Impact of residential solid fuel usage and fuel conversion on children’s lung function

Published in Earth & Environment and Public Health

According to the statistics of GBD, household solid air pollutants are related to 197.05 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs; 95%CI: 121.14, 321.17) per 100000 people for chronic respiratory diseases1. In China, the mortality risk caused by solid fuel combustion is generally high2. Given the rapid socioeconomic development, China has implemented several household energy intervention programs over the past few decades3,4. With the adjustment of energy sources policy, general public could convert energy type under health or economic concerns. However, further analysis is essential to understand the relative health effects.

As the susceptible population of air pollution, children's lung function is more likely to be adversely affected by the use of residential solid fuel5,6. In general, schoolchildren population is in a critical period of growth and development of respiratory system, and their lung function is relatively vulnerable to air pollution. Since solid fuel usage remains a health issue for some developing countries, nationwide longitudinal studies of lung function in children are important.

We conducted a perspective cohort study among 46 cities, from 28 provinces, municipalities, or municipal districts across all 7 geographical divisions in China. A total of 78 counties were recruited in our study, and 9997 participants from grade 3 to grade 6 and 24371 visits were included in the analysis.

All the participants were asked to provide detailed information about the conditions of household fuel usage. Clean fuel usage for both cooking and heating would consider to be clean fuel using participants, otherwise the participants would be assigned as solid fuel exposure. We also assessed the change of residential solid fuel type. The changing of fuel types was defined by the fuel type using during the last visit compared to the first visit, and was divided into the following types, always clean, solid to clean, always solid and clean to solid.

Pulmonary function tests included forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), peak expiratory flow (PEF), and forced expiratory flow (FEF) at 25% and 75% (FEF25, FEF75). The pulmonary function test was conducted by the medical staff in charge of pulmonary function test in the hospital or physical examination center.

Study findings

Overall, we found that pulmonary lung function decreased among children exposed to household solid fuel, and children who persistently used solid fuel would suffer more significant lung injuries. Participants with allergies history are more susceptible to residential solid fuel exposure.

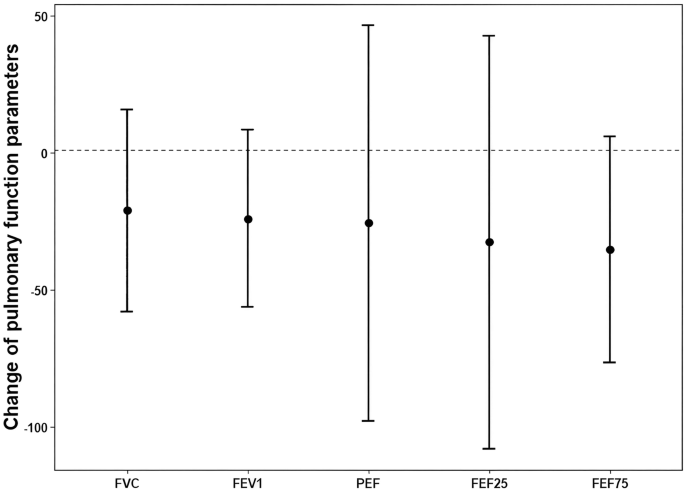

Our study found that exposed under residential solid fuel would affect lung function of schoolchildren. Among the participants who used solid fuel in the residence, FVC marginal decreased by 21.2 mL (95%CI: -15.7, 58.1). The usage of residential solid fuel was also associated with drop of 24.1 mL (95%CI: -8.4, 56.6) in FEV1, and 35.4 mL/s (95%CI: -5.9, 76.7) in FEF75. PEF (-25.7 mL/s, 95%CI: -98.0, 46.5) and FEF25 (-32.7 mL/s, 95%CI: -108.2, 42.7) also decreased with residential solid fuel usage.

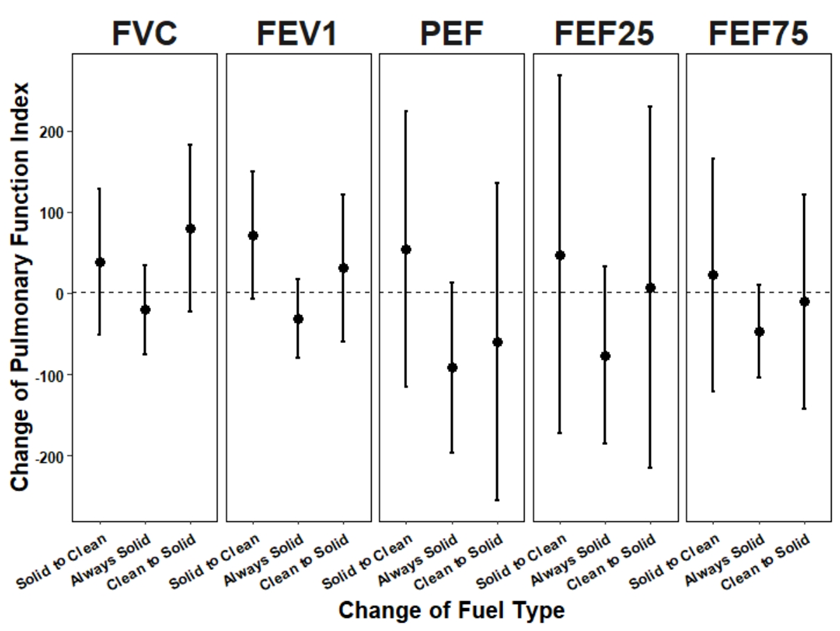

Compared with persistent clean fuel users, fuel conversion has adverse effect on lung function. Children who persistently used solid fuel suffered more lung injuries compared to persistent clean fuel users. Compared to the participants who are persistent users of clean fuel in the residence, the participants who are persistent solid fuel users demonstrated decline in PEF by 92.0 mL/s (95%CI: -12.8, 196.8), and they also experienced decrease of 46.6 mL/s (95%CI: -10.2, 103.5) in FEF75. Participants who switched their fuel type from solid fuel to clean fuel showed no significant association compared to those who are persistent clean fuel users.

Effect of changing residential fuel type on lung function.

Our study also found that the lung function of children with allergic history is more likely to be affected by the usage of solid fuel. Participants with allergy history showed significant decrease of 241.6 mL/s (95%CI: 44.3, 438.9) in PEF and 117.4 mL/s (95%CI: 7.1, 227.7) in FEF75, indicating greater effects felt by those without reported allergy history. Among the users of residential solid fuel, male participants experienced significant drop of 52.2 mL (95%CI: 1.2, 103.3) and 59.1mL/s (95%CI: 4.5, 113.8) in FVC and FEF75, respectively; while female participants exhibited little change of lung function. Participants with respiratory symptoms showed significant drop of 102.4 mL/s (95%CI: 1.0, 203.9) in FEF75, while those without respiratory symptoms had no obvious change of lung function. There was little difference between participants with different BMI, mother education, with or without residential passive smoking or pet keeping. No significant difference between north and south region of China was found in the study.

Conclusion

This study quantitatively evaluates the health effects of solid fuels on children, provides a reference for further precise prevention and control of solid fuel pollution, and provides guidance for public protection measures. Governments should develop clean fuels and encourage households to reduce their use of solid fuels and transition to clean fuels. Hospitals should pay attention to children's health and give parents protection guidance. Schools should strengthen children's health education, give protective guidance, and always pay attention to children's health. Parents should use clean fuels as much as possible in their homes and reduce the use of solid fuels. Children should improve their awareness of the health effects of solid fuels, strengthen personal protection, use clean fuels, and seek medical attention in time if they have adverse symptoms.

This national wide multi-center perspective study revealed the health impact of domestic solid fuel usage on lung function among school children population, and revealed the population susceptible to solid fuel exposure. The study findings emphasized the importance of using and maintaining using clean energy for indoor cooking and heating, which can positively contribute to public health.

References

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Results. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2022. Available from https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

- Lin HH, Murray M, Cohen T, Colijn C, Ezzati M. 2008. Effects of smoking and solid-fuel use on copd, lung cancer, and tuberculosis in china: A time-based, multiple risk factor, modelling study. Lancet 372:1473-1483.

- Jiang X, Sommer SG, Christensen KV. 2011. A review of the biogas industry in china. Energy Policy 39:6073-6081.

- Tao S, Ru MY, Du W, Zhu X, Zhong QR, Li BG, et al. 2018. Quantifying the rural residential energy transition in china from 1992 to 2012 through a representative national survey. Nature Energy 3:567-573.

- Dherani M, Pope D, Mascarenhas M, Smith KR, Weber M, Bruce N. 2008. Indoor air pollution from unprocessed solid fuel use and pneumonia risk in children aged under five years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ 86:390-398C.

- Po JY, FitzGerald JM, Carlsten C. 2011. Respiratory disease associated with solid biomass fuel exposure in rural women and children: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 66:232-239.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in