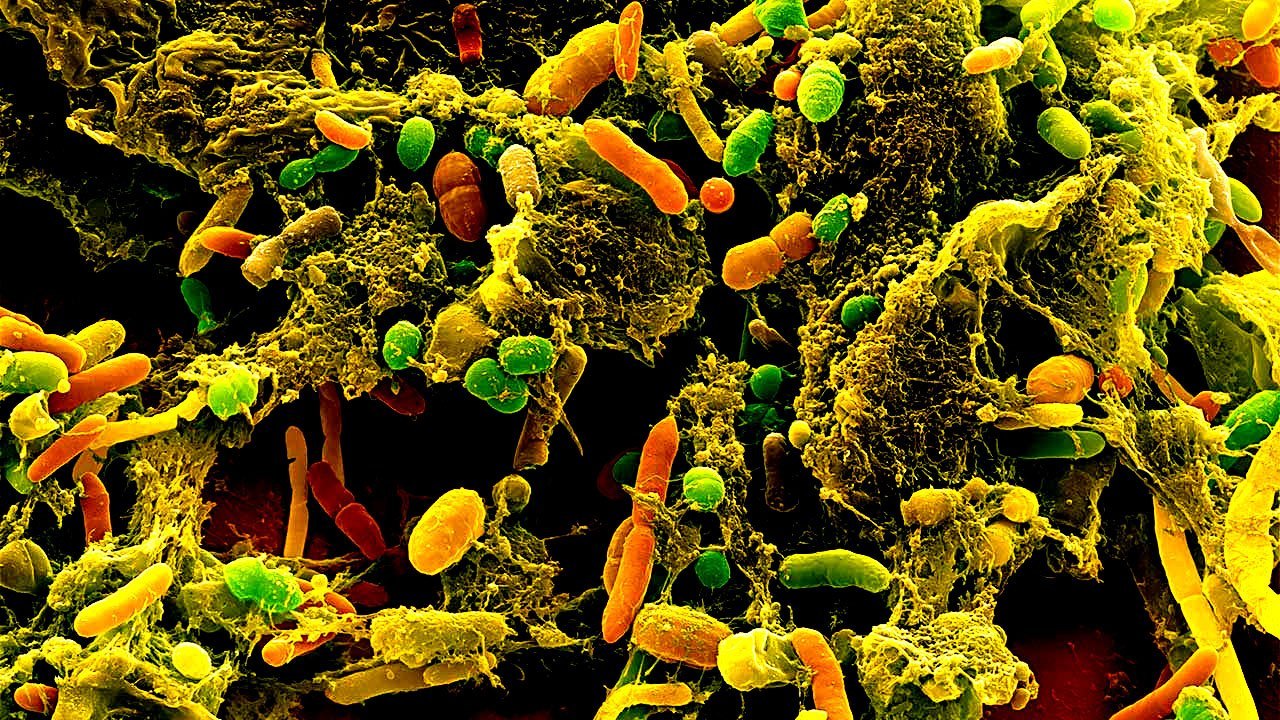

Many fundamental scientific questions remain unanswered about the processes that govern symbiotic relationships between microbiomes and their hosts. Take for example the poorly understood role of gut fungi. Fungi are omnipresent in microbial communities, and have well-described prominent roles in soil, marine, plant, and even food microbiomes. But what about the gut microbiome? Do gut fungi directly impact microbiome ecology, gut physiology and host immunity?

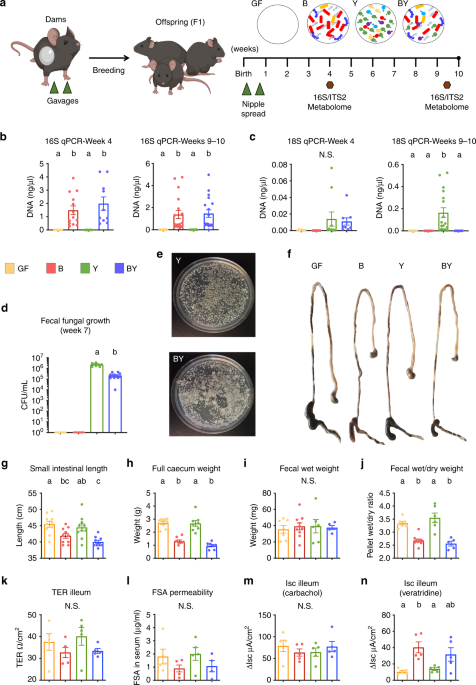

Answering these seemingly simple questions posed a major experimental hurdle: how can we tease apart the direct effects of fungi from those driven by bacteria if new fungal species change the bacterial microbiome composition? If we simply add fungi to bacterial communities, or treat a mixed community with antimicrobials, any observed host effects could be attributed to those caused by shifts in the bacterial community. To overcome this barrier, we opted for a defined approach using gnotobiotic mice colonized with consortia of mouse-derived bacteria, yeasts, or both. Colonizing mice exclusively with fungi had never been described before so we were unsure what would happen!

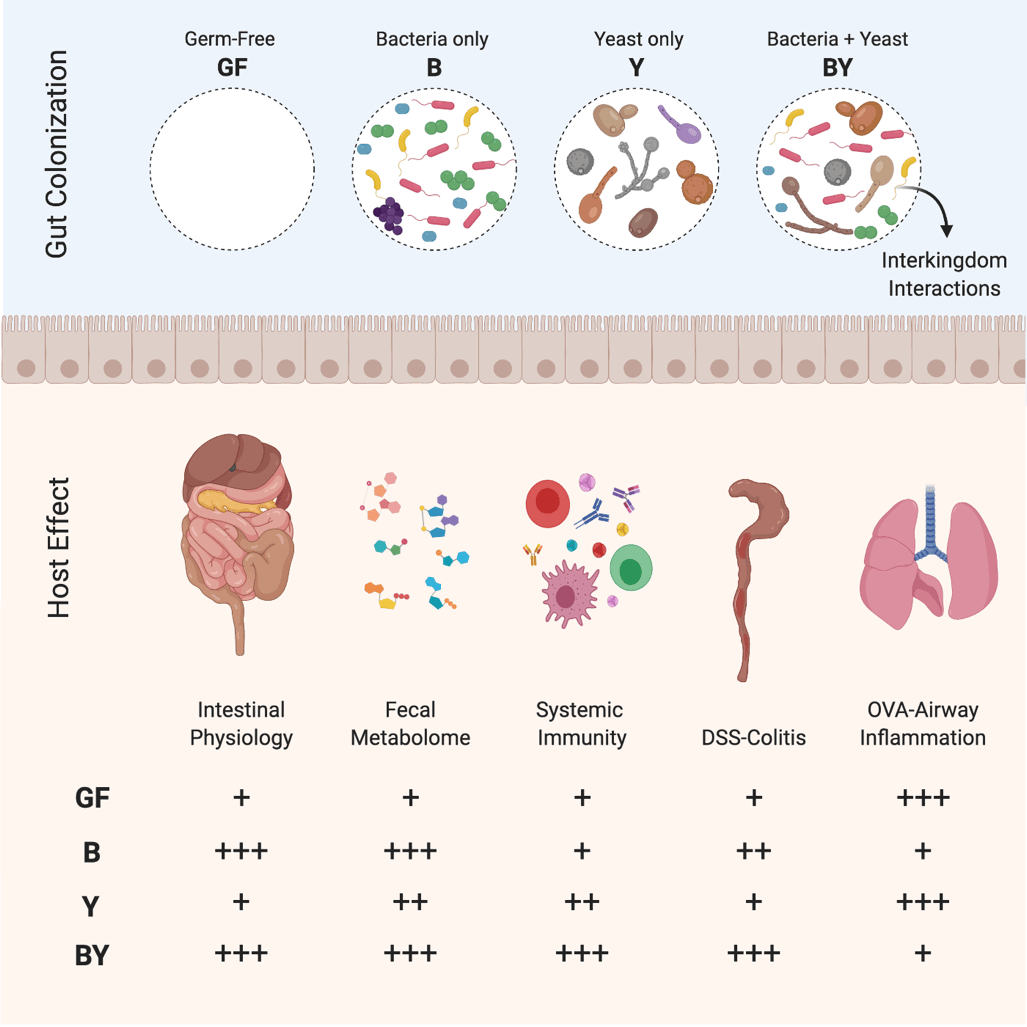

To our surprise, this artificial symbiotic construct worked well, and allowed us to conclude that fungal colonization induced changes in gut bacterial microbiome ecology while having an independent effect on innate and adaptive immunity in mice. We found conclusive evidence that yeasts are persistent gut dwellers, even in the absence of bacteria, although fungal diversity is favoured when bacteria are part of the community. Our ecological analysis revealed strong interkingdom antagonism and synergism between specific taxa, in line with what has been described in other microbial ecosystems. This broad array of interactions between fungi and bacteria shape this important ecosystem.

Remarkably, intestinal physiology and anatomy in mice exclusively colonized with fungi, including the most common human colonizer, Candida albicans, were essentially identical to germ-free mice. These findings suggesting that intestinal adaptations to microbial colonization are likely purposed to sustain bacterial colonization.

Our work also provided causal evidence that fungi are important in early-life immune education. Exclusive fungal colonization stimulated broad systemic immune responses in neonatal mice, yet these effects were enhanced in co-colonized animals, suggesting a synergistic effect when bacteria and fungi are present. While exclusive fungal colonization was insufficient to elicit overt dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis, bacterial and fungal co-colonization increased colonic inflammation. In contrast, exclusive fungal colonization increased ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation in mice, promoting infiltration of macrophages/monocytes in the airway. These findings showed that bacterial and fungal colonization contributes critical immunomodulatory signals that regulate the tone and phenotype of mucosal inflammatory responses to microbial and allergic antigens. The characterization of these signals has great potential for the prevention and treatment of diseases, like IBD and asthma.

Many questions remain unanswered. Our study used a limited consortium of fungi; we cannot rule out the possibility that other fungal species induce physiological response in the gut. Nor did our study interrogate the fungal-host driven mechanisms causing immune changes. We are currently exploring some of these questions and hoping others do too. Studying fungi, viruses, and other non-bacterial microbes will help us better understand the ecology and functionality of host-associated microbiomes.

This work was possible thanks to essential collaborations with other research groups with expertise in mouse gnotobiology (McCoy Lab), gut physiology (Sharkey and MacNaughton Labs), and lung physiology (Wilson and Kelly Labs). It has been a treat to work in the superb gnotobiology facility at the International Microbiome Center and recommend it to anyone considering gnotobiotic work with mice. This place is a gem!

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in