Envy, Jealousy, and the Final Words of Mass Murderers

Published in Social Sciences, Ecology & Evolution, and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

What kind of story does a mass murderer want to leave behind? What image of themselves do they hope the world will remember?

Some leave sprawling manifestos full of hatred and ideology. Others leave behind nothing more than a brief suicide note, a few lines, an apology, an instruction to call their lawyer. These final writings, known as legacy tokens, can offer a direct glimpse into the emotional landscape of the offender just before their violent act. These texts are not merely explanations, they are parting performances, crafted to control the narrative, frame their identity, and influence how their violence is interpreted.

In our recent paper, we analysed a global sample of mass murderers using Latent Class Analysis, a statistical method that reveals groupings in large datasets. From this, we identified two distinct emotional profiles: one rooted in envy, and the other in jealousy.

Though often used interchangeably, envy and jealousy are not the same, and the difference matters. These emotions leave different narrative fingerprints, and they help us understand not just who offenders target, but how they frame their violence and why they write what they write. What they write may be horrifying — but it’s also revealing

Two Emotional Blueprints

Envy type offenders were generally younger. They had long histories of social rejection, often felt humiliated or excluded, and tended to target strangers in public spaces, malls, or their schools. Their legacy tokens were often lengthy, expressive, and grandiose. They described themselves as superior, misunderstood, and destined for greatness.

Pekka-Eric Auvinen, who shot eight people in a Finnish school, called himself a “natural selector” and described his act as evolutionary culling. His writings invoked Nietzsche, misanthropy, and cosmic destiny. He was, in his own mind, ''godlike'', above humanity, beyond morality. See figure 1.

Frank Vitovic best outlined the envious mindset when he wrote in his diaries:

''I see those people in the city and I admire them, and yet I hate them cos they've been the ones who've lumped shit on me all these years... they have all the things I want but will never have.''

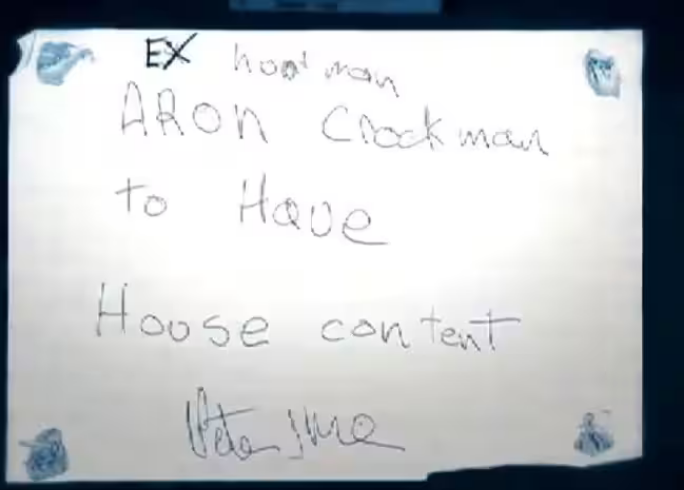

Jealous type offenders, by contrast, were generally older men. Their violence was usually domestic, involving a spouse or children, and was often preceded by relationship dissolution, or financial disaster. Instead of public spectacle, their tokens were brief and business-like: apologies to family, instructions about possessions. One older perpetrator wrote:

“Rented van at airport. I.D. in jacket pocket. I apologize to my family.”

Where the envious raged and demanded recognition, the jealous despaired and sought closure, and a final measure of control over a crumbling life.

Why the Difference?

Part of the difference may come down to age and life stage. Younger men — especially those who feel they’ve failed to earn status or respect — may turn to violence in an attempt to assert power. Their legacy tokens reflect a desire to be seen, to force the world to witness their pain and transformation into somebody. Research has shown that mass killers motivated by a desire for ''fame'' are younger on average than other types of perpetrators. The attention some receive after their crimes, including fan mail or online followers, only complicates the picture. Pictured below is the cell of James Holmes, who shot and killed 12 people at a movie theater, and later received numerous letters from followers.

Older men, on the other hand, often act after a personal collapse: a divorce, job loss, or financial ruin. Their writings reflect resignation rather than rebellion. In some cases, the goal is not recognition, but control — over their environment, their family, their memory.

The psychological depths of these offenders find a dark reflection in Shakespeare: Macbeth, driven by an all-consuming ambition and the fear of losing his 'destiny,' is entrenched in a cycle of jealousy and violence. He chooses a path 'stepped in blood.' In contrast, Richard III, fueled by the bitterness of his rejection as an unlovable man, carves his way to power through calculated cruelty. Richard's declaration that , ''since I cannot prove a lover... I am determined the prove a villain'', mirrors the envy, and narcissistic rage, which often drives younger mass murderers.

Why This Matters

Understanding what these offenders write, and why they write it, can offer real-world value. Legacy tokens help us identify emotional precursors to violence: feelings of humiliation, rejection, grievance, or rage. They also help us understand how offenders construct meaning and narrative around their acts.

These are often part of a deliberate performance, an attempt to frame the act, shape legacy, or even inspire others. The younger, envy-driven types often invoke past killers in their legacy tokens, and mirror the rhetoric, attire, and target choice of previous mass murderers. They want to be part of a story.

Final Thoughts

These findings are not meant to excuse or glamourise. But if we want to prevent mass violence, we must understand its emotional and psychological roots. Legacy tokens, though often distasteful, are one of the few direct sources we have.

They are the final words. And in those word, between the godlike delusions and the brief apologies, we find human emotions that, while twisted, are recognisable: the need to matter, the pain of rejection, the wish to be seen. If it is disturbing to recognize that their motives are of a continuum with normal motives (rather than belonging in a conveniently othered mental health realm), then this is an aspect of human nature that needs to be maturely faced.

Follow the Topic

-

Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology

The Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology covers the theory, practice and application of psychological principles in criminal justice, particularly law enforcement, courts, and corrections.

Ask the Editor – Collective decision-making

Got a question for the editor about Experimental Psychology and Social Psychology? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in