Enhanced tumor visualization in patients using fluorescence lifetime imaging and indocyanine green

Published in Biomedical Research

Cancer surgeries currently rely on the ability of surgeons to touch and feel tumors to decide where to cut tissue. There are currently no reliable tools for distinguishing tumors from healthy tissue in the body, so that tumors can be removed as completely as possible without affecting normal structures and function. As a result, excess residual tumor is often left behind after surgery. Further, the presence of the excess tumor is only known from pathology reports days after the surgery. Incomplete tumor removal invariably leads to patients having to come back for repeat surgery, and increased recurrence of cancer, causing significant burden on the patients and the healthcare system.

On the other side of the spectrum, to ensure complete removal, surgeons will often remove excess healthy tissue surrounding the tumor, leading to impaired function and appearance, morbidity, and stress, and requiring expensive and time-consuming rehabilitation to regain normal function. For example, removal of normal tissue in oral cancer can lead to speech impairments that require speech therapy.

To help address these issues, many different technologies have been explored for surgical guidance, including fluorescence imaging, advanced microscopy techniques and Raman scattering. Despite over two decades of effort, though, no imaging technology to date has proved effective enough for widespread clinical adoption.

Fluorescence imaging is a promising technology for tumor visualization, since it uses non-ionizing light, is easier to operate and lower cost than MRI or PET and allows tumor visualization from the macroscopic to the microscopic level. The traditional approach to fluorescence imaging relies on developing fluorescent dyes that target cancer-specific molecular expression. However, the development of such dyes has been a challenging problem. Dyes often accumulate in normal tissue besides the cancer. Also, even when tumor specific, there is significant variation in molecular expression within and across different cancer types. Therefore, most existing fluorescent probes are effective only for one or two types of cancer. This makes clinical translation even more challenging due to the high cost of developing new compounds for each cancer type.

Our lab takes a different approach to standard fluorescence imaging. Instead of relying on novel dyes that target cancer, we rely on changes to the property of the light emitted by tissue: in particular, the fluorescence lifetime (also called half-life). Fluorescence lifetime refers to the average time for a fluorescent molecular to decay following excitation by a light pulse. In earlier work, we found that tumors in mice injected with an FDA-approved dye, indocyanine green (ICG), had a longer fluorescence lifetime compared to normal tissue. The longer lifetime allowed the separation of tumor from normal tissue with high accuracy. We subsequently demonstrated that the lifetime of a fluorescent probe targeted towards the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) can accurately delineate head and neck tumors in surgical resection specimens from head and neck cancer patients. However, this probe is not yet FDA approved and is not universally applicable since EGFR is not expressed in all tumor types.

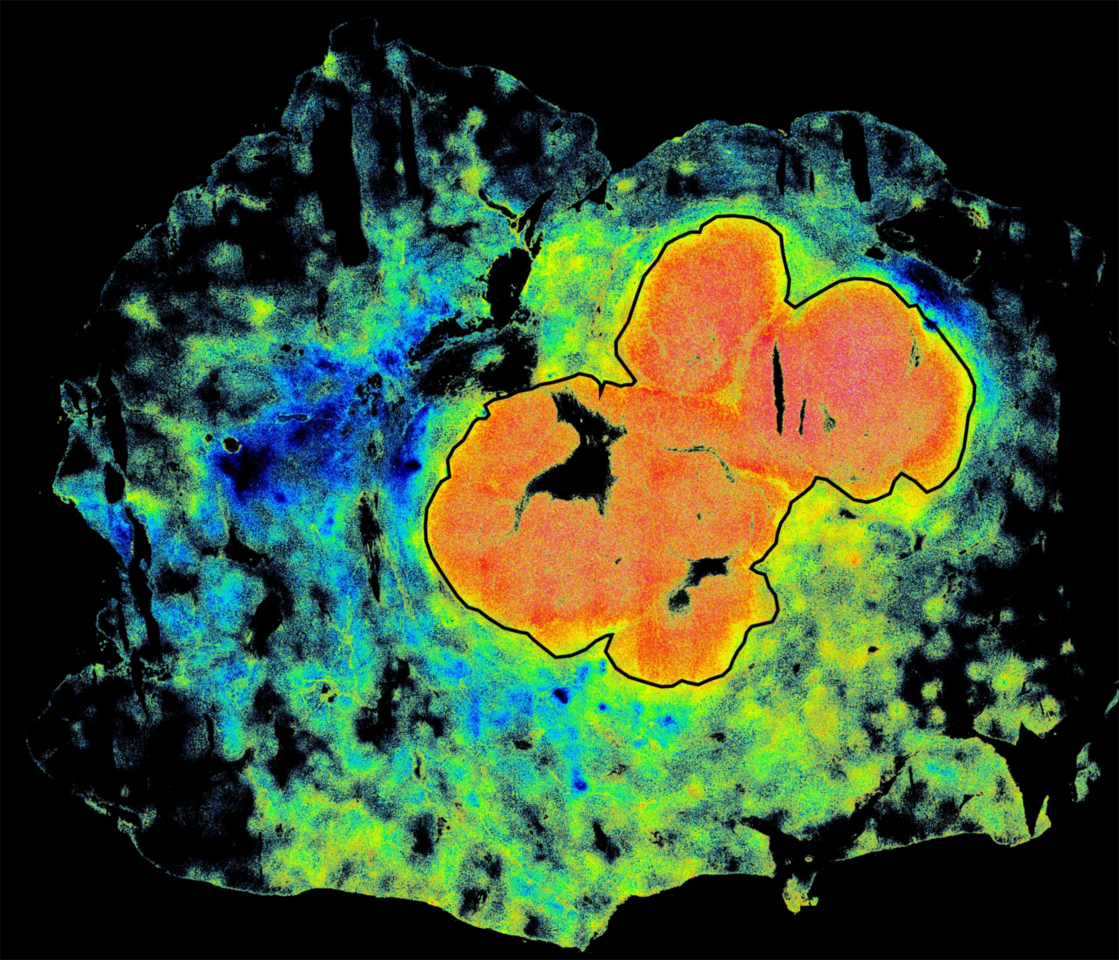

In the present work (Rahul Pal, et. al.,), we sought to establish clinically whether the phenomenon FLT enhancement of ICG in animal tumor models is also valid in humans. We initially recruited patients undergoing liver surgery at MGH and head and neck surgery at Mass Eye and Ear. We found that the FLT of ICG was indeed longer in tumors compared to normal liver or oral tissue, even when more ICG was apparently present outside the tumor. We additionally determined, using high-resolution microscopy, that the FLT enhancement occurred within small clusters of cancer cells, suggesting that the FLT enhancement of ICG could be a fundamental property in cancers. The enhanced lifetime allowed the separation of tumors from normal tissue with more than 95% sensitivity and specificity.

We subsequently initiated a collaboration across multiple institutions and evaluated specimens from more than 60 ICG-injected patients undergoing surgeries of multiple cancer types—liver, brain, tongue, skin, bone and soft tissue—at MGH, MEE, The University of Pennsylvania, University of Newcastle UK, and Leiden University NL. We observed consistently longer FLT in all the patients we studied and improved performance for tumor vs. normal tissue classification over standard fluorescence imaging. The FLT shift was consistent across tumor types in multiple patients and could also distinguish benign from metastatic lymph nodes. (Full text of our paper here:https://rdcu.be/doHy3)

The importance of this finding lies in the fact that FLT is an absolute property independent of the particulars of the camera or laser used and can be applied across multiple patients to identify a universal cancer threshold. Such a threshold needs to be established independently for microscopic imaging and widefield imaging of large areas. It is not yet clear how FLT imaging performs in patients treated with radiation or chemotherapy. Further, we do not yet know the dosage and timing of ICG injection for which the highest tumor vs. normal tissue separation occurs. This is likely to depend on the tumor type and location. Future studies will focus on the optimization of ICG injection timing and dosage and an optimal FLT threshold for each cancer type.

We also investigated the mechanisms of FLT enhancement in cancers in patients injected with ICG or other exogenous agents. It is well known that ICG is localized within the cancer cell lysosomes following internalization. The FLT shift within the lysosomes could be due to changes in the environment including polarity and viscosity, as well as binding to proteins such as albumin in the blood. Further investigation into the mechanisms is ongoing, and hopefully will lead to the design of new dyes that are brighter than ICG and can undergo a faster lifetime shift, so that patients can be injected at the time of surgery.

To translate FLT imaging to live intraoperative imaging in the clinic, it is necessary to develop cameras that can provide real-time imaging in the operating room. The imaging systems should be suitable for open surgery above the surgical bed, or for minimally invasive surgeries using laparoscopes. Ongoing work in our group is focused on developing and clinically validating lifetime imaging systems in these settings. Nevertheless, our work suggests that the combination of fluorescence lifetime imaging with ICG can be employed for improving surgical resections, thereby impacting patient lives.

(We acknowledge Gary Boas for the help in editing this article)

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Biomedical Engineering

This journal aspires to become the most prominent publishing venue in biomedical engineering by bringing together the most important advances in the discipline, enhancing their visibility, and providing overviews of the state of the art in each field.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in