Imposter syndrome: an inevitable consequence of filling so many different niches?

Published in Ecology & Evolution

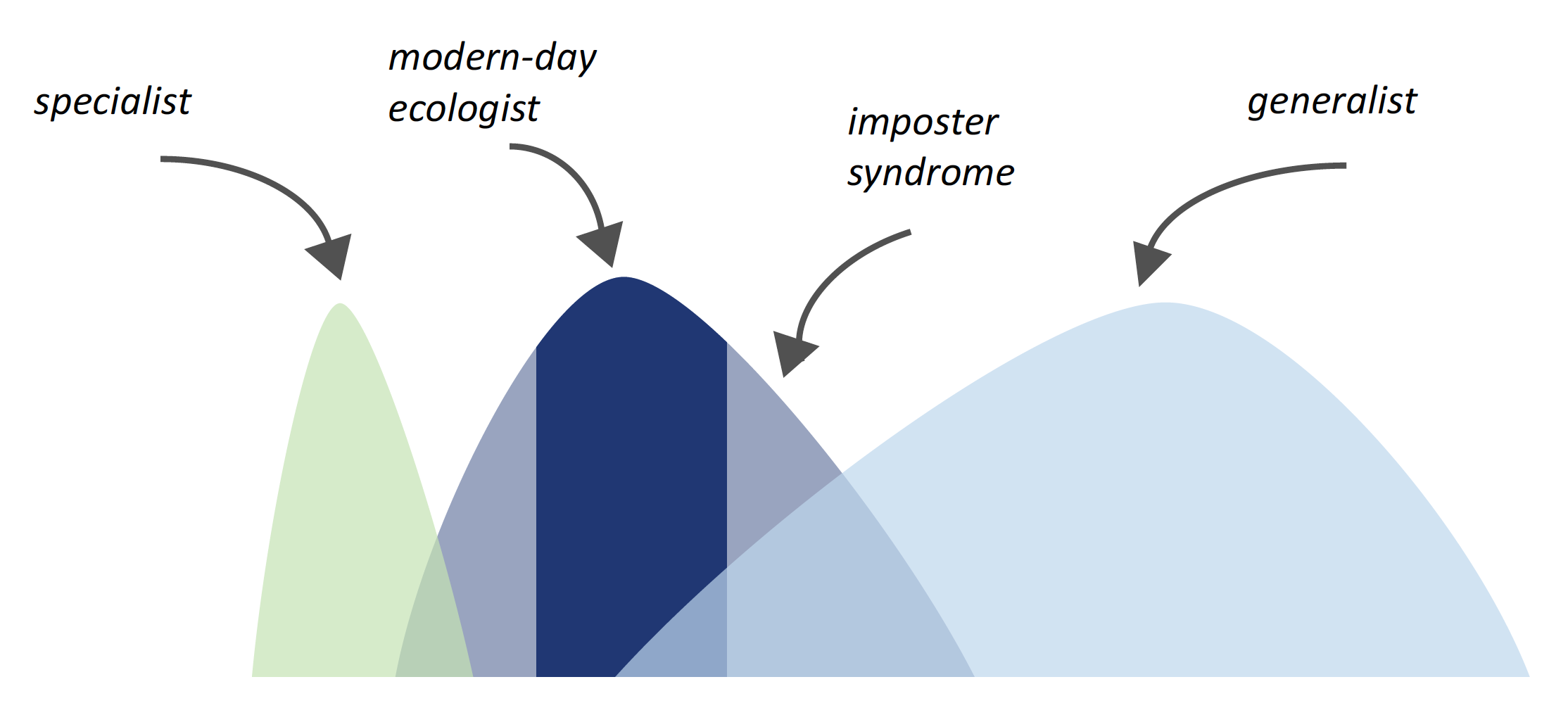

In ecology, we are taught that an organism either fills a particular niche, and is a specialist, or adopts a strategy of being able to occupy several niches, making it a generalist (think the raccoons going through your trash). The modern-day ecologist needs to find a middle ground, occupying a specific niche, but being able to lightly/poorly use additional ones (Figure 1). Most would agree that completing a PhD is an exercise in becoming a specialist. But, in a sense, if it prepares you for ‘real-world’ research, it’s an exercise in being both partly a specialist and partly a generalist. If we are to learn from the basic principles of our field, we should accept that we can’t be specialists in many domains, and we will therefore feel below average in at least some of the many areas we work and explore in our research. It follows that if we are constantly edging into new areas in and outside of our primary field/niche, we will experience imposter syndrome.

Figure 1. Broadly, organisms vary from specialists to generalists. The modern-day ecologist exhibits an intermediate state, with a specialty in one domain, but active participation in other domains. Participation in these other domains leads to imposter syndrome.

Almost every other day I wonder if I’m prepared enough and if I’m just here as the result of a cruel sequence of accidents. Am I seriously supervising other students? Why am I terrible at chemistry? Is it ok that I still google stats? Did they accidentally give me that grant? It has become obvious to me that it’s not just me, but many of my peers that feel this way - but why? Feeling imposter syndrome may be the inevitable result of being an ecologist today, but several defining features of academia and the world of research exacerbate this sense of doubt and even guilt around it. Here are some features of life as a researcher in academia that seem important to me to understand the origins and maintenance of imposter syndrome:

Academia lacks positivity.

Let’s face it, academia is not inherently positive. We get rejected from applications, get rejected from some more, criticized for dozens of pages in response to paper submissions, and the entire process of moving up in the research hierarchy involves lots of proving ourselves (and being judged). I understand why, theoretically and ideally, all this pushing back and criticism, including our own, is meant to make us honest, think about our work in different ways, and ultimately improve the quality and impact of our science. Even if that is true, we could do a better job of praising each other’s work before diving into the many comments and criticisms. A small start is finding a positive community, where people help celebrate the small things, and just letting others you work with know how appreciative you are and how well they are doing. Or like me, have a partner that keeps a small bottle of Prosecco on hand to mini celebrate a paper submission, a lukewarm acceptance, or a successful sequencing run. Whatever this means for you, make it a priority to find and build these supportive environments.

We are asked to be too many people at once.

Maybe we are asked to be too many people at once, be great at too many things. This may be part of why we tend to experience some serious doubts about our skills. No one can be an expert across what is effectively the many jobs we are asked to do. Apparently, I should be a soil scientist, a microbiologist (nevermind that that spans several kingdoms), a charismatic presenter, a star people-person and trainer, a teacher, a master science communicator, and stellar science writer. These are literally some people’s entire profession. Personally, I think I’m good at the big picture questions, getting stuff done (aka never taking no for an answer), and writing (don’t judge from my blogs...) - this is my dark blue zone. In contrast, I am pretty bad at showing my enthusiasm and my confidence could use some work (hey, imposter syndrome) – the larger transparent blue zone in the figure above. People are not great at everything, and it’s important to accept that this is fine.

We get to be many people at once.

Is this doubt just a consequence of the type of work we chose? I love being a researcher because I am constantly being challenged and growing. Research in itself is a quest to find what is not known. So, we’re all doing everything for the first time most of the time. For me, it’s energizing to switch between different lenses and foci, to try and fail. I love switching between different tasks, countries, and approaches. My days can go from getting attacked by chiggers in a tropical forest to coding on a computer; from getting kids to grow their microbes on plates to applying to a national grant; from guiding a student to asking for advice from a mentor. Ultimately though, we are each just one person, and we can’t specialize in everything.

Living with imposter syndrome.

As evidence of my high expectations, I just realized I wanted this paragraph to nicely solve imposter syndrome. Maybe we need to actively decide if the tradeoff between the amazing work we get to do and the inevitable consequence of doing a job that demands a diversity of roles - imposter syndrome - is worth it. Maybe it’s time to push back against the idea that a scientist should be great at it all at once. It’s ok if you aren’t passionate about outreach to middleschool children. I’m sure someone else loves doing that. That’s why we have communities and diversity within them. So, I think we should try new things, and be ok with failure and imperfection; we don’t have to make ourselves do it all. Ultimately, that is what many of us love about science, the freedom to explore and decide for ourselves. Instead of doing the impossible and solve imposter syndrome, I’ll echo many before me, and say it’s ok to feel like an imposter, and yes very normal as a scientist. But, maybe reflecting and understanding why this is so pervasive in research and in our own work, but also resetting expectations, will help us just be whoever we are, and be better at it than when we are bogged down by imposter syndrome.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in