Laboratory capacity building during COVID-19 in Somalia: improving access to essential diagnostics for national health security in a fragile setting.

Published in Biomedical Research

The COVID-19 pandemic is remembered as a disease that has shaken the tenets of global health in a significant way. For over three years, from 2020 to 2022, it dominated as the leading cause of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths due to infectious disease, bagging the infamous title of the blockbuster virus of the decade. However, amidst the devastation, the pandemic exposed the underbelly of health security, exposing the gaps in preparedness, response, and recovery.

Additionally, due to limited countermeasures available in the early phase of the disease, testing and tracking infected individuals become the only available weapon to curtail transmission. This situation placed laboratories, a traditionally neglected sector of the healthcare system, at the center of the response. Indeed, it was time for the laboratory system to emerge from its neglect and assert its essential role in the health security landscape. While countries capitalized on this opportunity to develop their laboratory sectors, it was a particularly valuable opportunity for nations facing resource limitations and ongoing conflicts.

For the Federal Republic of Somalia, the scale-up of the infrastructure and health workforce capacities, along with the provision of state-of-the-art equipment and supplies achieved during this period, was unprecedented compared to any previous intervention from the government, humanitarian/development partners, or the private sector. These efforts were essential to expand access to testing for the population living in diverse settings, some of which were inaccessible due to insecurity. It was deemed important to share this experience through a scientific publication as a successful health program case study and to set a precedent for countries in similar contexts. Therefore, our articles illustrate how the opportunity was effectively utilized to transform the country’s laboratory system showing key milestones in the laboratory sector.

While similar narratives have emerged from other nations, such as Yemen, the context in Somalia differed fundamentally in several respects, some of which are described below:

Starting from scratch

Since the country is emerging from three decades of internal civil conflict, the central government continues to struggle to fulfill its statutory obligations, including providing essential healthcare. As a result, healthcare infrastructure is severely damaged due to years of neglect, the demand for services is overstretched, and the health workforce has limited capacity. Functional laboratories in the country were few and far between, making establishing capacities, especially at the State level, quite challenging owing to the lack of basic amenities like water and electricity.

The nightmare of non-state actors

The laboratory improvement program faced particularly significant challenges because it targeted a third of the population living in the precincts of de facto Non-State actors. Implementing health programs and testing services to hard-to-reach populations sometimes exposed us to risks. Ultimately, achieving the goal outweighed the fear, and the results justified the calculated risks.

Co-occurring health emergencies

The COVID-19 pandemic coincided with persistent outbreaks in the country, such as cholera and measles, which often diverted resources and focus, impeding implementation. Despite this, the global attention on COVID-19 at that time ensured that interventions to address the pandemic remained a top priority.

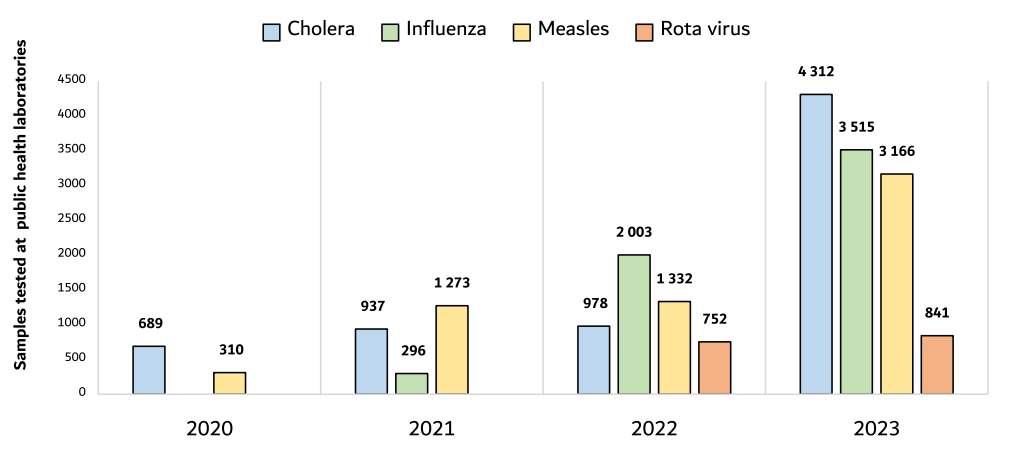

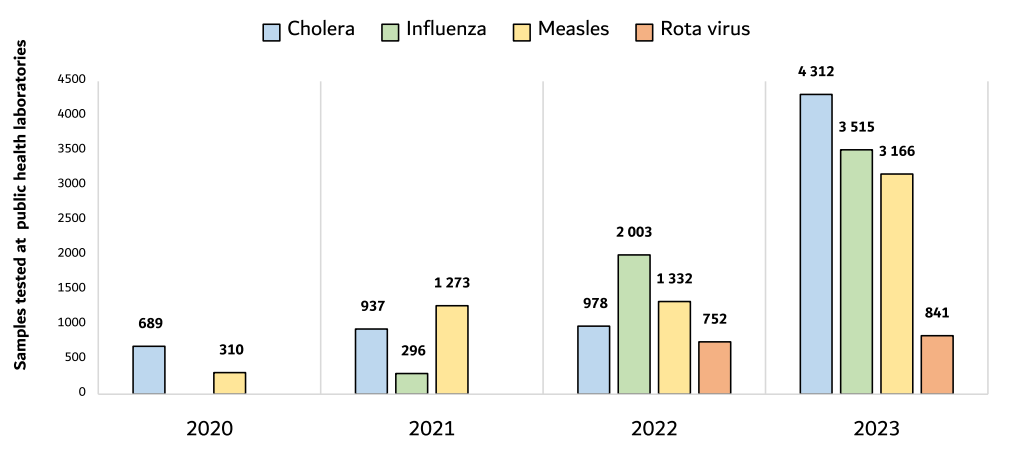

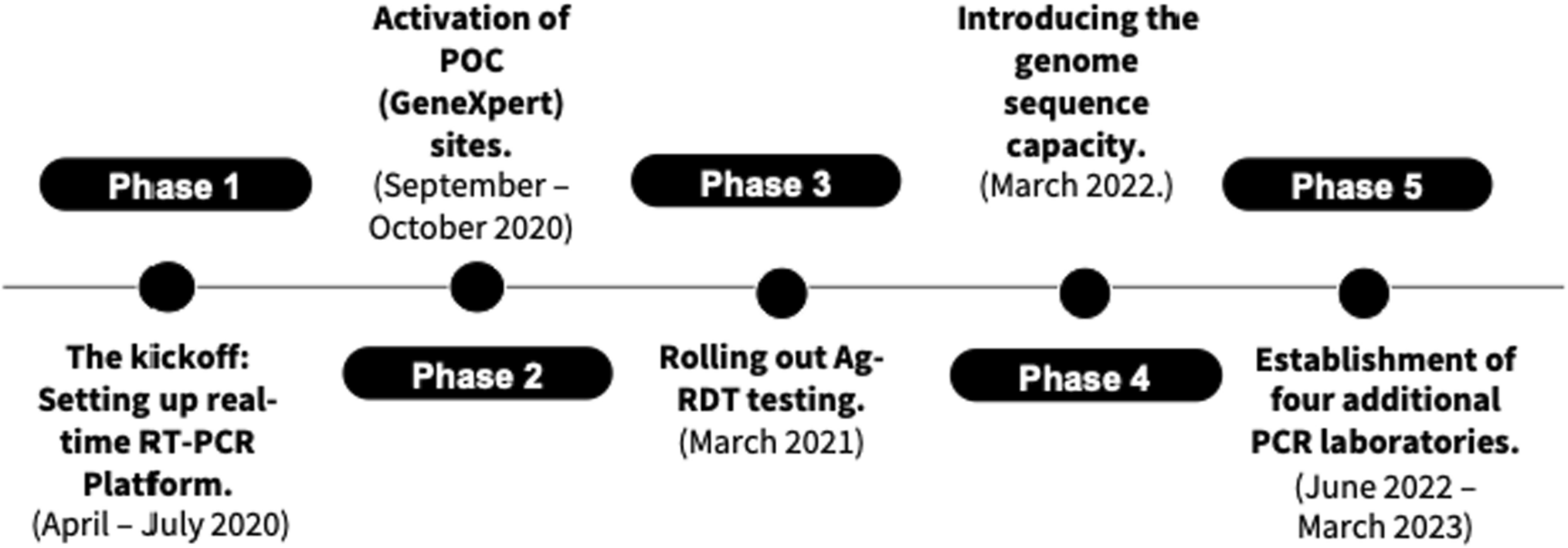

Of the many achievements reported in the paper related to laboratory and surveillance improvements, two main areas deserve a mention. First, laboratory capacity for molecular, bacteriological, and serological testing has been significantly expanded and improved to enhance surveillance of outbreak-prone diseases in the country. This development strategically positions the country’s public health laboratories on the road to recovery from many years of neglect. It also improves the country’s IHR core capacity and health security index score. Figure 1 below shows the progressive improvement in the number of tests for different endemic diseases.

Figure 1: Showing the number of tests for different endemic diseases performed in public health laboratories between 2020 and 2023.

Second, establishing three genomic sequencing laboratories represents a transformative step toward access to innovative technologies, even in resource-limited settings. For countries reliant on humanitarian agencies for essential health programs, such as immunization programs, this kind of investment would typically be unfeasible during peacetime. However, the urgent necessity for in-country capacity to monitor circulating variants and the limited ability to refer samples outside the nation have underscored the importance of developing substantial local capabilities.

Next steps:

Establishing the infrastructure and installing the equipment are only a few pieces of the puzzle. The major task will be to sustain the progress and ensure the provision of the resources required to maximize the utilization of the established capacity. As interest in COVID-19 waned, complacency has already set in. However, to fill the gaps and ensure the functionality of this investment, leadership and prioritization in resource allocation will be required both at the MOH level and in critical health programs such as WHO.

In conclusion:

The COVID-19 pandemic was a lifetime opportunity for resource-limited, humanitarian-dependent countries to improve their laboratory systems. As reported in our article, this opportunity was well utilized in Somalia. The material infrastructure and human capacity built will be a national asset that will be useful for the generations to come. The lesson learned from COVID-19 should be a wake-up call for countries to prioritize investment in their laboratory systems for the safety and security of their population and as the first line of defense against infectious diseases. In the meantime, laboratory strengthening programs should be viewed as a critical and indispensable part of the healthcare system, even in the context of emergencies and resource limitations. Moreover, resources should be deliberately planned and allocated to ensure continuous improvement while sustaining the gains.

Parting shot—As leaders assemble for the World Health Assembly in Geneva between May 19th and 27th, 2025, to discuss global health issues, the role of laboratories in ensuring health security should be a standing agenda item followed by actionable resolutions. Indeed, the world should not wait for the next pandemic to realize the critical role laboratory programs play in ensuring health security for all.

Follow the Topic

-

Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health

The journal aims to impact global epidemiology and international health with articles focused on innovative scholarship and strategies to advance global health policy.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Infectious disease outbreak in conflict-driven displacement: challenges, responses and future

Infectious disease outbreaks are increasingly entwined with conflict, forced displacement, and fragile health systems. In recent years, cholera in Yemen, measles among displaced Rohingya, and COVID-19 in Syrian camps have revealed how conflict-driven migration and humanitarian crises amplify the risks of large-scale epidemics.

Overcrowding, collapsing health infrastructure, disrupted supply chains, rise of anti microbial resistance (AMR) and constrained access to care create fertile conditions for rapid transmission, particularly among migrants and refugees.

Despite growing recognition of these intertwined vulnerabilities, evidence remains fragmented, and the operational and policy frameworks required to mitigate these crises are often reactive rather than anticipatory. This collection aims to consolidate case studies, field data, and solutions to better understand, prepare for, and respond to infectious disease outbreaks among displaced populations in conflict-affected settings.

Key Topics

1. Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases in Conflict Settings:

• Burden and patterns of infectious diseases (e.g., cholera, tuberculosis, malaria, measles, and respiratory infections) in conflict-driven displacement.

•Transmission dynamics in over-crowded camps, urban conflict settings, and transit corridors.

•Impact of armed conflict and forced displacement on AMR dynamics.

•Case studies from acute and protracted conflicts (e.g., Syria, Yemen, Sudan, and Central African Republic).

2. Vulnerabilities of Forcibly Displaced Populations:

•Health disparities caused by malnutrition, poor sanitation, and disrupted care.

•Gender, age, and disability-related vulnerabilities in accessing health services.

•Access to care barriers due to security risks, mobility, legal status, and cultural challenges.

3. Health System Collapse and Humanitarian Responses:

•Impacts of weakened health infrastructure, fragmented governance, and security constraints on disease control.

•Strategies for disease surveillance, vaccination campaigns, and WASH interventions in volatile environments.

•Innovations in service delivery: mobile clinics, telemedicine, and community-led response models.

•Role of local actors and international humanitarian organizations in outbreak response.

4. Policy, Law and Future Preparedness

•Intersection of human rights law, refugee law, and international health regulations in managing outbreaks.

•Challenges in cross-border coordination, governance, and resource mobilization.

•Policy recommendations for anticipatory action and resilient health security systems in conflict and displacement settings.

All submissions in this collection undergo the journal’s standard peer review process. Similarly, all manuscripts authored by a Guest Editor(s) will be handled by the Editor-in-Chief. As an open access publication, this journal levies an article processing fee (details here). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 26, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in