Growing up in New Zealand, I have always loved birds. I have fond childhood memories at my family home watching Tūī fight over sugar water on a home-made bird feeder, listening to them sing beautiful songs and being fascinated by their aggression.

However, I was never set on one group of organisms to study. It was during my time investigating evolution in parasites at the University of Otago with Robert Poulin and Fátima Jorge that I became interested in understanding speciation, the formation of new species, and how this is influenced by traits and environments.

When I moved to Melbourne in 2019 to start a PhD with Steven Chown, I sat down for one of our first meetings and discovered Steven was open to nearly any ideas, so I told him I wanted to study speciation. Steven suggested the honeyeaters, and that’s when my obsession began. Originating in Australia, honeyeaters are Australia’s largest bird clade containing just under 200 species. They currently range throughout Australia, Indonesia, the South Pacific, and New Zealand. The honeyeaters are a remarkable group of birds and include common Australian species such as the Noisy Miner, Scarlet Honeyeater, and Little Wattlebird, as well as my favourite New Zealand bird species, the Tūī.

Previously interested in how hosts might impact speciation in parasites, I shifted these ideas to broader patterns and wanted to look at how a species’ geographic range size might impact speciation in honeyeaters. When discussing these ideas in a meeting, Steven handed me a photocopy of a book chapter he authored with Kevin Gaston in 1999 titled Geographic range size and speciation, and I was hooked.

Since Darwin, a species’ geographic range size has commonly been hypothesised as a driver of speciation rates. This is based on the simple assumption that if speciation is to occur through the formation of geographic barriers, a larger range represents a greater area in which barriers may form. Despite the long history of these ideas, conflicting evidence for both positive and negative effects on speciation have been found, so I wanted to revisit the range size-speciation hypothesis with new techniques from both an ecological and evolutionary perspective.

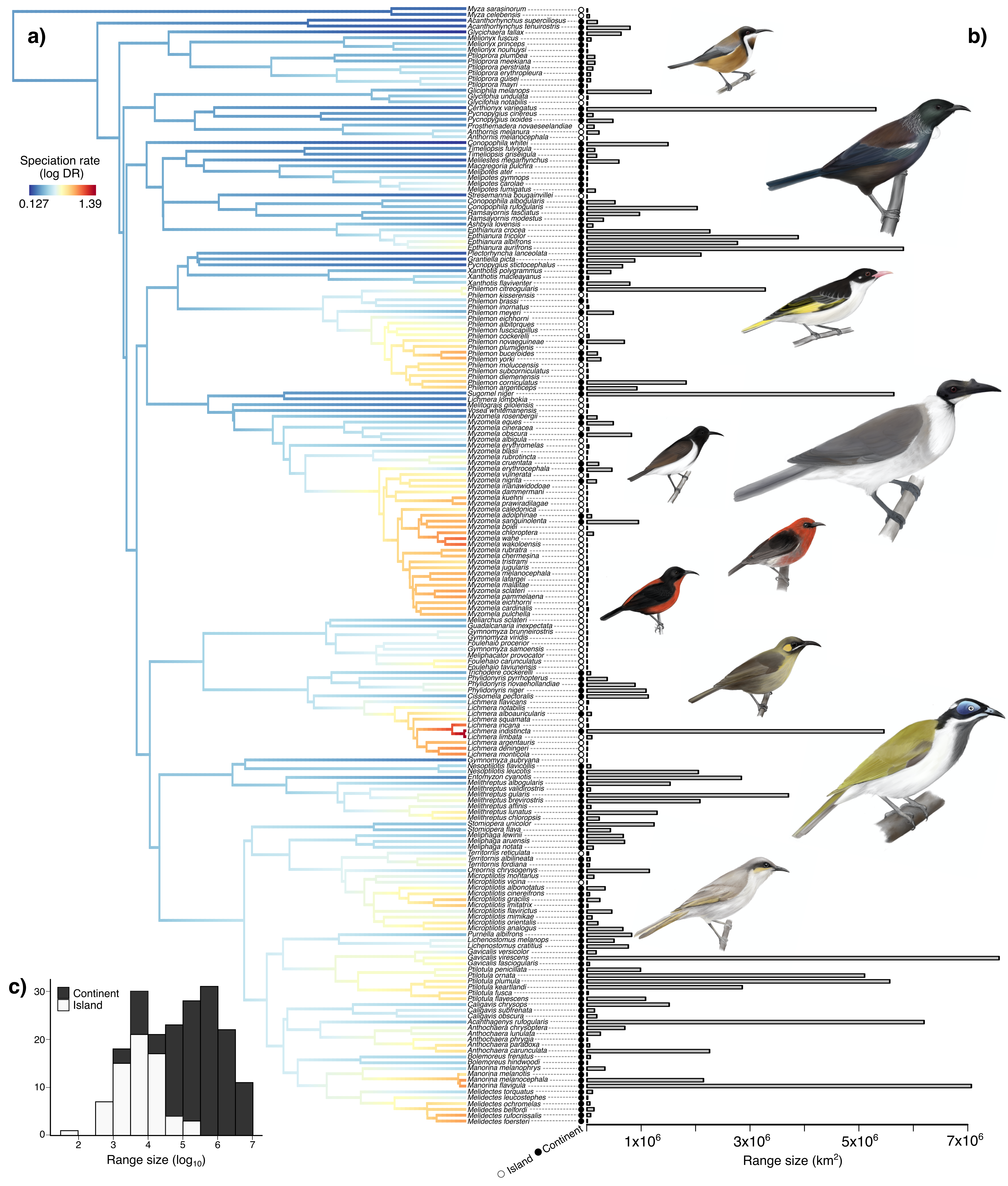

It turns out the geographic range size-speciation relationship is more complex than it might appear at first glance. A species range size itself is a complex trait, co-determined by other morphological traits. Body size is thought to influence the minimum geographic range size of a species, and how far a species is able to move (its dispersal ability) also sets a limit on its range. Furthermore, island and continental settings can constrain range sizes. A honeyeater restricted to a small offshore island, such as the Rotuma Myzomela, the honeyeater with the smallest range, is likely to have a smaller range than another species located on the continent of Australia, such as the Singing Honeyeater, which also happens to be the honeyeater with the largest range size.

After developing ideas and compiling data throughout 2019 and early 2020, with the help of my co-supervisor Matt McGee I was thrown into the world of phylogenetic comparative methods. All the initial analysis for this chapter was completed throughout 2020, which living in Melbourne meant experiencing never-ending lockdowns alongside my never-ending analyses. Despite the unprecedented times, focusing on my research helped, and I kept myself entertained by reigniting my passion for art through drawing honeyeaters, which have now become a big part of my research and PhD thesis.

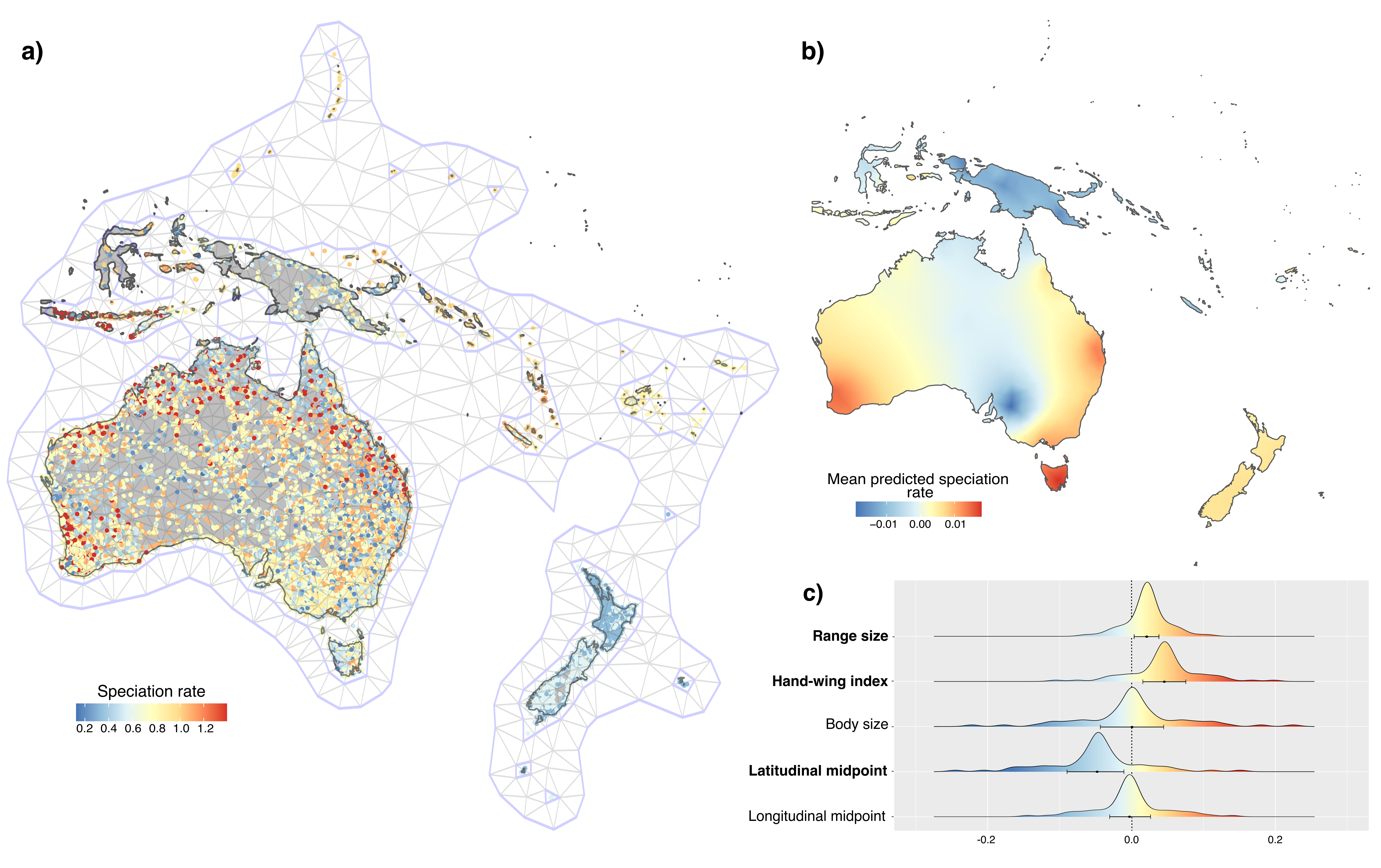

To consider the multiple interactions of traits and geographic setting on range size and speciation we used Bayesian phylogenetic structural equation models. At this stage it became clear that greater dispersal ability is important for speciation in honeyeaters, which was not surprising given that previous research has indicated dispersal events throughout Indonesia and the South Pacific played a prominent role in honeyeater evolution. We also found that islands had a significant effect on range size. Based on this we investigated the range size-speciation relationship in island and continental species separately, finding that in continental species larger ranges are associated with higher rates of speciation.

To then approach this question from an ecological point of view, we wanted to consider spatial distributions of species and traits and how this might impact the speciation-range size relationship. At this stage our analyses only considered phylogenetic covariance, the expectation that closely related species will be more similar to each other than they are to a randomly selected species, but we also wanted to account for covariance due to shared biogeographic occupancy. To achieve this, we used spatiophylogenetic analysis, which enabled us to consider both a spatial effect and a phylogenetic effect in a regression analysis. This model confirmed speciation rates are variable across both the continental and island settings, larger ranges are associated with higher rates of speciation, and that greater dispersal ability promotes speciation.

We then wanted to verify these results from an evolutionary perspective with the use of hidden-state dependent speciation and extinction analysis. Initially, I was expecting to confirm that larger ranges have higher rates of speciation and was confused when we uncovered almost the opposite, that small ranges and the combination of the smallest and largest ranges had the highest rates of speciation. The answer for this conundrum became apparent when considering the geographical context of the species. Many honeyeater species associated with smaller ranges are also restricted to islands, which was driving this pattern of smaller ranges having higher rates of speciation. Islands frequently play key roles in avian speciation, and we found evidence for this in honeyeaters. This impact of island speciation hotspots in honeyeaters is further evident in higher rates of speciation associated with species from the genera Philemon, Myzomela, and Lichmera, all of which include a greater proportion of island than continental species.

As Melbourne finally emerged from lockdown and my analyses came to an end, I now not only had a portfolio of honeyeater illustrations, but also some interesting results. Overall, we found that honeyeater speciation rate differs considerably between islands and the continents. Larger range sizes are indeed associated with higher speciation rates on continents, while dispersal ability influences speciation regardless of geographic setting. It turns out that honeyeaters proved Darwin’s original proposal for a positive relationship between range size and speciation likelihood to be right.

Follow the Topic

-

BMC Ecology and Evolution

An open access, peer-reviewed journal interested in all aspects of ecological and evolutionary biology.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Bioacoustics and soundscape ecology

BMC Ecology and Evolution welcomes submissions to its new Collection on Bioacoustics and soundscape ecology. By studying how animals use sound and how noise impacts them, you can learn a lot about the well-being of an ecosystem and the animals living there. In support of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 13: Climate action, 14: Life below water and 15: Life on land, the Collection will consider research on:

The use of sound for communication

The evolution of acoustic signals

The use of bioacoustics for taxonomy and systematics

The use of sound for biodiversity monitoring

The impacts of noise on animal development, behavior, sound production and reception

The effect of anthropogenic noise on the physiology, behavior and ecology of animals

Innovative technologies and methods to collect and analyze acoustic data to study animals and the health of ecosystems

Reviews and commentary articles are welcome following consultation with the Editor

(Jennifer.harman@springernature.com).

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 27, 2026

Ecology of soils

BMC Ecology and Evolution invites researchers to submit their work on soil ecosystems and their implications for environmental sustainability. Soils are living, dynamic systems that support a vast array of organisms, from tiny microbes to plants and animals. They play a vital role in keeping our planet healthy by recycling nutrients, storing carbon, and helping regulate water and climate. Understanding how soil life functions and adapts is essential for tackling major environmental challenges like climate change, habitat loss, and soil degradation.

This collection of articles aims to showcase the latest research in soil ecology, emphasizing the interactions among soil organisms, biogeochemical processes, and ecosystem functions across various landscapes. We invite submissions that explore the following topics:

•Microbial and faunal diversity in soils: Patterns, drivers, and functional roles of bacteria, fungi, protists, and invertebrates

•Soil biogeochemistry and ecosystem functioning: Nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, and soil health in both natural and managed ecosystems

•Soil-plant interactions: Rhizosphere processes, plant-microbe symbioses, and their effects on vegetation dynamics

•Land use and climate change impacts on soil communities: Responses of soil biodiversity and functions to agricultural intensification, urbanization, pollution, and climate shifts

•Soil metagenomics, phylogenetics, and functional ecology: Advances in molecular approaches for studying soil microbial and faunal communities

•Conservation and restoration of soil ecosystems: Strategies for maintaining soil biodiversity and ecosystem services in degraded landscapes

All manuscripts submitted to BMC Ecology and Evolution, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 15: Life on Land.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 02, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in