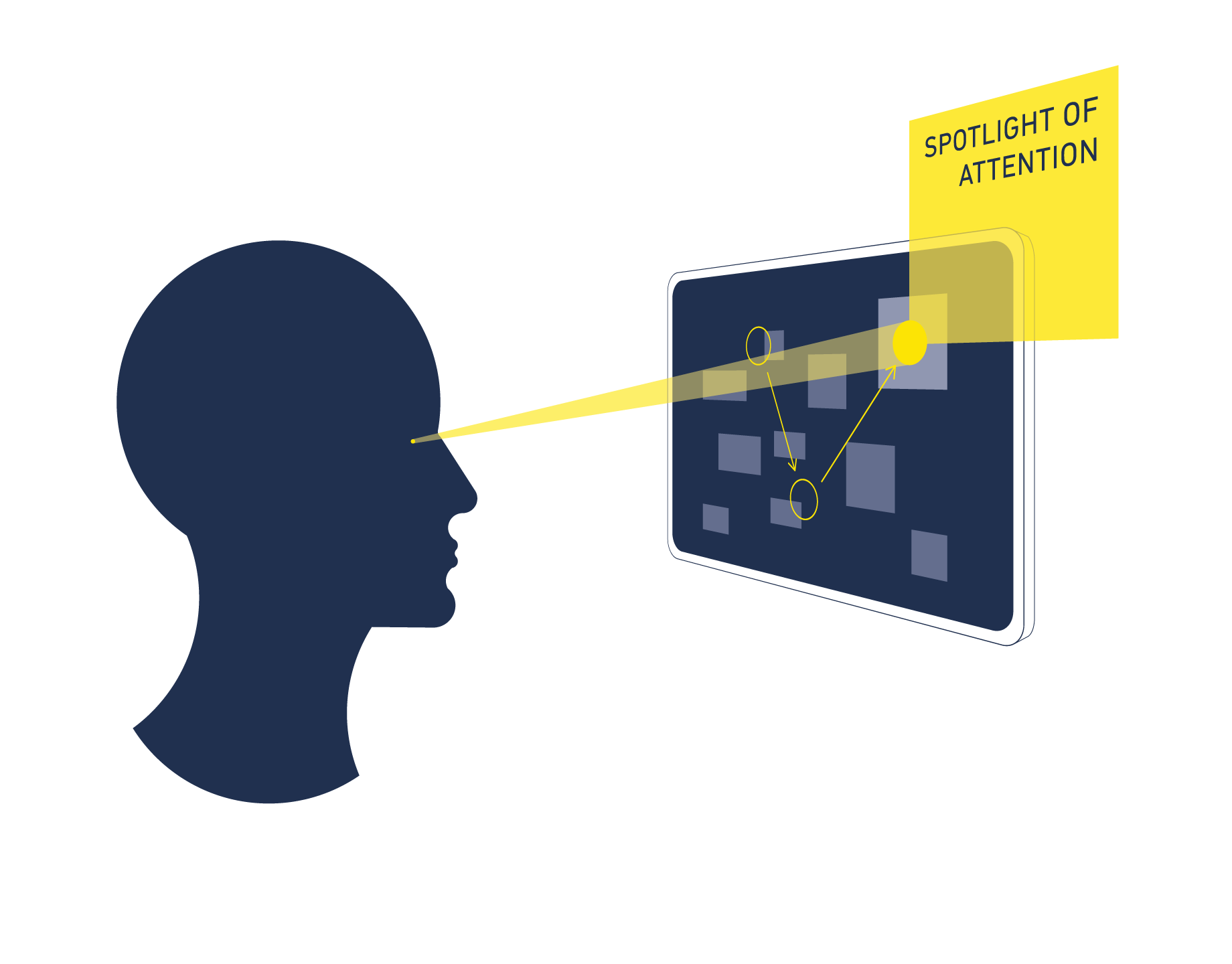

We frequently urge our students (and ourselves!) to “pay attention”, but what do we really mean by this phrase? The notion of ‘paying attention to’ an object creates an impression of attention as a resource which we have at our disposal, ready to be deployed (or not) at our command. This is reinforced by the numerous metaphors we have for the concept (a filter, a spotlight, a zoom lens, even a glue). In all of these metaphors attention is cast in the role of a ‘tool’ for us to use. Going a level deeper, such metaphors all take for granted a reified concept of attention, i.e. that attention is a real, measurable ‘thing’. Increasingly in the academic study of attention, however, there is some opposition to these traditional notions of what attention is. These can generally be summarised as an effort to recast attention as an effect rather than a cause (e.g. here, here and here, amongst others).

I think that this seemingly niche academic debate actually has some interesting implications for educators. Thinking of attention as an effect rather than a cause can throw a new light on the understudied problem of attention in schools, and what teachers can do about it.

What’s the problem?

There are two main problems with the metaphors which reify attention as a resource, one logical and one practical. The logical one (which is of less relevance perhaps to educators, but still useful for fans of logical validity), is that the evidence for these models of memory often rest on circular arguments. For example, if we take the metaphor of attention as a flashlight, imagine the following dialogue, taken from this paper by Vince Di Lollo

Person A: a stimulus flashed at a location just ahead of a moving object is perceived more promptly and more accurately.

Person B: why is that?

A: because the attentional spotlight is deployed to that location, and stimuli presented at an attended location are processed more promptly and more accurately.

B: and how do we know that attention has been deployed to that location?

A: we know it because stimuli presented at that location are perceived more promptly and more accurately.

The practical problem is that metaphors such as this place the burden for the control of attention firmly on the student themselves, to deploy as their preferences or abilities allow. Now I am in no way arguing that students are not capable of exercising control over their attention, nor that teachers should be held responsible when a student’s attention wanes; indeed I would strongly repudiate this. I do think, however, that a model which casts attention as a resource of the student is unhelpful to teachers. Teachers looking to improve student performance using this model are left with few options, other than perhaps brain training (so far unimpressive) or vague appeals to a student’s better nature (“direct your attention towards this pleeeease”).

Attention as an effect not a cause

Far more productive for educators would be the discussions arising from seeing attention as an effect, rather than a cause. This reconceptualisation naturally invites the consideration of

- which conditions are most likely to engender the effect of focused attention?

and importantly…

2. which information should we create these conditions for?

Again, this suggestion in no way denies that students are causal agents in their own behaviour, merely that teachers will be more empowered by a focus on the conditions that they can create whereby attention emerges as an effect.

I will look at each of these two questions in turn.

Which conditions are most likely to engender the effect of focused attention?

Decades of careful psychological work in dark laboratories has helped to confirm a lot of common sense notions about how attention can be captured (e.g. by bright colours, unexpected shapes or other features which stand out, stimuli which move or loom, motivation, meaning, reward and so on.) If these features are present in the task, we are generally more able to focus on that task. If they are present in a stimulus which is not part of the task, then we are more likely to be distracted.

So far so good; as teachers we need to try to make our stimuli as salient as possible and reduce other distractions. However this apparent simplicity leads us on to the second, less commonly considered implication of considering attention as an effect; if we can create the conditions to direct student attention, what information exactly do we want to create these conditions for? In other words (returning to the old metaphor for simplicity’s sake), what do we want student attention to be focused on?

Which information should we create these conditions for? Selecting the target of focused attention

Where attention is discussed in education, it tends to be focused on the ideas above, in terms of strategies for capturing attention. Indeed, the goal of my teacher training on this topic was entirely this, the creation of an attentive, engaged class. What exactly they should be engaged by seemed less of a concern. If attention could be attracted by the teacher, then learning was assumed to be an inevitability.

Sadly this position is mistaken. I have written before of the limited capacity ‘bottleneck’ of attention. This limited capacity means that only a tiny fraction of information arriving into our perceptual systems will ever be processed to a meaningful degree. Therefore whilst an attentive class can clearly be a step in the right direction, they will only be learning efficiently if we as educators ensure that their attention is focused precisely on the stimuli that we want it to be. Just as becoming distracted by low level disruption from other students may inhibit learning, so will engaging with superfluous material presented by the teacher. If attention is the result of creating the right conditions, then we need to be very clear about exactly what is worth creating those conditions for.

Take the case of powerpoint slides. I spent many hours early in my teaching career crafting aesthetically pleasing powerpoint slides. My backgrounds were salient, full of nice bright colours. Some of the words zoomed in from the side of the screen. Text was often accompanied with a picture (or even a gif if I was feeling particularly creative), usually humorous and tangentially related to the main information. Looking back, especially through the lens of considering attention as an effect and questioning where I was encouraging that effect to occur, is sobering. My salient features were either surface level features (the movement of the text rather than its content) or entirely irrelevant to what I wanted the students to know (the background and the pictures). I was actively inviting attention to be directed away from that which I thought was most important. This is why important and potentially impactful strategies such as dual coding, which combine visual and verbal materials (and which has been valuably popularised recently by figures such as Oliver Caviglioli), need to be treated with caution. Bad dual coding is not just ineffective, it leads to split attention or outright distraction.

Deciding on the right targets for our students’ attention is a challenge that cuts right across education, from the pedagogical issue of how best to deliver information to the curricular decisions required to identify precisely what it is that we want students to know in the first place. I have been delighted to see an increased focus on curriculum amongst teacher networks as a result (e.g. here, here and many great posts here for example, though to my knowledge the specific link between the importance of curriculum design and attention has not be explored either in blogs or research).

A new way to view attention in the classroom

Viewing attention as an effect makes us value it (and the contribution that we can make to it) more. It makes us consider more carefully how to attract attention, but crucially also what we want to attract attention to. Capturing attention is not in itself the aim. The goal is to provide the optimal conditions so that attention is captured by the exact stimuli that we have identified as most valuable. I have tried to argue here that this process may be assisted if we define attention less as a cause of student behaviour and more as an effect of the conditions that we put in place.

Note:

This post was taken from one appearing on my personal blog

References:

Anderson, B. (2011). There is no such thing as attention. Frontiers in Psychology, 2(SEP), 1–8. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00246

Di Lollo, V. (2018). Attention is a sterile concept; iterative reentry is a fertile substitute. Consciousness and Cognition, (February), 0–1. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2018.02.005

Eisenreich, B. R., Akaishi, R., & Hayden, B. Y. (2017). Control without controllers: toward a distributed neuroscience of executive control. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 29(10), 1684–1698. http://doi.org/10.1162/jocn

Krauzlis, R. J., Bollimunta, A., Arcizet, F., & Wang, L. (2014). Attention as an effect not a cause. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(9), 457–464. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.05.008

Follow the Topic

Your space to connect: The Psychedelics Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology, and Neuroscience!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in