oyster reef in Texas’ Matagorda Bay, is a large-scale restoration project that cost around $4 million. Only a couple years after restoration, it generated $1.2 million in annual economic activity, $465,000 in payments to workers every year, a fivefold increase in oyster size, and an increase in biodiversity of around 40%.

Since the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, billions of dollars have been invested in ecological restoration projects like this one across the Gulf of Mexico. While Half Moon Reef has documented impressive benefits, many other similar projects lack information about social and economic outcomes.

This is unfortunate, given the wide range of benefits that restoration and other nature-based solutions can provide to communities. These can include reduced coastal erosion and coastal storm damages, greater economic investment in tourism and recreation, increased opportunity for fishing and hunting, reduced water treatment costs, and contributions to climate stability through carbon storage.

Why does the monitoring of social and economic outcomes lag behind the tracking of ecological and physical outcomes? The methods for assessing social and economic outcomes are less established, and metrics vary—making it difficult to compare projects’ results or get a comprehensive perspective. Managers also lack experience and support for conducting these measurements and modeling.

The lack of information makes it difficult to evaluate investments, improve them, target benefits to certain communities, and create success-based financing models (i.e., pay-for-performance, environmental performance bonds).

What can be done to address these shortcomings? We’ve gleaned useful insights from a multiyear project run by Duke University's Nicholas Institute for Energy, Environment & Sustainability; the Harte Research Institute; and The Nature Conservancy, in partnership with regional stakeholders, relevant federal and state agencies, and technical experts. The project’s goal was to expand monitoring and evaluation of social and economic outcomes for coastal restoration projects in the Gulf of Mexico.

Here are two immediate key steps:

-

Expand the types of social and economic measures that are requested by funders and monitored by projects. This will require going beyond the measures identified in the Natural Resource Damages Act (NRDA) Measurement and Adaptive Management guide. For example, our project identifies metrics related to property value, food security, and mental health that are not included in the widely used NRDA guidance.

-

Increase measurement consistency by using the metrics identified through our project. This will make it possible to track progress not only at the project scale but also at the regional scale, and will enable comparison across projects to see what is working well and what is not.

Three additional key steps will require more investment from programs such as the National Science Foundation Gulf Research Program and RESTORE:

1. New data collection and data disaggregation are needed to enable measurement of many social and economic outcomes. For example, to accurately gauge the health impacts of restoration projects, health data would need to be collected regularly and coded with reference to environmental conditions—and would need to be available at a high-enough resolution to spatially link cause and effect. (Such shifts would make it possible to track, for example, a reduction in incidences of respiratory distress that could be connected to algal blooms.) Water treatment cost data would need to be collected from water utilities and municipalities. And recreational fishing data would need to have spatial resolution fine-grained enough to be useful for assessing local restoration project impacts.

2. Many social and economic outcomes require regional-scale measurement of cumulative impacts rather than project-scale measurement. This in turn requires different methods, experts, and funding to implement the measurement. For example, economic implications of restoration-driven increases in tourism or declines in pathogen-related health impacts would likely be regional effects that would require evaluating cumulative effects across many projects.

3. A different approach is needed to evaluate distribution of outcomes across affected communities. It’s common to rely on aggregated or average data on economic activity, risk reduction to property, or health impacts—but this doesn’t illuminate how a project has benefited different parts of a community. To prioritize issues of equity and justice, it is critical to collect data about who is being affected and how. Who is landing newly created jobs, for example? Whose homes are seeing lower risks? Whose health is improved?

Billions of dollars have been spent on ecological restoration in the Gulf of Mexico in the wake of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill—and now we need to invest attention and resources in evaluating the outcomes. Luckily, there is a clear path forward: steps that can help us understand and learn from these projects’ effects on the environment as well as on the well-being of the people who live near and rely on the Gulf.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Holocene hydroclimate

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in