How we Mapped the Unwritten Rules of Human Behavior Across 90 Societies

Published in Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

Why is it that some behaviors feel universally inappropriate while others seem to depend entirely on where you are? We all navigate these unwritten codes constantly—knowing instinctively not to laugh loudly at a funeral or answer our phone during a job interview. But how universal are these intuitions? And are they changing as our world becomes more connected?

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

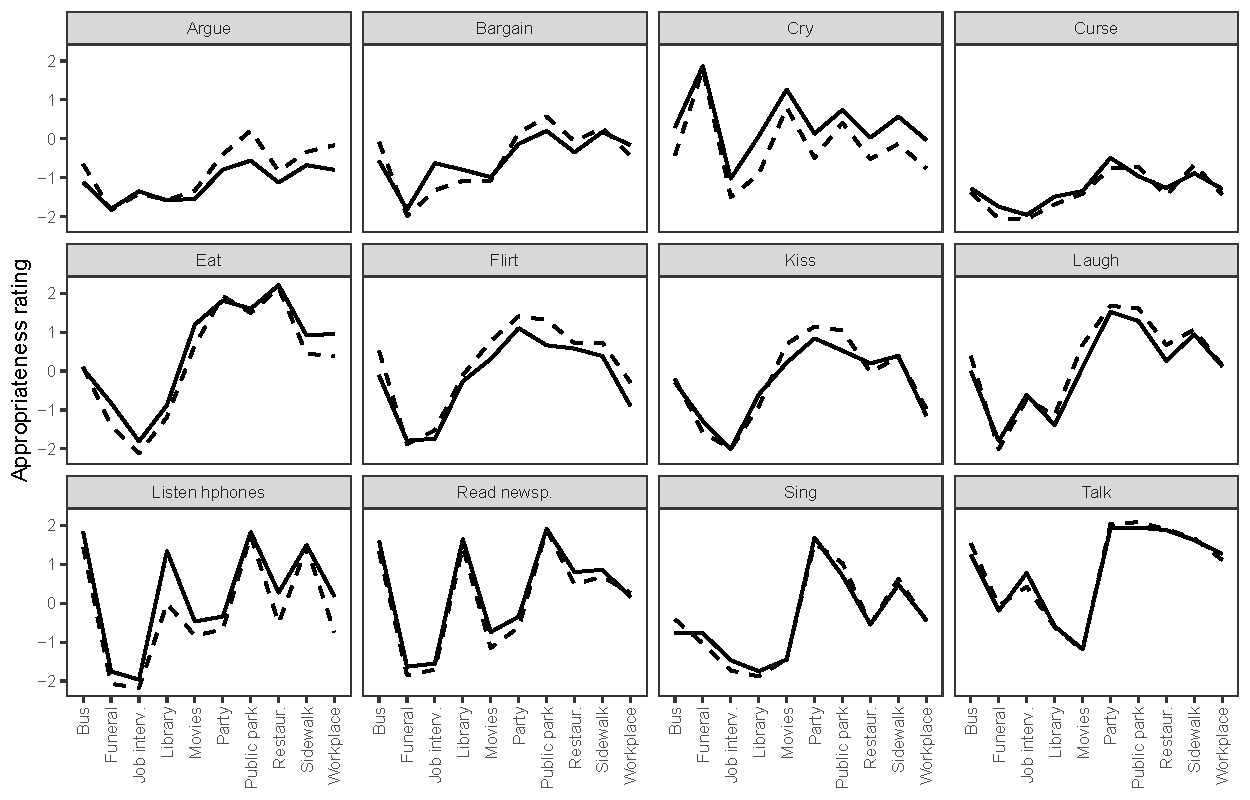

Our journey began with a remarkable study published in 2011 by Michele Gelfand and her colleagues, which among other things measured how appropriate 180 different behavior-situation combinations were across 33 societies—things like "arguing at a party" or "crying in the library." It was groundbreaking work aimed at understanding which cultures are tighter and which are looser. However, it did not seek to understand why norms vary in different ways for different behaviors.

Twenty years had passed since the data in Gelfand’s study was collected. The world had changed dramatically. Social media has transformed how we communicate. Globalization has accelerated. What would those same measurements look like today? And what if we could expand the study to truly represent the entire globe? And, most excitingly, not just map the patterns but explain them?

Rather than starting from scratch, we built directly on Gelfand's foundation, using the same behaviors and situations. This approach—many behaviors, many situations, many societies—creates a perfect laboratory for testing theories about how social norms work.

Building a Global Network

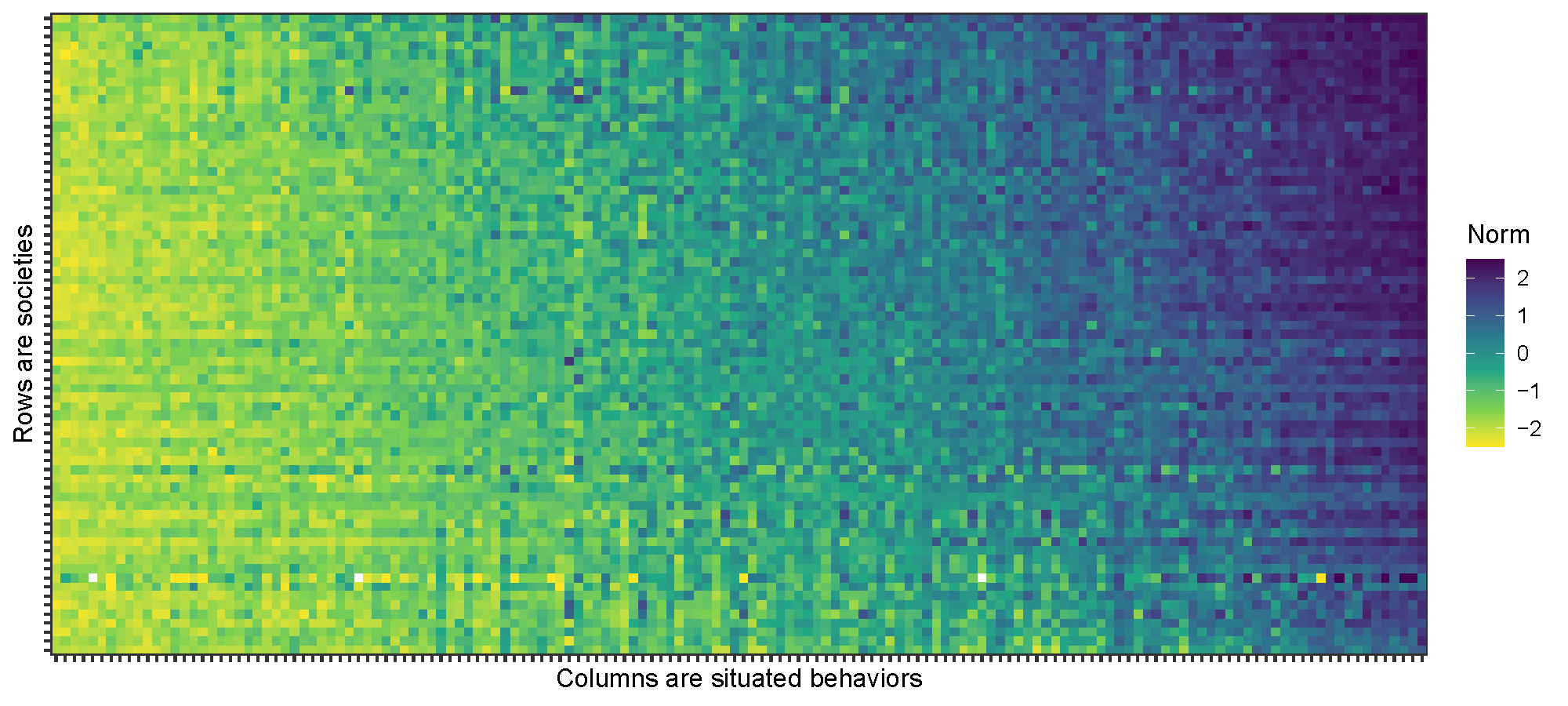

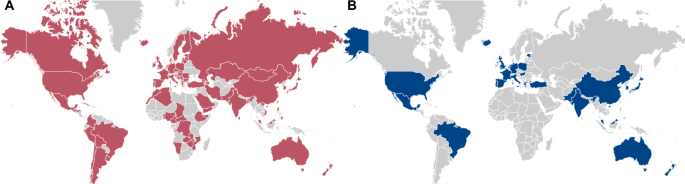

The ambitious scope we envisioned required a truly international collaboration. Through the Global Social Norms research network, we connected with nearly 150 researchers across six continents who shared our passion for understanding human social behavior. The logistics were staggering. The data collection needed to be coordinated across different languages, cultures, legal systems, and research infrastructures. Some colleagues had to navigate ethics committees that had never seen a study quite like this. Others had to adapt the survey for societies where certain behaviors (like public displays of affection) required special cultural sensitivity. What emerged was probably the largest study of everyday social norms ever conducted—25,000 participants across 90 societies, from Sweden to Somalia, from Canada to Central African Republic. Each dot on our global map represented not just data points, but real people sharing their intuitions about social appropriateness.

A Global Grammar of Everyday Norms

When we first analyzed our data, we experienced genuine surprise. The first revelation came when we compared our results with Gelfand's 20-year-old data. Despite decades of social transformation, everyday norms were remarkably stable. People still found the same behaviors inappropriate in the same situations. Moreover, the small shifts we observed were very systematic across countries and mostly in the direction of norms becoming more permissive overall.

The second surprise was even more striking. Despite studying 90 vastly different societies—from wealthy Nordic countries to developing nations in sub-Saharan Africa—we found extraordinary agreement about what's appropriate where. A behavior deemed inappropriate in rural Bangladesh was typically also seen as inappropriate in urban Australia. The variation between different behaviors in the same society was much larger than the variation for the same behavior across different societies. This was unexpected because discourse on social norms often focus on cultural differences rather than cultural similarity.

Connecting the Dots

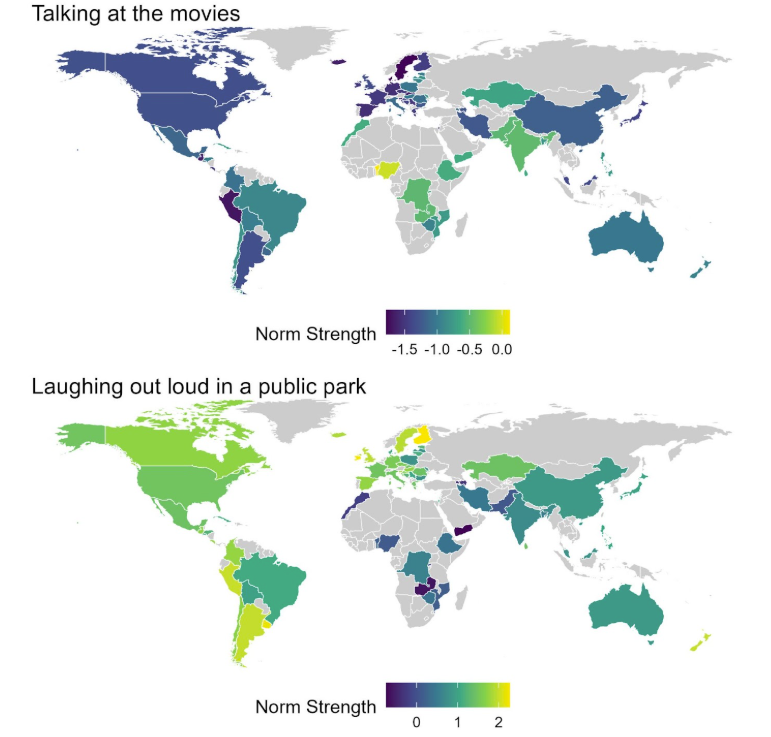

But similarity doesn't mean uniformity. The subtle differences we did find across societies followed intriguing patterns that led us to our central theoretical questions: What makes some behaviors universally inappropriate? Why are certain behaviors more acceptable in some societies than others? And what characterizes those societies?

To answer these questions, we added new measures to the original study design. We asked people not just whether behaviors were appropriate, but why someone might disapprove. We also measured what kinds of moral concerns were most important to people in different societies. The analysis revealed an elegant underlying structure. Three main concerns drive social judgments everywhere: whether a behavior is vulgar (coarse or indecent), inconsiderate (harmful to others), or lacking sense (pointless or self-defeating). But societies weigh these concerns differently based on their cultural values.

These differences in weights mean that a culture’s relative tightness-looseness for a specific behavior is relative to the type of moral concern it evokes. Societies that prioritize individual freedom and rights tend to be more tolerant overall, especially of behaviors others might find vulgar, but at the same time they're stricter about behaviors that harm others.

The Human Story Behind the Data

Underneath these scientific findings are thousands of human stories. Every data point represented someone's lived experience of social appropriateness—their intuitions about respect, consideration, and community belonging developed through a lifetime of social interaction. Together, these individual responses painted a clear picture of the freedoms and boundaries of the social world. The remarkable consistency we found suggests something profound about human nature. Despite our surface-level differences, we seem to share fundamental intuitions about social behavior. Everywhere we look, we see people caring about not harming others, about maintaining dignity in formal situations, and about behaviors making sense in their context. And across cultures, we mostly agree on which behaviors let us reach these goals.

Yet the subtle variations we observed remind us that culture still matters. The same underlying concerns get expressed differently depending on what a society values most—individual freedom or collective harmony, innovation or tradition, care for others or respect for authority. At the same time, we found that norms are changing in consistent ways in different cultures, suggesting a shared trajectory of cultural evolution.

Our findings offer some hope for our polarized world. While we often focus on what divides us, this study reveals the deep commonalities in how humans navigate social life. Understanding these shared foundations might help us bridge cultural differences with greater empathy and effectiveness. The unwritten rules that guide our daily interactions aren't random or arbitrary—they reflect universal human concerns about cooperation, respect, and community. That's a finding to celebrate, and it was worth the efforts of 150 researchers and 25,000 participants across 90 societies.

(The poster image was generated by Gemini.)

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Psychology

An open-access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary. The scope of the journal includes all of the psychological sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Intensive Longitudinal Designs in Psychology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Replication and generalization

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Dec 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in