Invadopodia and cooperative metastasis

Published in Cancer

EMT, invadopodia and leader cells

Breast cancer cells originate from breast epithelial cells. In normal breast tissue, epithelial cells are tightly connected to each other. However, as the breast cancer progresses, some cells start detaching from the tissue, and then freely moving through the tissue. The cells that can individually move are referred to as mesenchymal cells, and the process of detachment is called Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Some cancer cells also make invadopodia, small protrusions that help cancer cells make holes in the matrix, so they can move through dense spaces. It was always assumed that invadopodia exists only in mesenchymal cells, but we now show that cells can be quasi-epithelial, and moving as a group, while at the same time making invadopodia for the group to pass through tight spaces. Interestingly, for a group to move, it is sufficient for the leader cell, positioned at the front of the group, to make invadopodia.

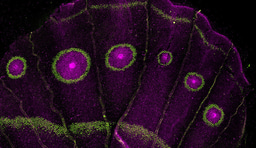

Spheroid made up of invasive cells with invadopodia (magenta) and non-invasive cells (green), is cooperatively invading into the surrounding matrix.

Cell sorting and cooperative invasion

We wondered what would happen if we mix a bunch of cells that are unable to make invadopodia and move i.e. invade through tight spaces, with a few cells that can make invadopodia. We formed a ball out of this cell mixture (a.k.a spheroid) and placed the spheroid in a really dense matrix. We used collagen as the matrix that best mimics breast tissue, and colored non-invasive cells green, and invasive cells in purple.

What happened then? All the purple, invasive cells reorganized and went right to the edge of the spheroid, while the green ones were just randomly moving within the circle. This created a beautiful purple ring around the green circle, in which purple cells were all in direct contact with the matrix. In the next step, purple, invasive cells started digging the surrounding matrix, and making tunnels. And finally, non-invasive, green cells followed. We refer to this phenomenon as cooperative invasion, where the invasive purple leaders enable the non-invasive, green follower cells to move and through the dense environment.

Invadopodia in leader cells is crucial for cooperative invasion, and removing the main invadopodia protein Tks5 stops cooperative invasion. Another crucial component is the attachment among cells. If we remove the main protein that keeps cells together, E-cadherin, purple cells start invading and moving individually, not as the collective. And the possibility of cooperative invasion disappears.

Cooperative invasion and metastasis in vivo

To make our final conclusions applicable to real tumors as they occur in patients, we have used our cells to form tumors in animal models. Here, our data showed that cells with invadopodia metastasize to the lung, while if we remove invadopodia via stopping Tks5 protein expression, cells stop metastasizing. Now, if mix cells with and without invadopodia, cooperative metastasis occurs. The cooperative metastasis, similarly to invasion, is dependent on both Tks5 and E-cadherin presence in leader cells, but also E-cadherin presence in follower cells. If E-cadherin is absent from either leaders or followers, they won’t adhere to each other and form a group, and won’t be able to move through the body together or cooperatively metastasize.

A small number of cells with invadopodia (purple) lead invasion and metastasis of non-invasive cells (green). Created with BioRender.com.

Conclusion

In summary, this work shows that invadopodia formation in quasi-epithelial cells is even more dangerous than when they form in mesenchymal cells. Namely, when invadopodia forms in a mesenchymal cell, that cell can metastasize. However, quasi-epithelial cells can form groups with non-invasive cells that cannot otherwise metastasize. In such cells, invadopodia formation can enable cooperative invasion and cooperative metastasis of many, many more cells. This is, in turn, way more detrimental for the patient, shortening survival.

Fortunately, this also brings hope that metastasis can be prevented by targeting only invadopodia, which forms in just a few leader cells. Specifically targeting the rare cell population is likely to cause less side effects compared to targeting the whole tumor mass.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in