Lung involvement in rheumatoid arthritis: what do we know?

Published in Public Health

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a highly prevalent heterogeneous group of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases with chronic and multisystemic physiopathogenesis involving several organs. Interstitial pneumonia has emerged as the most prevalent manifestation, affecting up to 60% of patients and, in some cases, preceding joint symptoms. The effectiveness of treatments varies, with specific disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) showing potential for controlling pulmonary symptoms. Early diagnosis and tailored treatment strategies are crucial for the effective management of RA-related pulmonary diseases.

RA can affect all compartments of the thorax, including the pulmonary parenchyma, large and small airways, pleura, and, less frequently, vasculature. Lung involvement typically occurs approximately five years after the diagnosis of RA, and few respiratory symptoms may precede the onset of joint symptoms.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is the most common manifestation of pulmonary involvement, with a prevalence of up to 80% reported via biopsy. Some cases may progress to pulmonary fibrosis and subsequent respiratory insufficiency, with implications for disease prognosis. Unfortunately, the incidence of ILD is underestimated, especially in the early stages of subclinical disease. Other pulmonary manifestations include airway involvement, pleural involvement, and rheumatoid pulmonary nodules. The pulmonary toxicity caused by drugs used to treat RA itself, including DMARDs, whether synthetic, or biological immunomodulators or so-called small molecules, is highly relevant. Synthetic drugs, mainly methotrexate (MTX), sulfasalazine (SSZ) and leflunomide (LFN), have been implicated in the onset of respiratory manifestations. The use of immunobiological therapies, such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (anti-TNF), has also been associated with the development or exacerbation of ILD in patients with RA.

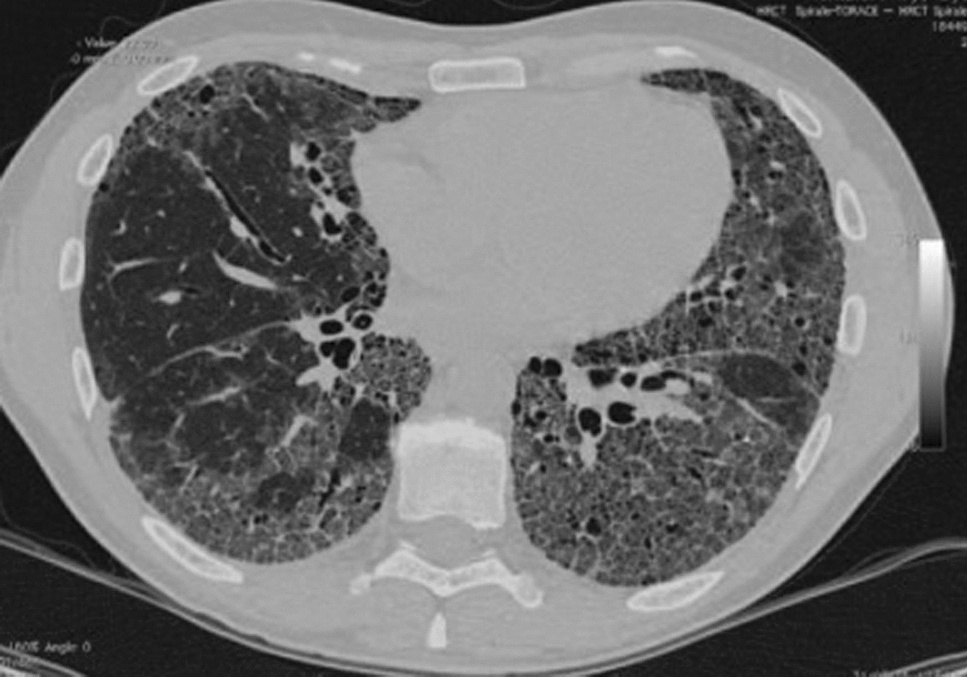

With more sophisticated radiological techniques, such as high-resolution computed tomography of the chest (HRCT), diagnosing pulmonary involvement in RA is more efficient, with tomographic findings predominating in approximately 55% of cases. HRCT identified interstitial pulmonary abnormalities and small airway involvement, most often in subclinical disease. The most common tomographic findings are the presence of pulmonary infiltrates with a predominance of ground-glass changes and septal and subpleural thickening, usually to a small extent.

Although RA is more common in women, ILD associated with RA (RA–ILD) occurs more frequently in men in the sixth decade of life. Some risk factors for developing RA–ILD are male sex, advanced age, smoking, high titers of antibodies to RF and/or anti-CCP, RA disease activity, decreased functional status, and the presence of other nonpulmonary extra-articular diseases, such as subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules. Genetic risk factors have also been identified in RA–ILD, including the MUC5B promoter variant particularly associated with the usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern and various rare variants in telomerase. Individuals with RA are nine times more likely to develop ILD than the general population. Only 10% of patients with RA–ILD exhibit respiratory symptoms.

Interstitial lung disease comprises a spectrum of histological types with different clinical and radiological patterns. There is a vast spectrum of pulmonary histopathology in ILD patients with RA, with classes according to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society classification system for idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. The most common histopathological types are usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) , nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), and organizing pneumonia (OP). Other patterns of pulmonary involvement in RA include macrophage interstitial pneumonia (desquamative), diffuse alveolar damage, and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia.

Once the diagnosis of RA has been established, the therapeutic approach is defined based on the joint symptoms. Unlike systemic sclerosis, where lung involvement is strategically investigated before treatment is defined, screening strategies for RA–ILD are not implemented unless respiratory symptoms are present. Because there are no established screening strategies, many of these approaches have been extrapolated to treating scleroderma or interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Pulmonary function tests and HRCT can be used as diagnostic measures, especially in patients with risk factors such as smoking and advanced age.

Because there is no completely established therapeutic approach, decisions should be based on the benefits and clinical presentation of each patient. In asymptomatic patients with nonprogressive ILD, treatment is conservative. There is no defined therapeutic approach and patients with UIP respond poorly to treatment. Patients with NSIP and OP patterns may respond more favorably to immunosuppressants; however, some patients present with mixed or unclassifiable patterns on HRCT, making disease progression and therapeutic response unpredictable.

Follow the Topic

-

Discover Medicine

This is a fully open access, peer-reviewed journal that supports multidisciplinary research and policy developments across the fields of medical and clinical science.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Gut Microbiome and Human Well Being

The human gut microbiome plays a critical role in maintaining health and modulating disease processes. Its composition evolves across the lifespan under the influence of diet, lifestyle, aging, and environmental exposures. Disruption of gut microbial balance—known as dysbiosis—has been implicated in the pathogenesis of various chronic conditions, including autoimmune, metabolic, neurological, and inflammatory diseases.

This Collection welcomes submissions that explore the mechanistic, clinical, and translational aspects of gut microbiota in human health, with particular interest in:

The gut–brain, gut–heart, gut–cancer, and gut–joint axes

Gut dysbiosis and its immunological and metabolic consequences

Microbial metabolites and host-microbiome interactions

Microbiome-based diagnostics, therapeutic interventions, and biomarkers

We invite contributions including but not limited to:

Original research articles based on clinical, in vivo or in vitro studies

Reviews summarizing recent advances or proposing new frameworks

Perspective or opinion pieces that highlight emerging concepts or challenges

This Collection aims to enhance our understanding of the gut microbiome's contribution to health and disease and to inspire microbiome-based strategies for improving human well-being.

Keywords: Gut microbiome; Gut-organ-axis; chronic diseases; 16S rRNA; metagenomics

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jul 01, 2026

Gender and Ethnic Disparities in Cardiovascular Health and Diseases

The global burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is alarming, with profound gender and ethnic disparities. Women are more likely to be underdiagnosed and undertreated, while ethnic minorities, including African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, American Indians, and those in underserved communities, bear a disproportionate burden of CVD. Socioeconomic factors, inadequate healthcare access, and cultural barriers exacerbate these disparities. These disparities are not only a reflection of biological differences but also encompass a complex interplay of social determinants, healthcare access, and cultural factors. Understanding these dimensions is crucial for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies aimed at mitigating cardiovascular health inequalities. To bridge these gaps, rigorous research, robust data collection, and effective dissemination of findings are imperative in identifying these drivers.

This Collection will provide a platform for experts to share their research, insights, and solutions to address these pressing issues. We believe this Collection will contribute significantly to the ongoing conversation on health disparities and inform strategies to reduce the burden of CVD. We invite researchers and scientists to submit their original work to our Collection focused on gender and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular health and diseases. This Collection will contribute significantly to our understanding of the complex relationships between gender, ethnicity, and cardiovascular health outcomes and provide valuable insights into the drivers of these disparities and inform strategies for improvement.

Topics of interest include, but are not limited to:

- Gender differences in cardiovascular disease prevalence

- Ethnic disparities in treatment outcomes

- Sociocultural influences on cardiovascular health

- Impact of social determinants on heart disease risk

- Community-based interventions for at-risk populations

Keywords: Cardiovascular Disease Disparities, Gender and Ethnic Disparities in Health, Healthcare Access and Outcomes, Cardiovascular Health Equity, Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Cardiovascular Disease

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 14, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in