How Hard is Waiting?

Published in Social Sciences

Writers and philosophers have long known that waiting is no one’s idea of a good time. Modern science agrees: this idea is central to the concept of opportunity cost, the marshmallow test, and a study where people preferred to give themselves electric shocks rather than sit alone with their thoughts. But research on mood has usually ignored this bit of common sense. It has assumed that only happy or sad events would change mood, and that the amount of time passing in between was irrelevant.

So how does our mood change as time passes? Until now, scientists had no real answer. This is surprising given how important mood is to our sense of well-being and to mood disorders like depression. Our team, led by Argyris Stringaris of University College London, Dylan Nielson of the NIH, and me, has data to offer.

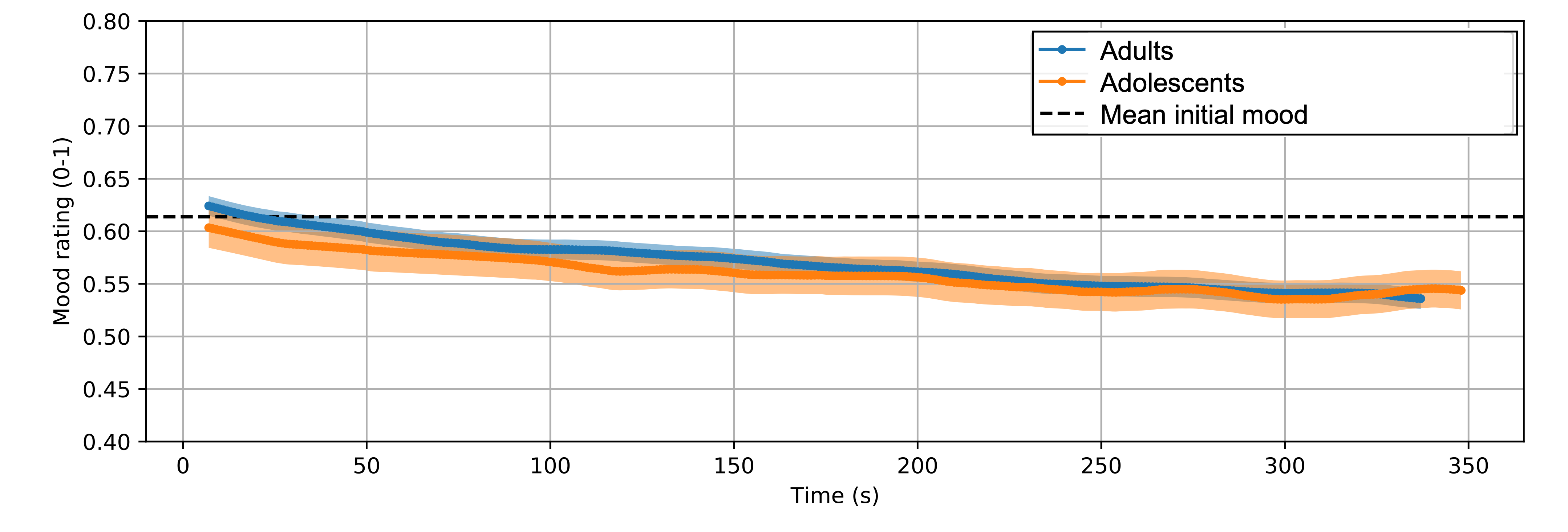

Our study asked more than 28,000 people to rate their mood periodically as they sat at rest or did common psychology study tasks online, including a large mobile app gambling game dataset from Robb Rutledge (currently at Yale). The results were clear: the average person’s mood declined about 2% per minute. We called this effect “Mood Drift Over Time,” or “mood drift” for short.

These results were not a fluke. We tried asking about mood less often. We tried a different mood rating method. We tried giving people different expectations about how long the wait would be. We tested teens as well as adults. We preregistered replications to avoid fooling ourselves. But through 20 different task variations and groups, the mood drift remained. People were being paid to do nothing, and they were still unhappy about it.

Not everyone felt this way. In fact, different people had very different mood drifts. These individual differences had some relationship to their level of boredom or the content of their thoughts as they waited, but these factors alone did not explain much. Still, a person’s level of mood drift was surprisingly stable over minutes, days, and even weeks. Some people were more bothered than others by our monotonous tasks.

Momentary mood ratings are subjective, but they are still standard in studies of mood and depression. In our study, people with depression had a mood that started lower and drifted down more slowly. But this effect on mood drift was very small.

A person’s sensitivity to reward had a greater effect. People whose mood responded more strongly to gains and losses in a gambling task also had larger downward mood drift over time.

For this reason, we think mood drift is related to the rate of happy events that you have come to expect in your daily life: when you’re waiting, you can’t go out and get those rewards, and that understandably bothers you. This would explain why people who are more sensitive to rewards in our tasks are also more upset when they can’t get them.

This idea could link mood drift to our constant “explore/exploit” decisions. Downward mood drift may help us decide to explore (i.e., try something new) rather than exploit (i.e., stay on task). People with depression often value rewards less, and their reduced mood drift could contribute to their reduced motivation to explore. But we need further research to be sure about this.

For now, we should recognize that waiting times in psychology and neuroscience experiments have unintended consequences. And there is a lot of waiting. Participants wait for setup and anatomical brain scans. “Resting state” scans, where participants simply stare at a plus sign, are in vogue.

If one group of participants is forced to wait longer than another before a task, they’ll start that task in a worse mood. This could lead to changes in brain activity and behavior that the researchers might mistake for a difference in that group’s traits. We suggest that researchers start standardizing, accounting for, or at least reporting these waiting periods.

As a rule, research tasks are neutral and unexciting, which supposedly keeps researchers in control. Our study suggests that these researchers have been punishing their participants without realizing it. This supports the position of some researchers that naturalistic tasks (a central theme of my lab) can tell us more about real-life brain activity than rest or finely controlled experiments can.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Human Behaviour

Drawing from a broad spectrum of social, biological, health, and physical science disciplines, this journal publishes research of outstanding significance into any aspect of individual or collective human behaviour.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in