How a simple rule helped Seoul support local businesses—without fueling COVID-19

Published in Social Sciences and Earth & Environment

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, governments worldwide faced a dual imperative: protect livelihoods while containing a fast-spreading virus. Stimulus payments were a common tool to prop up spending, but they raised a concern—would encouraging people to shop and dine out inadvertently increase risky contacts and mobility?

In our Nature Cities article, “Geographic restrictions in stimulus spending mitigated COVID-19 transmission in Seoul,” we show how a simple design choice helped square that circle. South Korea’s 2020 program asked recipients to spend benefits within their city of residence, at brick-and-mortar establishments, and within roughly 16 weeks. In Seoul, this geography-first rule nudged people to spend locally, tempering the types of trips most associated with transmission. Our analysis suggests this policy kept infections lower than they otherwise would have been while still supporting the local economy.

What made Seoul’s policy distinctive

- Universal – and card-based. Households received up to US$815, regardless of income; funds were loaded onto credit/debit cards rather than distributed in cash.

- Targeted to local, offline sectors. Purchases were permitted at neighborhood shops and services (and generally not online or at large national chains).

- Time-limited and place-bound. Benefits expired in 16 weeks and had to be spent in the recipient’s registered city. People could travel freely and spend their own money elsewhere, but stimulus funds would not work out of town.

This was not a lockdown. Instead of suppressing mobility outright, the policy reshaped where spending occurred.

Our question was straightforward: did this geographically targeted design change where people spent, and did that spatial shift matter for transmission?

The Data we brought together

Seoul offers unusually rich data at the neighborhood (dong) level. We linked:

- Anonymized credit/debit card transactions that record each buyer’s home neighborhood and the location of the purchase.

- Mobile-phone mobility records tracking inter-neighborhood flows.

- Neighborhood-level COVID-19 case counts.

Our study window spans January 2019–August 2020 across 423 neighborhoods, covering 4+ million transactions and roughly 350,000 weekly inflows per neighborhood. This let us connect how stimulus shifted where people spent, how they moved, and what happened to infections—at a granular urban scale.

How we approached the analysis

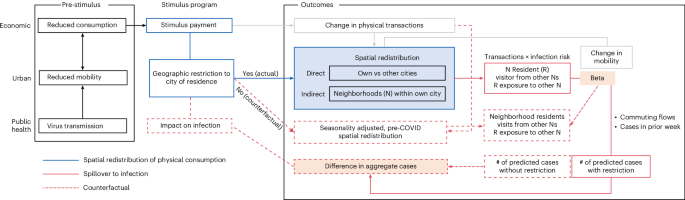

- Did the policy localize spending?

We compared the spatial distribution of transactions—within one’s own neighborhood, adjacent neighborhoods, other parts of Seoul, and outside Seoul—before and after disbursement, with 2019 as a reference. - Did that spatial shift matter for transmission?

We related within- vs cross-neighborhood spending to subsequent local infection rates, controlling for baseline commuting, prior infections, prevention measures, and public precautionary sentiment. - What if the geographic rule hadn’t existed?

We simulated a counterfactual where total spending stayed the same but was redistributed across space as in 2019, allowing us to isolate the public-health contribution of the location rule.

What we found

The stimulus worked economically—and it localized spending.

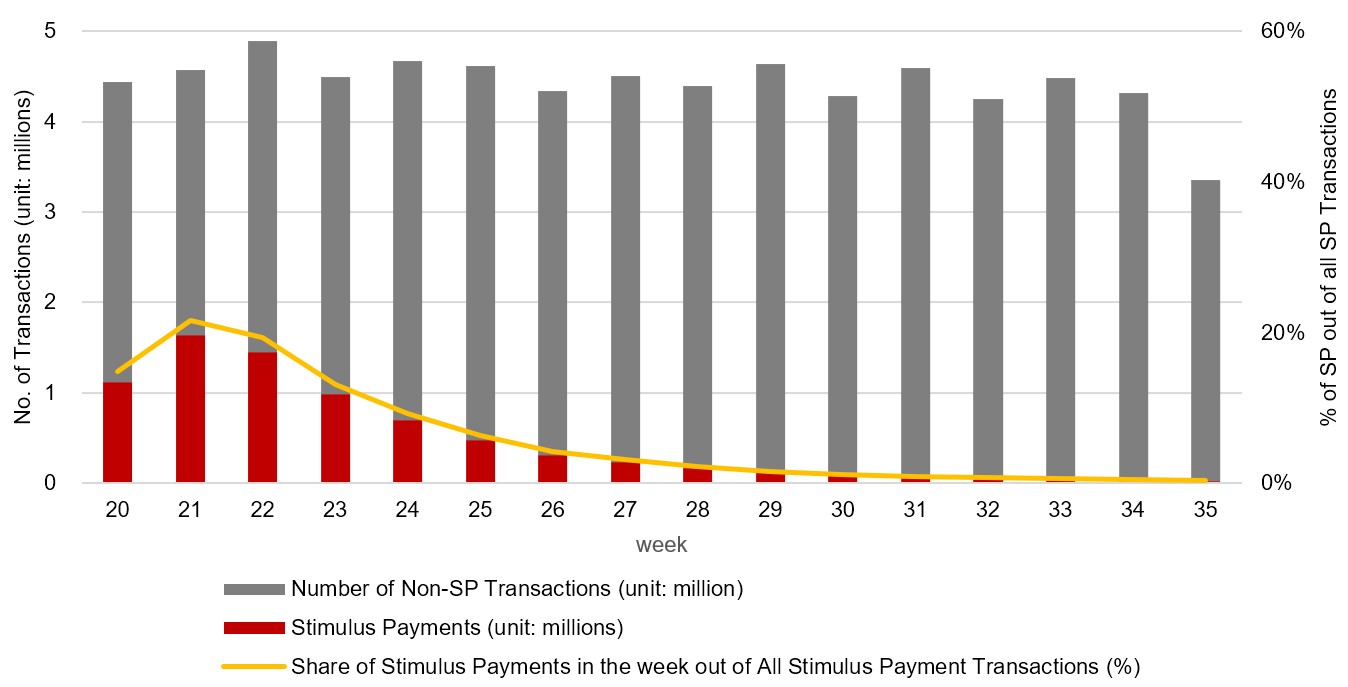

- Transaction volumes rose. After disbursement in 2020, average weekly transactions increased by 5%; stimulus-related purchases were 11% of all transactions in the window. Spending happened quickly—69% within four weeks and 92% within eight.

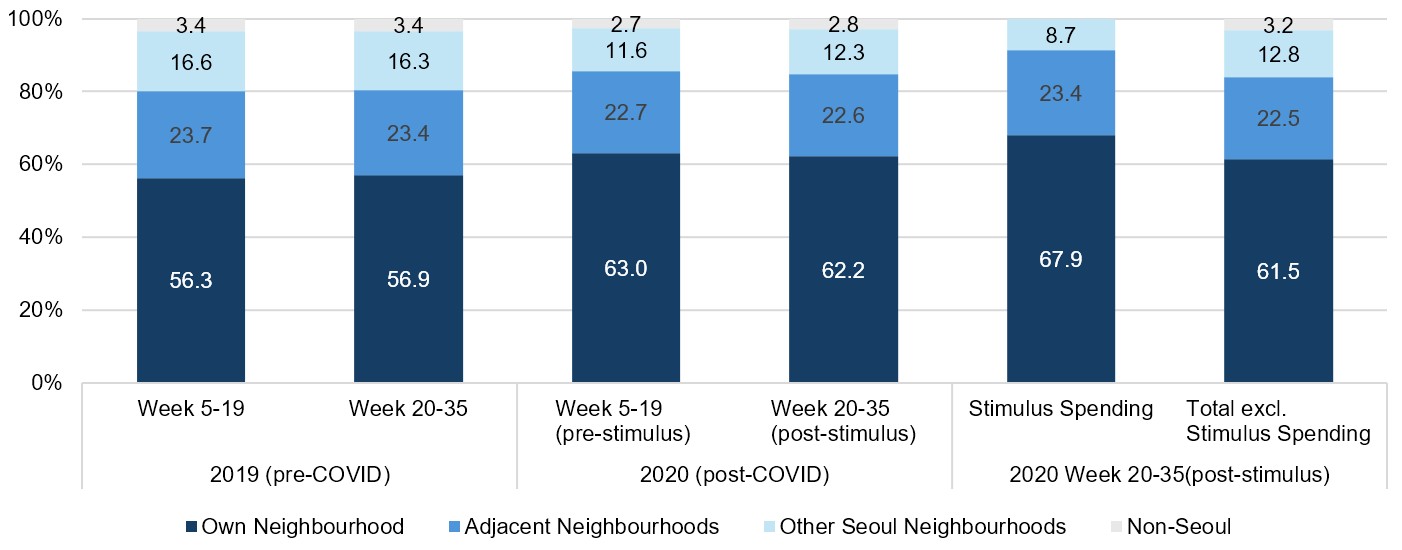

- Spending moved closer to home. The share of purchases within one’s own neighborhood rose to 62–63% in 2020 (vs 56–57% in 2019); outside-Seoul purchases fell to 2.7–2.8% (vs 3.4% in 2019). Stimulus-tagged purchases were even more local—about two-thirds in home neighborhoods and nearly a quarter in adjacent ones.

- Mobility increased only modestly. Relative to pre-stimulus 2020 (and adjusting for 2019 seasonality), cross-neighborhood mobility within Seoul was 2–8% higher, with only a brief uptick in cross-city trips. Given a sizable rise in transactions, this modest mobility response suggests people redirected spending to nearby outlets rather than traveling farther.

These patterns weren’t just artifacts of sector rules. Even excluding categories not eligible for stimulus (department stores, hypermarkets, gyms, hotels, entertainment), spending remained markedly more local. Public search interest in “geographic restrictions” outpaced “sector restrictions”, suggesting the location rule captured public attention and behavior.

Linking spending patterns to infections

We then asked whether localization mattered for transmission. In short: distance mattered.

- Stimulus-induced consumption was associated with measurable spillovers onto local infections, but within-neighborhood transactions were linked to smaller increases than cross-neighborhood spending.

- Short trips—often on foot and involving fewer unique contacts—appeared less risky than trips that crossed neighborhood boundaries.

These findings held when we accounted for prior infections, commuting patterns, prevention measures, and time-varying public precautionary sentiment. Stimulating proximate consumption appears less infection-prone than stimulating longer-distance, busier destinations.

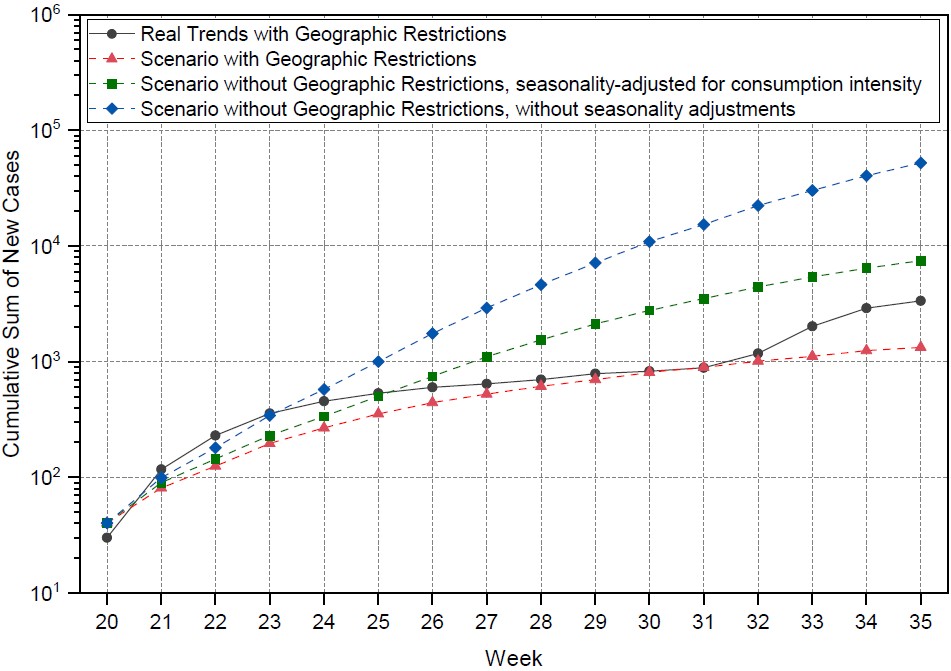

What might have happened without geographic restrictions?

Holding total transactions constant but redistributing them spatially as in 2019, infections would have risen faster without the restriction. During the first four weeks—when most spending occurred—we estimate at least a 17% reduction in cases relative to the unrestricted scenario, with thousands fewer cumulative cases over weeks 20–35 depending on seasonality assumptions. The localization effect carried a clear public-health benefit during the key spending window.

Why policy design details matter

Comparisons with other countries highlight the role of policy design:

- In the United States, one-off cash payments were often saved or used to pay down debt—good for household balance sheets but not targeted to local commerce.

- Japan’s Go To Travel program encouraged long-distance trips and was associated with higher infections.

- Seoul’s approach—time-limited, card-based, offline, and geographically constrained—channeled spending to nearby businesses while limiting higher-risk mobility.

A path forward for crisis-time stimulus

Our takeaway is practical: in an epidemic, where stimulus money can be spent matters. Cities considering crisis support could:

- Implement geographic and sector targeting to steer consumption to proximate, everyday amenities.

- Implement time limits that accelerate economic support when it is most needed, paired with clear communication.

- Monitor mobility and spending patterns to adjust design in real time.

Stimulus design is not one-size-fits-all. But Seoul’s experience shows how spatially savvy rules can reinforce the local economy while limiting higher-risk mobility.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Cities

This journal aims to deepen and integrate basic and applied understanding of the character and dynamics of cities, including their roles, impacts and influences — past, present and future.

Introducing: Social Science Matters

Social Science Matters is a campaign from the team at Palgrave Macmillan that aims to increase the visibility and impact of the social sciences

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in