Honey-collecting in prehistoric West Africa from 3500 years ago

Published in Ecology & Evolution

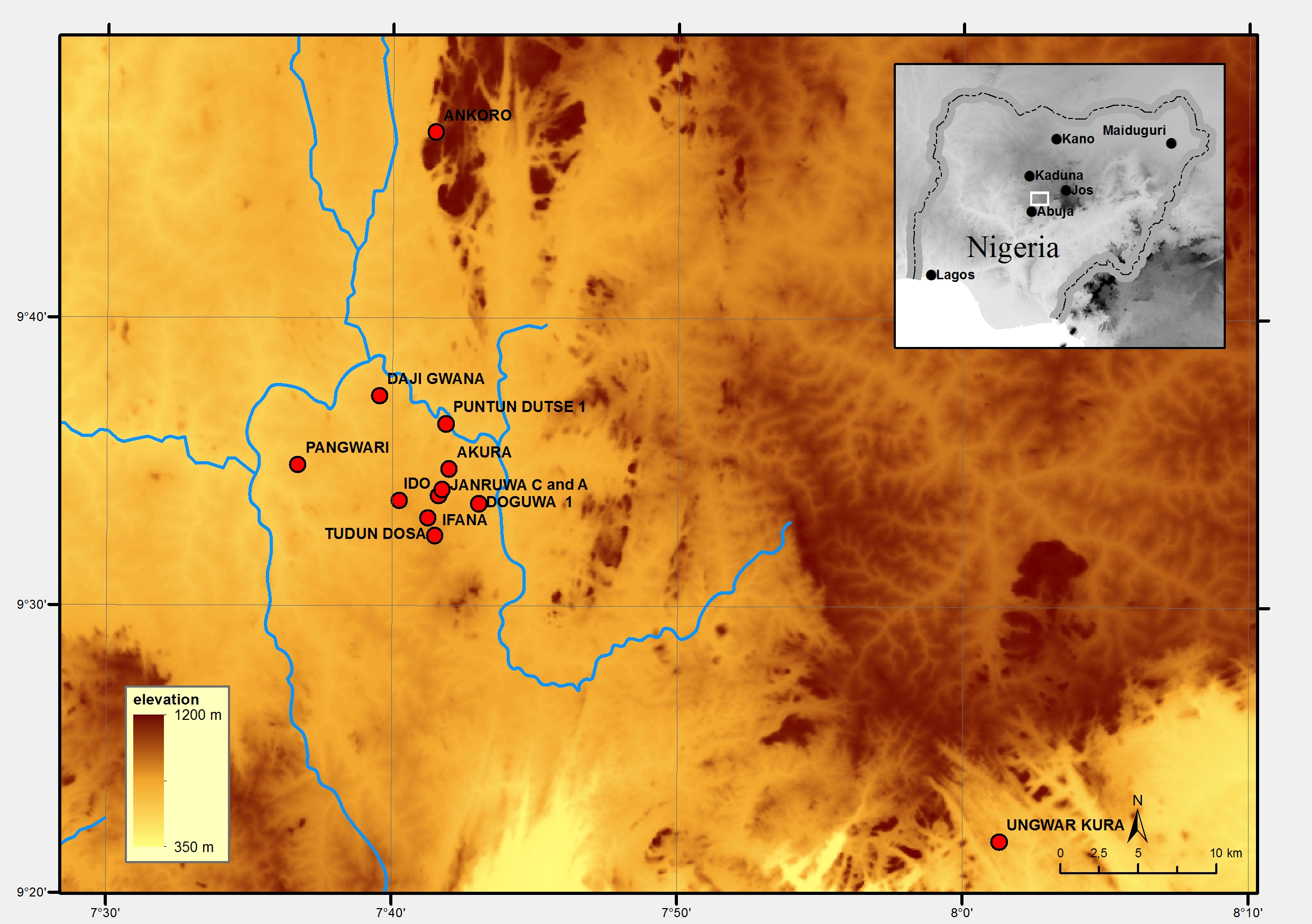

In this case, my collaborators, the archaeological team at Goethe University, Frankfurt, had been researching the enigmatic Nok culture (Figure 1) for several years. Known for their remarkable large-scale terracotta figurines (Figure 2) and early iron production, the Nok people lived around 3500 years ago in Nigeria, West Africa.

Figure 2. Nok terracotta figurines (Credit: Goethe University).

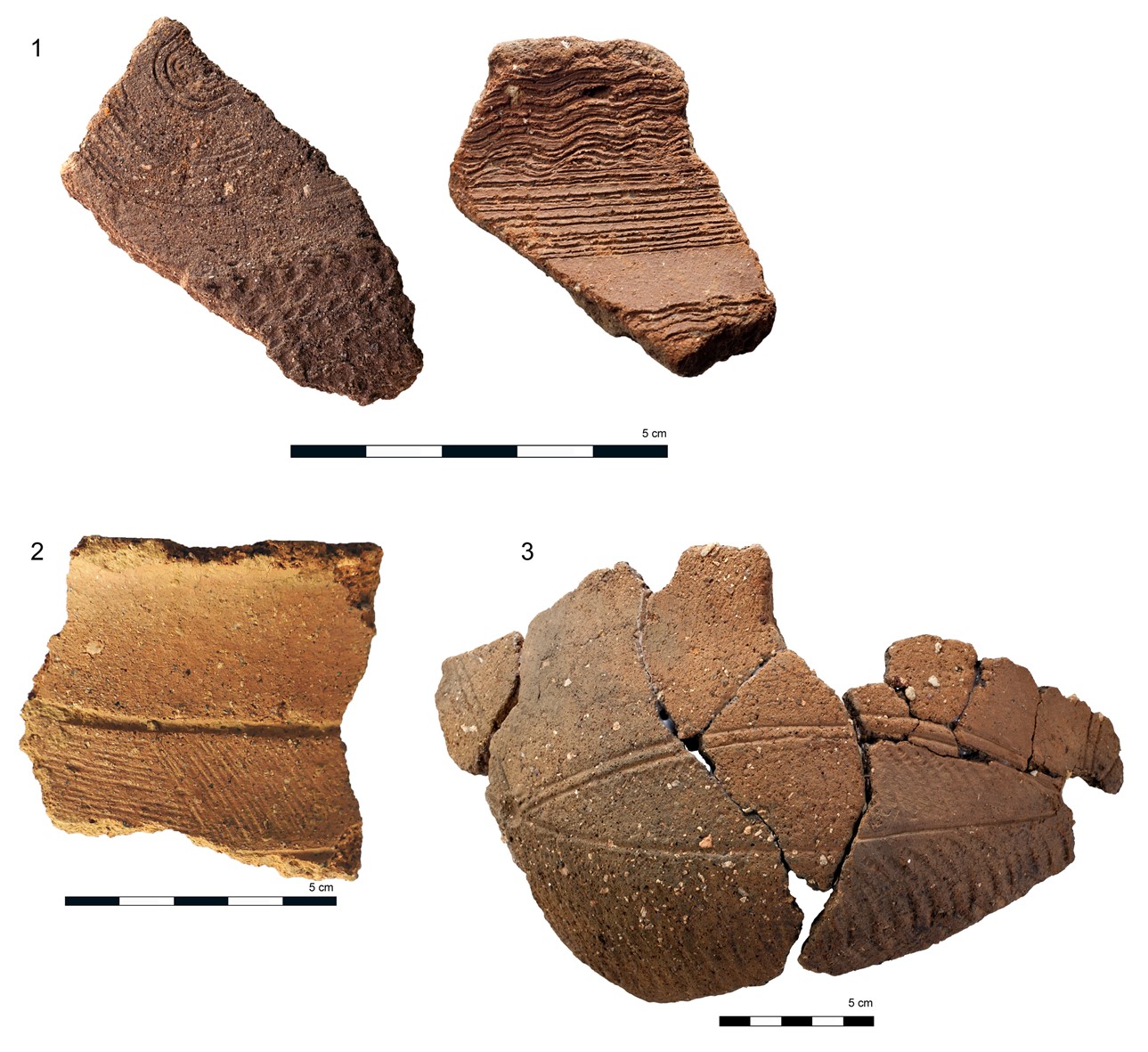

Several sites were excavated (Figures 3 and 4) but acidic soils meant there was little surviving organic material, such as animal bones or plant remains, which would tell us what Nok people ate and whether they grew crops and kept domesticates such as cattle or sheep or hunted wild game.

This meant that organic residue analysis was the only available means of investigating diet and subsistence among the Nok people. The technique involves grinding up small pieces of pottery (Figure 5) excavated from archaeological sites and chemically extracting lipids, the fats, oils and waxes of the natural world, providing a ‘biomolecular fingerprint’ of what foods were cooked in the pots. We expected to find evidence of animal fats, such as milk, or meat from ruminants (cattle, sheep and goat) and non-ruminant (pig) which are by far the most common foodstuffs identified in ancient pots.

Imagine our surprise then when our analyses revealed that overall one third of Nok vessels (over half in the Early Nok phase) contained a complex series of lipid biomarkers, comprising n-alkanes, n-alkanoic acids and fatty acyl wax esters, denoting the presence of beeswax. Determined genetically through the honeybee’s biochemistry, the composition of beeswax is extremely constant, offering a reliable ‘chemical fingerprint’ for detecting the presence of beeswax in archaeological vessels. Normally, whilst we might find evidence for beeswax in the odd vessel at an archaeological site, finding these high numbers of sherds in an assemblage has never happened before and told us something special was happening.

So, why was there beeswax in these ancient pots? Beeswax itself isn’t edible although it can be used for technological and medicinal purposes. Its presence in the pots is probably a consequence either of the processing (melting) of wax combs through gentle heating, leading to its absorption within the vessel walls, or, alternatively, beeswax is assumed to act as a proxy for the cooking or storage of honey itself.

%20(1).png) We can be sure ancient people would probably have sought out wild bee nests, much as our cousins the chimpanzees do, both for their honey, a rare source of sweetness, and possibly other bee products, such as the larvae, which are still eaten in many places across the globe today.

We can be sure ancient people would probably have sought out wild bee nests, much as our cousins the chimpanzees do, both for their honey, a rare source of sweetness, and possibly other bee products, such as the larvae, which are still eaten in many places across the globe today.

Honey offers a high-quality source of dietary energy, fat and protein and is often highly sought after by hunter-gatherers. There are several groups in Africa, such as the Efe foragers of the Ituri Forest, Eastern Zaire, who have historically relied on honey as their main source of food, collecting all parts of the hive, including honey, pollen and bee larvae, from tree hollows which can be up to 30 m from the ground, using smoke to distract the stinging and, often very aggressive, bees.

Honey may also have been used as a preservative to store other products. Among the Okiek people of Kenya, who rely on the trapping and hunting of a wide variety of game, smoked meat is preserved with honey, being kept for up to three years. This is a strong possibility for the few pots that did contain biomarkers suggesting the presence of both beeswax and meat products.

A further possibility is that the pots themselves may have been used as beehives (Figure 6), implying some management of the bees. This is commonplace in modern-day Nigerian traditional beekeeping, where pottery hives are either placed on the ground or in trees, while other types of hives made from clay, mud, straw or bark are always placed in trees. Little, or no, management of the hives takes place, in contrast to modern European beekeeping, mainly because of the tendency to abscond in tropical African honeybees. Once the colony has been in place for several months, harvesting of the combs takes place, sometimes destroying the nest. This usually takes place early in the rainy season, once the bees have exploited the freshly blossoming trees and before the heavy rains restrict the colony from collecting pollen.

Clay hives have been recorded in Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Malawi and Ethiopia and clay vessels with holes in them were used as beehives in Mozambique until the 1970s and are still used in Kenya and Uganda today. However, Nok vessels are generally only 20-30 cm diameter, and likely too small to have been used for these purposes.

Our identification of beeswax, and possibly honey, in Nok pots raises interesting questions on the antiquity of honey collecting in West Africa. Pottery was around at least 8000 years before this - were early hunter-gatherers in the region honey-hunting too? This question remains open for now ......

Finally, when a local forager visited the Ifana excavations in 2015, bringing with him freshly foraged honey to sell (Figure 7), no-one imagined that the pots they were digging up then would be found to contain the very same foodstuff, honey, likely exploited at that very spot by Nok people at least 3500 years ago.

To read more about our findings, please check out our paper, 'Honey-collecting in prehistoric West Africa from 3500 years ago', in Nature Communications. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-22425-4

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in