Is inflammation a treatment target for suicide risk?

Published in Immunology and Anatomy & Physiology

Suicide is an ongoing public health crisis. More than 700,000 people die by suicide each year, which accounts for 1 in 100 total deaths worldwide, according to the World Health Organization.

Suicide risk has emotional, cognitive, social and biological roots. Although anyone can experience depression or suicidal thoughts, certain factors have been linked to increased risk of acting on these thoughts, such as socio-economic influences, being male, childhood trauma, and mood disorders, such as major depressive disorder. Genetics and epigenetics also play a role, and specific risk genes are beginning to be identified using the very large data sets from the Psychiatric Genetics Consortium. Likewise, a growing number of studies, including previous work from our teams, have linked nervous system inflammation to increased suicide risk. Some genomic data also implicates inflammation and immune response systems.

What’s missing, however, is a clear picture of specific changes in the brain associated with suicide risk. Which genes are activated and which genes show diminished expression? Which inflammatory pathways are at play? How are brain cells impacted?

And perhaps most importantly, can we translate answers to these questions into improved strategies for evaluating and reducing suicide risk?

Identifying drivers of brain inflammation and their association with suicide risk

To find answers, we conducted RNA sequencing and DNA methylation sequencing on brain tissue from 29 people who died by suicide and 32 controls that died suddenly from other causes. Major psychiatric illness was ruled out through SCID interviews with significant others and family members.

Critically, the people who died by suicide in the study were selected because they were largely free of antidepressant and antipsychotic medications at the time of death; this is important because such medications may mask biological markers of suicide risk. To our knowledge, this is the first time such extensive methylation and transcriptomic analyses have been conducted in this population.

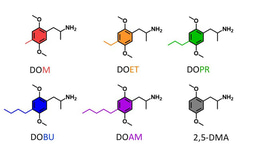

Our results, published in Molecular Psychiatry, identified increased inflammation in the brains of people who died by suicide compared to people who died by other causes. We also pinpointed several inflammatory pathways that are overactive in people who died by suicide while key protective mechanisms were less active. Specifically:

- The gene NPAS4, which regulates inflammation and helps maintain the integrity of brain cells, is less expressed, or active, in the brain of people who died by suicide. This reduced activity may enable increased inflammation and, if so, suggests that some people with suicidal ideation may be vulnerable to increased inflammation.

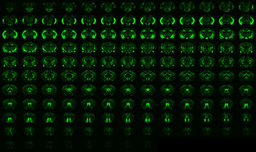

- Multiple molecular pathways associated with inflammation in the brain are overactive in people who died by suicide.

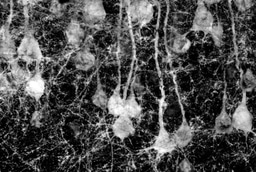

- There are fewer oligodendrocytes, which are cells that protect the brain’s nerve fibers, in the brains of suicide decedents. Loss of these critical cells may be linked to increased inflammation.

- There is increased excitotoxicity in the brain in suicide decedents.

- We identified 40 differentially methylated regions that mapped to seven inflammatory genes in the brains of suicide decedents versus controls who died by other causes.

Taken together, our findings provide a nuanced look into the complex, intertwined biological factors that drive brain inflammation and are linked to suicide. They also highlight an important opportunity to develop new, evidence-based strategies for separating harmful from helpful inflammation in at-risk individuals, which could one day potentially help save lives.

What’s next?

Right now, when someone visits a medical center or mental health clinic, physicians do not have an objective way to evaluate suicide risk. Treating inflammation also currently is not an approved way to mitigate suicide risk. But what if these tools were available?

This is the future we’re working toward, one in which a simple blood test can help assess risk by measuring suicide-associated markers in the blood and provide physicians with evidence-based regimens to reduce aspects of inflammation that impact suicide risk.

It’s a long road, but we are making progress.

In addition to our recent Molecular Psychiatry study, which we hope will inform new treatment strategies, we have been searching for blood biomarkers of suicide risk — and finding promising leads.

In a 2022 Translational Psychiatry study, we identified a set of immunobiological markers in the blood that predicted the future development of depressive symptoms in pregnant women with high accuracy. Nearly one in five new mothers experience severe depression during or after pregnancy, and about 14% have suicidal thoughts. Additional work is ongoing; currently, we are analyzing these predictive biomarkers in a population of 130 non-pregnant patients (men and women) in a study of suicidal behavior over one year to see if these findings generalize to other groups of people.

We need additional strategies to expand our therapeutic toolkit for suicide risk and ensure we are addressing suicide risk from all angles. The more we can learn about inflammation and the ways in which it impacts suicide risk, the better equipped we will be to help people when they need it most.

The confidential 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline is free and available 24/7 by dialing or texting 988.

On behalf of our research team, we thank the families of the deceased participants for their donation of brain tissue and sharing of clinical information.

Research reported in the Molecular Psychiatry article was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award no. R01MH118211 (Brundin, Mann and Achtyes). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Research reported in the Translational Psychiatry article was supported by Van Andel Institute, Pine Rest Christian Mental Health Services and the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award no. R01MH104622 (Brundin). The clinical trial identifier is NCT02566980. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Follow the Topic

-

Molecular Psychiatry

This journal publishes work aimed at elucidating biological mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders and their treatment, with emphasis on studies at the interface of pre-clinical and clinical research.

Ask the Editor - Immunology, Pathogenesis, Inflammation and Innate Immunity

Got a question for the editor about the complement system in health and disease? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in