May oxylipins make bacteria be out of their tree? A controversial preprint that will not be published

Published in Microbiology, Protocols & Methods, and Cell & Molecular Biology

In 2020, co-authors and I published a bioinformatic research [1] aimed to confirm statistical and phylogenetic association between lipoxygenases and emergence of multicellularity. We have found such a link, but also discovered another subset of lipoxygenase-carrying species. They were notable for unusual ecological versatility, broad host range, status of "emerging pathogens" and antimicrobial resistance. It was obvious that these bacteria deserve priority in the further analysis. I narrated about them in a post on this Community (later translated into Russian and formally published in Priroda journal [2]) and started maintaining a "pathogen blacklist" consisting of lipoxygenase-carrying human pathogens.

Meanwhile, I looked for a way to look deeper into the role of lipoxygenase in host-microbe interactions. It was evident that it deserves studying and may have great medical significance. Since all information about pathogenic and symbiotic properties of studied bacteria was available for us from published literature only, the most pure and simple option was to perform an in-depth literature review. However, a traditional review has no options to quantify crucial traits of host-microbe interactions in lipoxygenase-positive bacteria. Moreover, it offers only a limited set of tools to determine which trait is more important. Given this, I decided to reinforce the review with data science and data visualization tools and to perform data research. I have published the results in a preprint [3] — but it appeared to have no chance for a formal publication.

Network text analysis

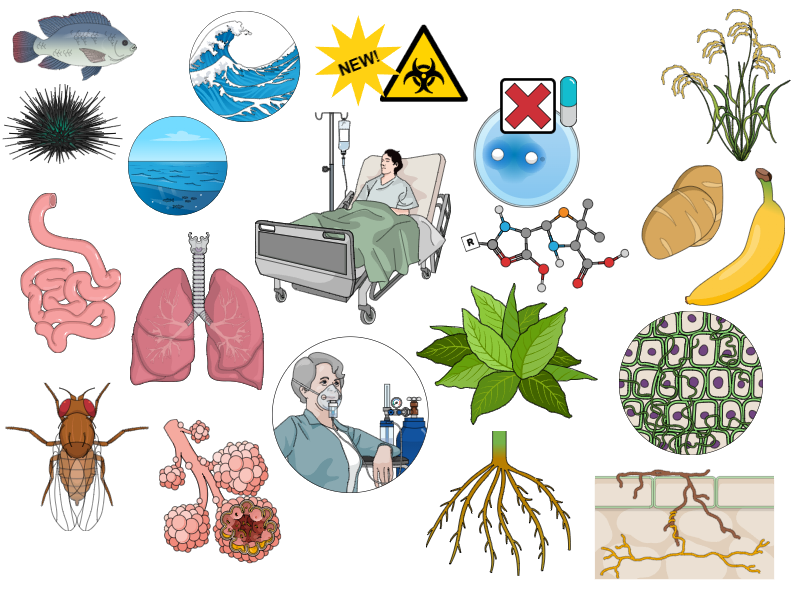

From the entire list of putative lipoxygenase-carrying bacteria (earlier created by BLAST searches), I took the bacteria for which any connection with a host (either in a parasite role or in a symbiont role) was characterized in literature. Thus, I obtained a list of putative lipoxygenase-carrying bacteria involved in any type of host-microbe interactions.

Then each species name in this list was used as a search query in PubMed, and for each query, the first ten found abstracts were used. From each abstract, I manually wrote out all words that characterized the ecology of bacteria used as a query. These terms included the characteristics of their hosts (e.g. “plant”, “human”, “banana”), diseases or conditions associated with infection or colonization (e.g. “lung”, “transplant”, “bacteremia”) or any other terms characterizing the host-microbe interaction (e.g. “endophytic”, “root”, “aquaculture”). So, I had a list of bacterial species with a list of ecophysiological terms for each of them.

This was the first controversial point of the study: in the text analysis, I extracted entities manually. This is really uncommon for data science: normally, entity extraction is performed with specific Python libraries such as nltk. However, fitting and teaching of resulting entity extractors would be comparable to manual extraction in terms of time spent given the relatively small size of my dataset. My extraction was knowledge-based in contrast to automatic blinded methods. This is the first methodological problem: knowledge-based methods allow to employ the researcher’s expertise, but are vulnerable to cognitive biases. Finally, I decided that using knowledge-based extraction is (at least) not worse than a systematic review. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are a gold standard for evidence-based medicine, and multiple clinical decisions are made on their basis — despite they inevitably include knowledge-based manual publication sampling. Thus, I used no automatic procedure for the entity extraction. However, the lack of automatic entity extraction confused some reviewers who expected an automatic procedure by default.

The lack of such procedure confused one of the reviewers who expected an automatic solution by default. They noted "the lack of validity test for the automatic classification" while no automatic classification was used.

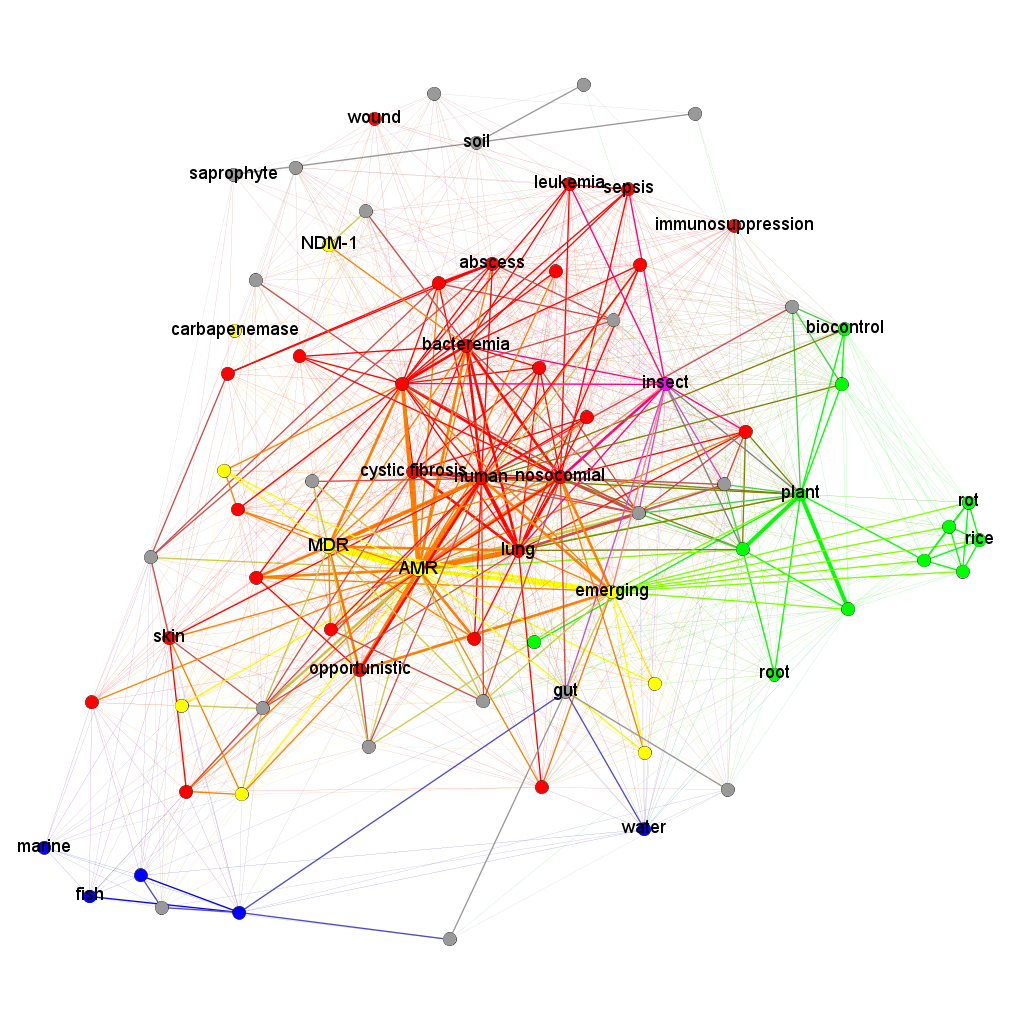

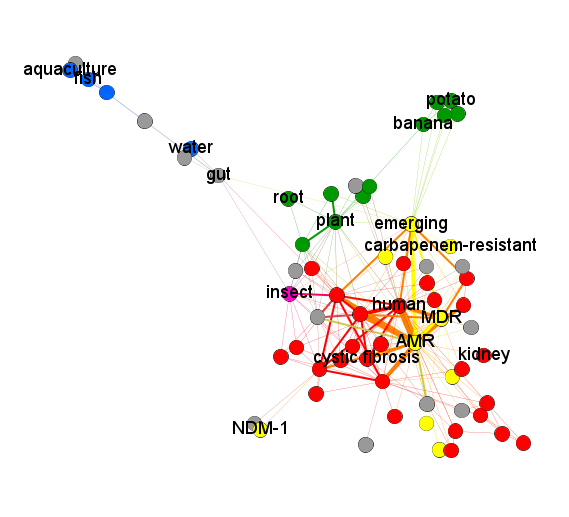

If the terms were my entities, a co-occurrence of entities was defined as a co-occurrence of two terms in the same species. The number of co-occurrences (the number of bacterial species in which these terms co-occur) was used as edge weights, while each term constituted an edge node. Edge weights were depicted as edge widths. So, I visualized the set of scientific articles as a graph.

I don’t describe the detailed methodology of graph text analysis since it is already described in well-known manuals, such as Applied Text Analysis with Python [4]. There are just two exceptions — I used manual entity extraction instead of automatic one and used Gephi and Cosmograph for the graph construction instead of Matplotlib. In general, the network text analysis is widely used in reviews — for example, in a review on flower coloration [5].

In addition to generating a graph, I manually coloured it in Gephi according to the term category. I divided all terms into 4 categories:

-

“plant-related” terms reflecting that the host of the bacterium is a plant, e.g. “plant”, “banana”, “root”, “endophytic”. Color code of this group within the research is green;

-

“human/vertebrate-related terms” reflecting that the bacterium is associated with human and/or a vertebrate. Here belonged, for example, all clinical terms (eg. “cystic fibrosis”, “blood”, “kidney”). Color code of this group within the research is red;

-

“marine-related” terms reflected the association of a bacterium with an aquatic organism (e.g. “fish”, “aquaculture”). Color code of this group within the research is blue;

- “public health threat” group of terms reflected that the bacteria pose a threat to public health (e.g. “emerging”, “carbapenemase”, “AMR”, “MDR”). Color code of this group within the research is yellow.

This way, I obtained a coloured graph (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). Each edge of it reflects that the pair of traits (depicted by its nodes) can co-occur in the same species of lipoxygenase-carrying bacteria. Thus, each edge connecting the nodes of two different colours definitely reflects a distant host jump.

The first thing one can note on this coloured graph is high connectivity between its “green” and “red” parts. This means that both plants and humans/mammals are vulnerable to colonization with LOX-positive bacteria, and they can readily shift between affecting plants and affecting humans. The term “insect” — considered as a part of a separate group — was also tightly connected with them suggesting that LOX-positive bacteria are down with affecting an insect, too. In contrast, the “blue group” of terms was located peripherally. Host jumps between aquatic and terrestrial organisms appeared highly unlikely.

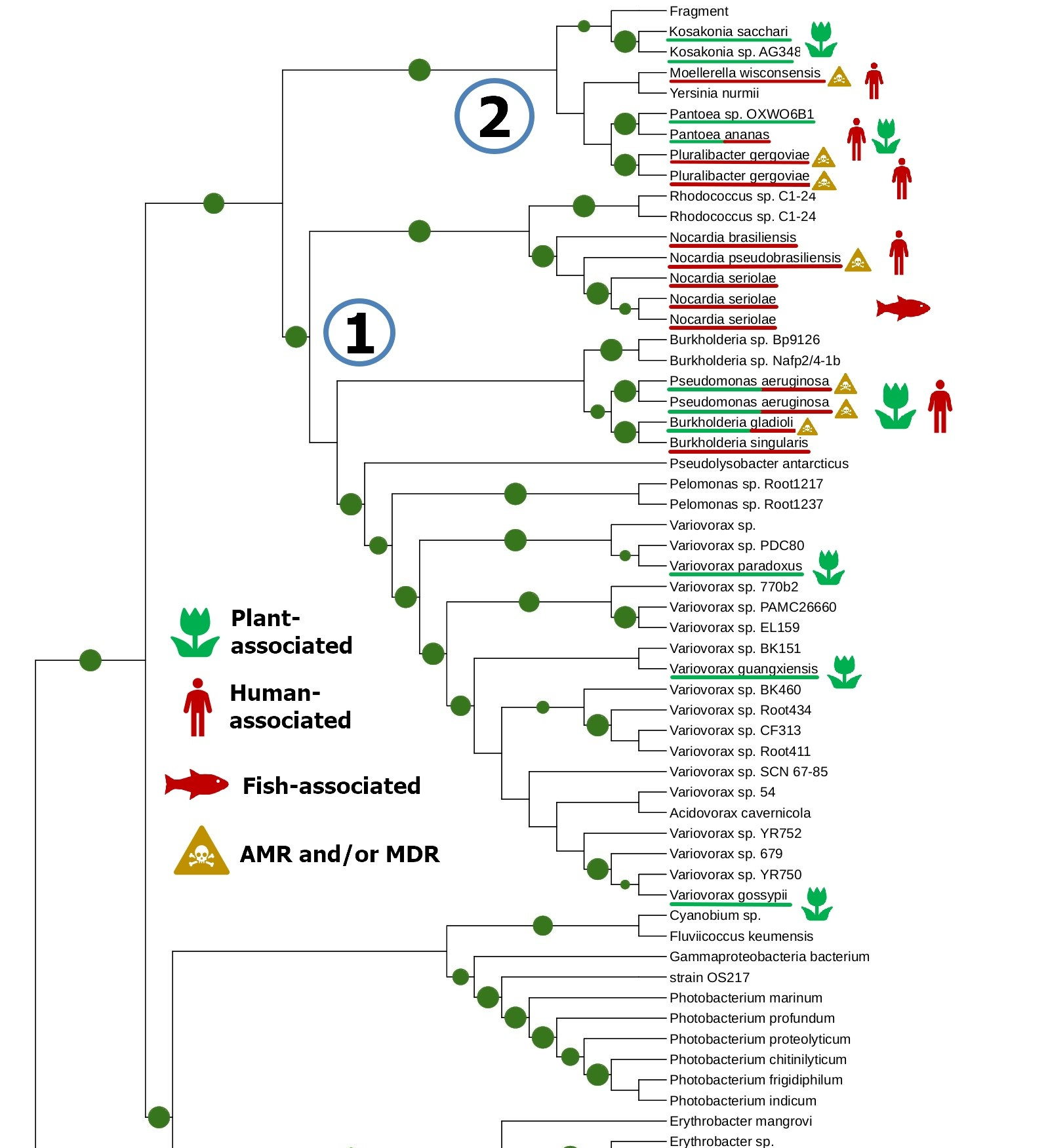

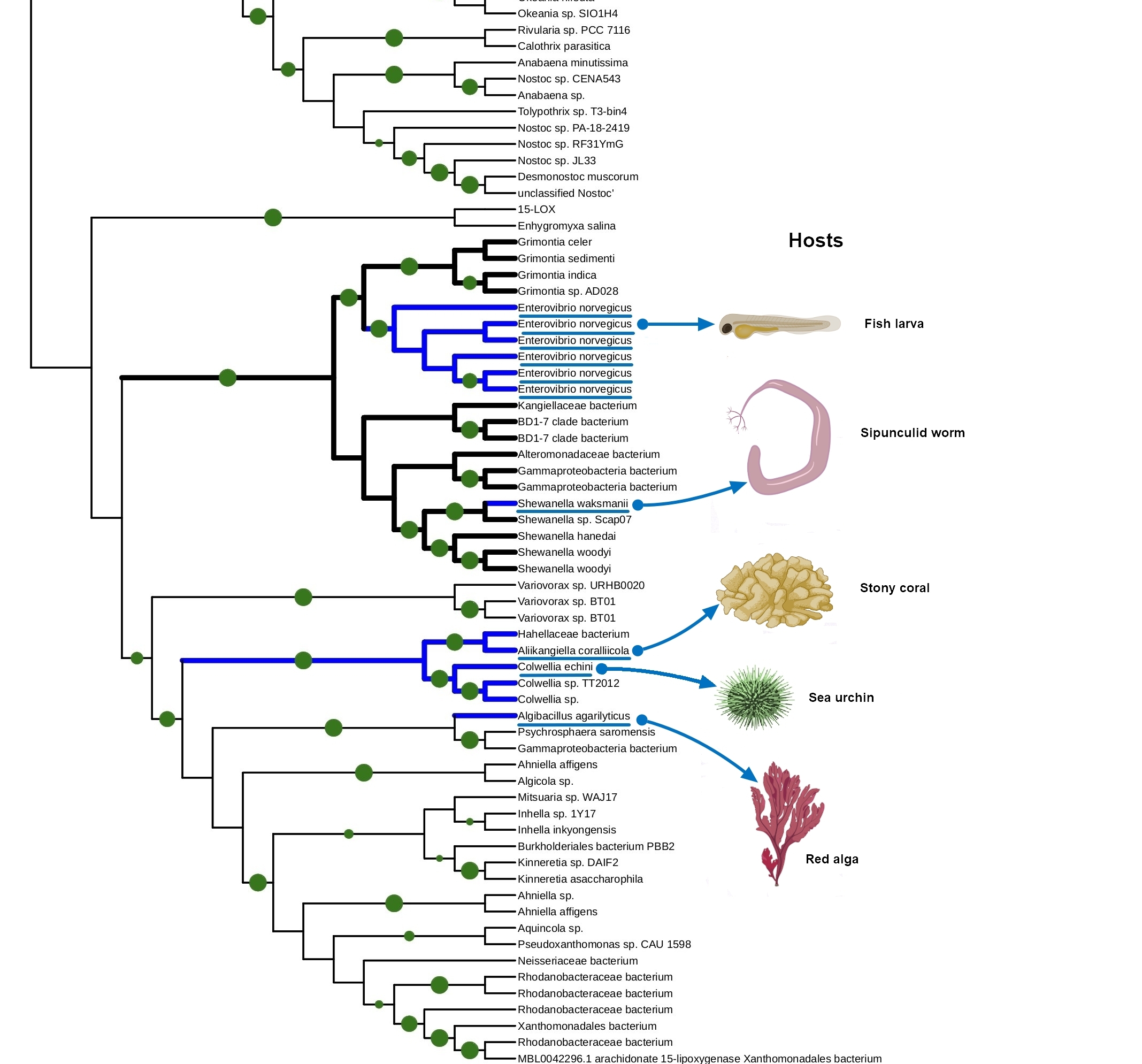

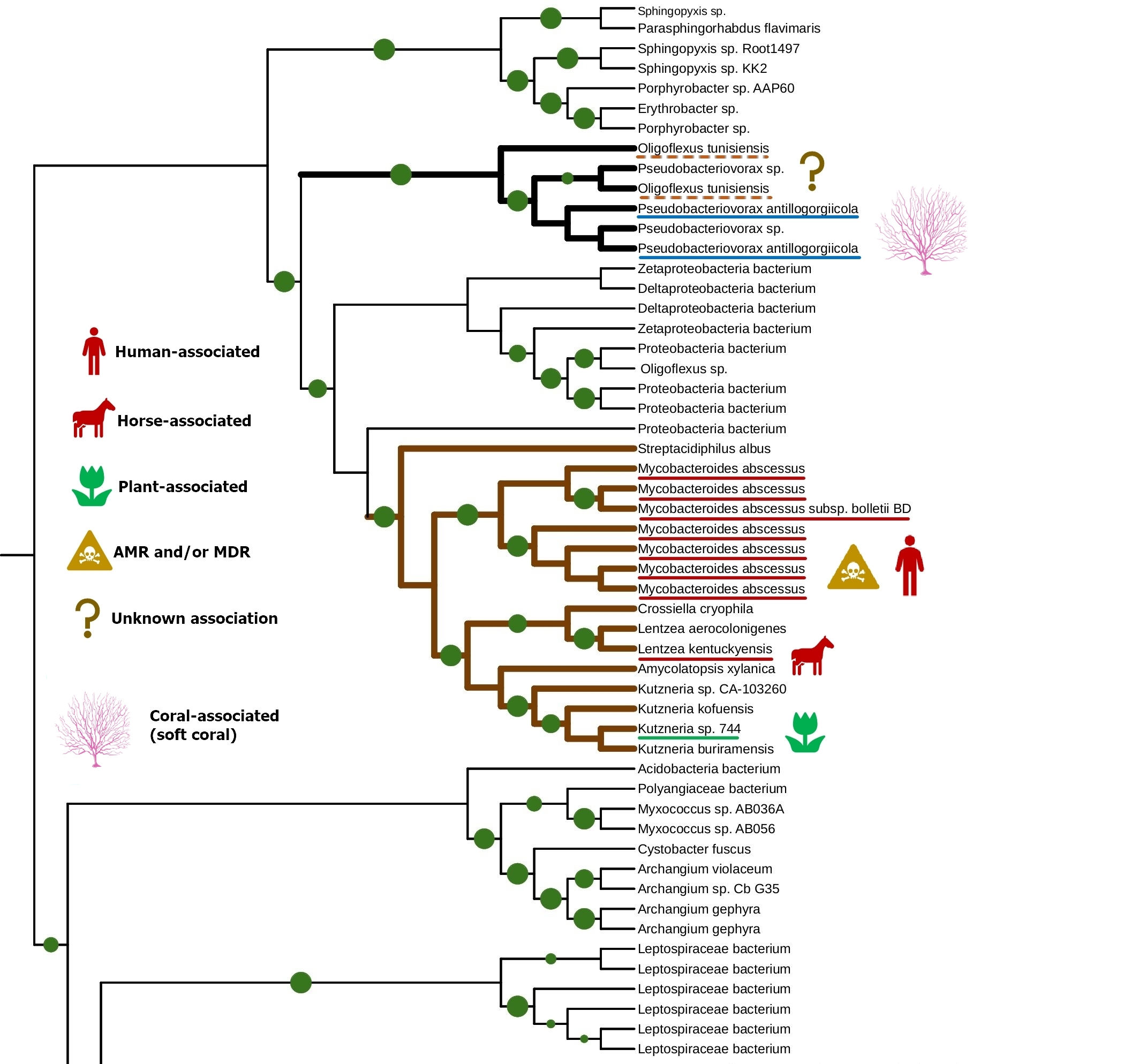

Trees and bottoms provide biochemical insights

The tight connection of plant colonization and animal pathogenicity is indirectly supported by the phylogenetic analysis of bacterial lipoxygenases. Phylogenetic trees of lipoxygenases associated with pathogenic or symbiotic bacteria did not follow the phylogeny of the bacteria themselves. For example, lipoxygenases of Nocardia spp. were closer to the lipoxygenase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa than the lipoxygenases of Kosakonia spp. (Fig. 3). If they were inherited from a common ancestor, it couldn’t be so — both Kosakonia and Pseudomonas are gammaproteobacteria, while Nocardia are actinomycetes. That's not the half of the story — another lipoxygenase-bearing gammaproteobacterium belonging to the Alteromonadales order, Colwellia echini (isolated from a sea urchin) shares another cluster with a vibrio, Enterovibrio norvegicus (Fig. 4). Only a group of other actinomycetes (Kutzneria — Mycobacteroides — Letnzea) are totally actinomycetal… if they were not clustered together with another Pseudomonadota bacterium, Pseudobacteriovorax antillogorgiicola, isolated from a coral (Fig. 5). It is evident that in all of these bacteria, lipoxygenases were not inherited from a common ancestor, but acquired by horizontal gene transfer.

This manual knowledge-based conclusion is reliable enough, if we consider only one protein family and know its history. However, some reviewers and colleagues were confused by the lack of any computational definition of HGT used in this work. I assume it is not quite needed here — such methods are generally used on whole genomes, when manual assessment of the phylogenies of shed loads of genes is the impossible task. This is not the case.

The dating of these HGT events also raised questions — I did not date them since it is not a good idea to use lipoxygenase as a molecular clock. Anyway, these HGT events are relatively ancient — they have surely occurred not in the course of a pair of years.

We suspected such rapid “superspreading” horizontal gene transfers in our previous paper [1], but after the update in the genomic databases, they appeared to be just an artifact of contamination with Pseudomonas aeruginosa sequences. So, I can now downgrade the alert, and I have indicated this in my preprint [3].

But if not the phylogeny of the bacteria themselves, then what? On the phylogenetic trees, lipoxygenases were clustered together not by phylotaxonomy, but by ecology. When I mapped the ecological functions of bacteria in the same colors as the categories of terms (human/vertebrate = red, plant = green, aquatic = blue), I found that “red” and “green” lipoxygenases were usually neighbours on the phylogenetic trees. And the “blue” lipoxygenases were located distantly. Like in our text analysis networks.

For me, it was clear evidence that the evolution of lipoxygenases — their horizontal transfers, their sequence changes — was driven by the host-microbe relationships of the respective bacteria. This means that lipoxygenases are involved in these relationships. Bacterial lipoxygenases play some role in the interactions with a host, but which exactly?

On a data visualization level, the correspondences between the similar patterns of green, red, and blue dots on the trees and networks may seem interesting. But some colleagues and reviewers are concerned that there is no mathematical and statistical proof of this connection. I don’t think this is even possible: each coloured dot means a type of host, which is ascribed to different objects in different models: to an ecophysiological term in the network or to a bacterial species on a phylogenetic tree.

I just avoided comparing these models directly by using evolutionary thinking:

-

- I constructed a common ecophysiological profile of the lipoxygenase-positive bacteria and found their common niches;

- The evolution of bacterial lipoxygenases followed the same ecological niches to fit them;

- OK, bacterial lipoxygenases are functionally related to these specific niches.

But even in this case, two types of computational models are linked by speculative consideration. This renders the paper a kind of hybrid between a review and an original study and gives a hypothetical nature to it.

But what if these correspondences reflect only a common environment? Maybe cross-kingdom host jumps and lipoxygenase gene transfer tend to occur within the aquatiс environment or within the terrestrial environment, but now between them due to a physical barrier? It could technically explain the both observed patterns… if not a small statistical thing in the structures of lipoxygenases analyzed.

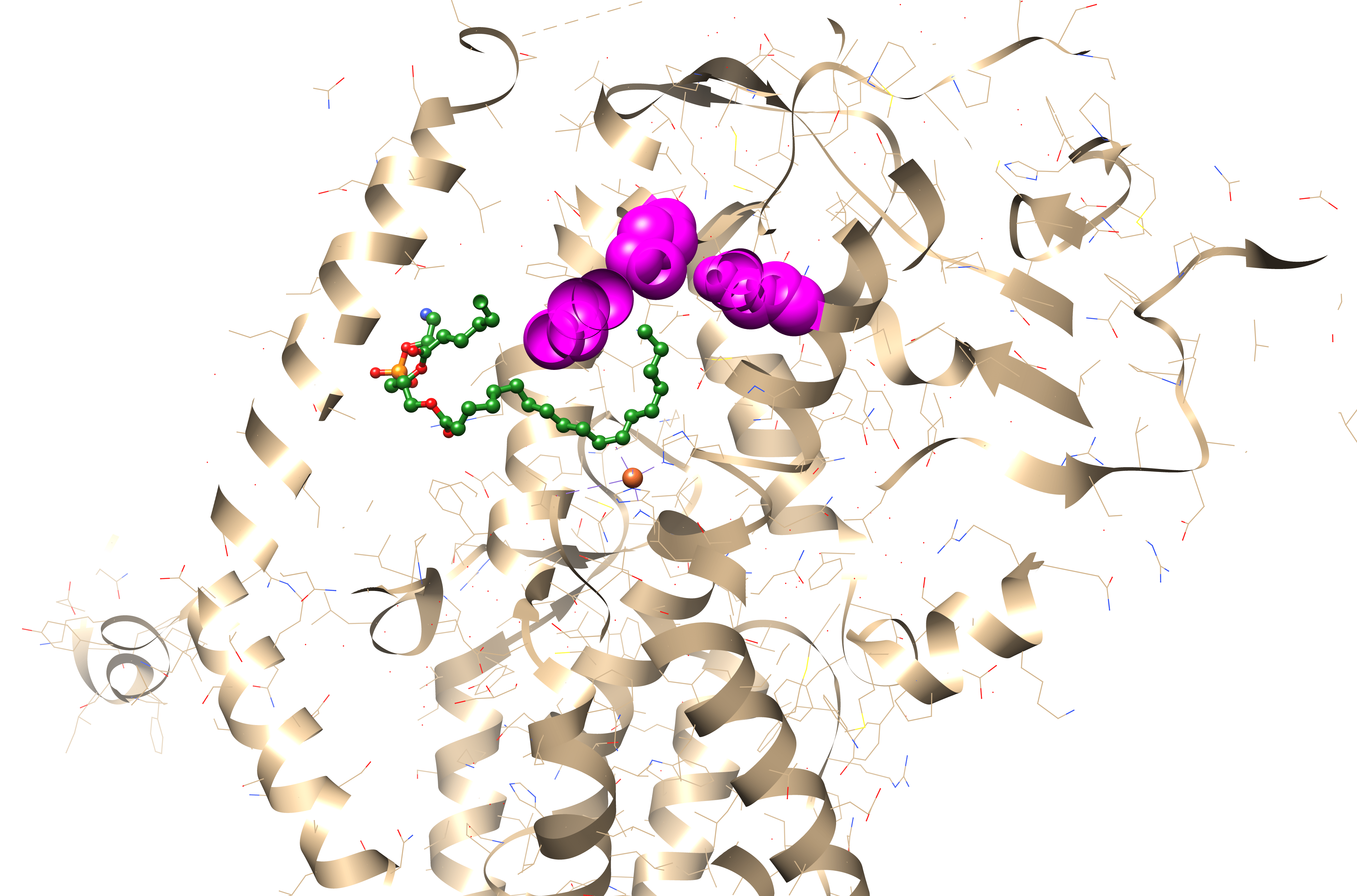

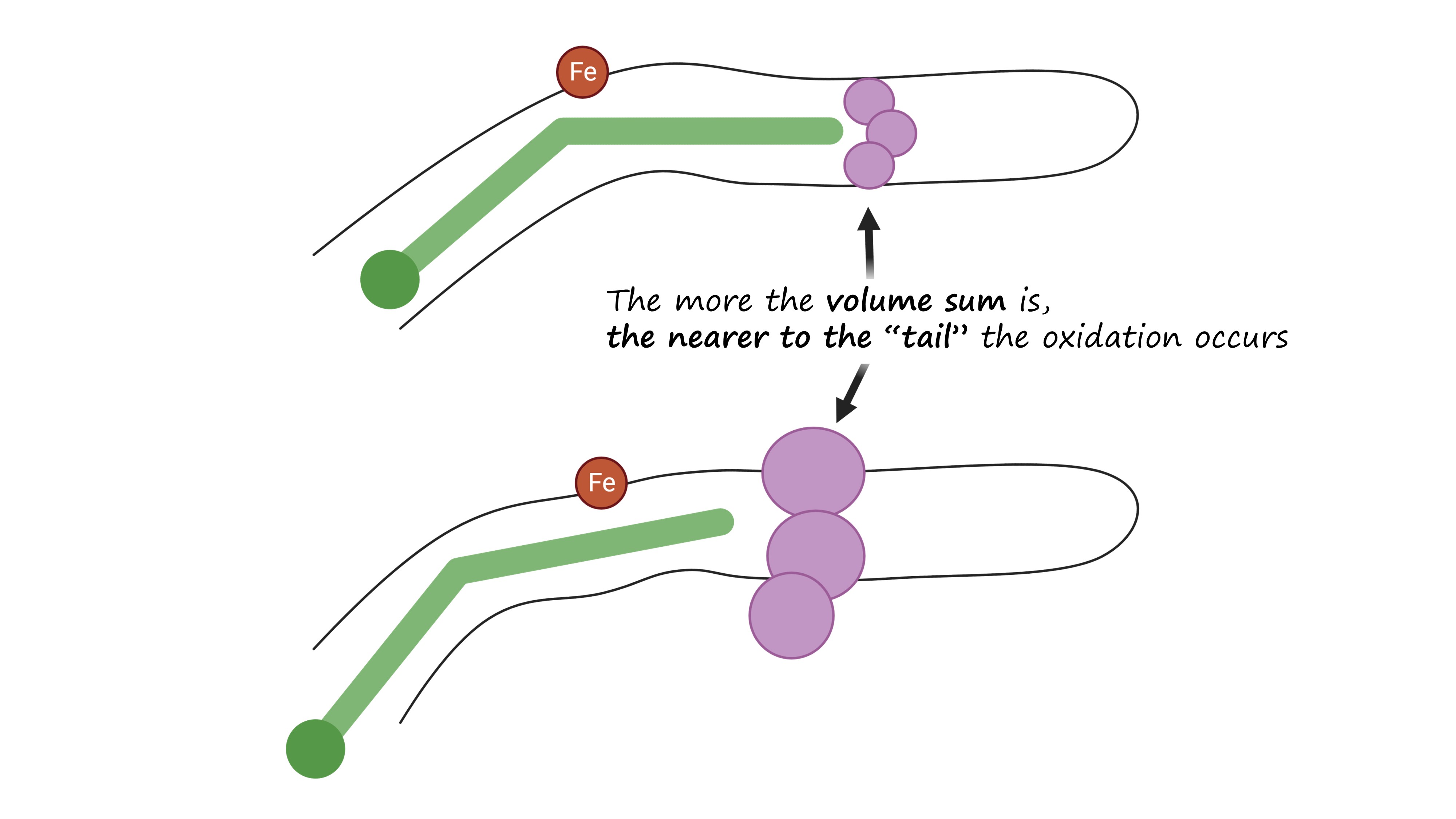

The regiospecificity of lipoxygenases is strictly determined by the bottom of the binding site. It consists of three amino acid residues: the less is their total molecular volume, the deeper the amino acid penetrates and the farther from its tail the oxidation occurs — because the catalytic iron ion which performs all the work is always in the sale place (Fig. 6, Fig. 7).

And the position of this “bottom triad” in the lipoxygenase sequences is very conserved. This means that we do not need the experimentally determined lipoxygenase structure to calculate it. We don't even need AlphaFold. All we need is to find this triad on the alignment, find the reference volume values for the respective amino acids and to sum them.

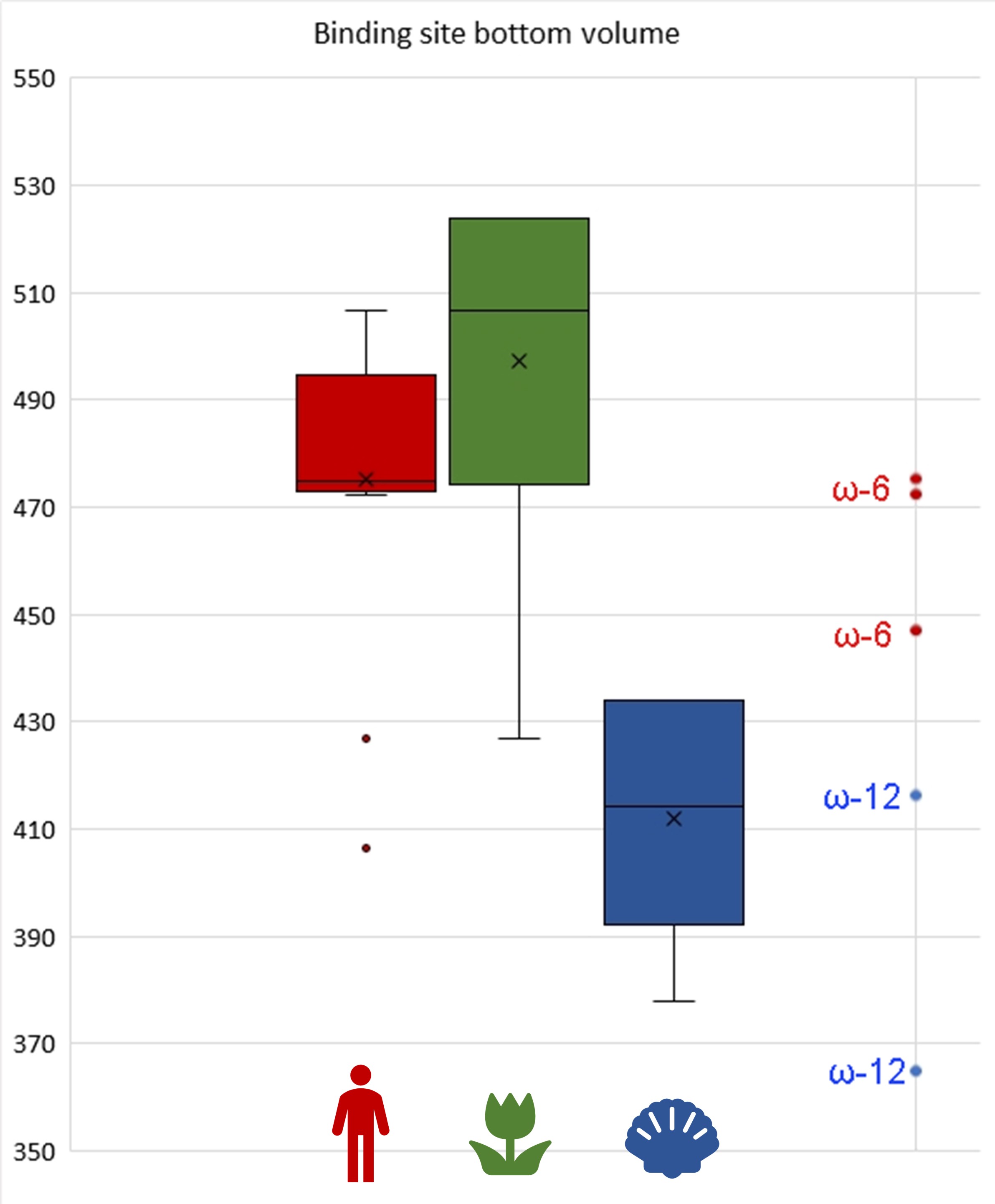

Such a statistical analysis of bacterial lipoxygenases showed a breath-taking association: the lipoxygenases of bacteria in both “plant-related” and “human-related” groups have similar bottom triad volumes corresponding to ω-6 lipoxygenases (this means the oxidation at the 6th position when counting from the tail). Meanwhile, lipoxygenases of the bacteria in the “aquatic” group had significantly smaller bottom — which shifts them towards the area of ω-12 lipoxygenases (Fig. 8). This means that they have quite different binding sites and activity and oxidize the fatty acids nearer to their “head”. On the scale of this binding site metric, lipoxygenases of “human-related” and “plant-related” bacteria were splitted from the lipoxygenases of the “aquatic-related” bacteria — like on the phylogenetic trees and ecological term network.

I stated above that “aquatic-related” lipoxygenases were separated from the “plant-related” and “human-related” ones in our phylogenetic trees. This means that almost none of ancient horizontal gene transfer events occurred between bacteria colonizing aquatic organisms, and bacteria colonizing terrestrial organisms. Almost none, but one.

A group of actinobacteria colonizing plants, vertebrates, and humans shared the same series of ancient lipoxygenase gene transfers with Pseudobacteriovorax antillogorgiicola, a bacterium isolated from a coral (Fig. 5). These actinobacteria had unusually small binding site bottoms compared to their counterparts in the “plant-related” and the “vertebrate-related” groups: their bottom sizes were present at the box plot as outliers… fitting in the range of “aquatic-related” lipoxygenase. This is the only branch of plant/vertebrate colonizers' lipoxygenases that once "jumped" into a coral colonizer (or vice versa?) — and this is the only set of plant/vertebrate colonizers' lipoxygenases which have the binding site metrics at the level of lipoxygenases of acquatic-associated bacteria.

This coincidence makes me me doubt that the extreme rareness of host jumps or lipoxygenase gene transfers between the plant-vertebrate colonizers and aquatic organism colonizers could be explained only by a physical barrier between the water and terrestrial environments. The binding site metrics show that the real barrier is of a biochemical, not by a simple physical, nature. And these unusual lipoxygenases, in the frameworks of my hypothesis, could be the unique lipoxygenases that fits in plants, vertebrates, and corals. If other lipoxygenases seem to be a broad-spectrum key to a host, this type seems to be a masterkey.

This statistical analysis could be the final argument for the assumption that I have revealed not just a correlation, but a causation. It could show that the host associations of bacteria lipoxygenases might reside on an underlying biochemical peculiarities, and some biological conclusions can be drawn. But I had only a small sample (I could include only the sequences with reliable phylogenetics and multiple sequence alignments) and only one case of outliers corresponding to a phylogenetic cluster. This requires very careful and conservative interpretation. Our hypothesis still cannot be proven definitively, but there are too many coincidences and correspondences to be just dismissed.

Surprisingly, the small sample size was not the object of extensive criticism by reviewers (among the journals which have still provided a review on rejection, which was rather a rare case). Maybe, this was caused by the fact that our hypothesis formally passed the Mann-Whitney test. In contrast, one of the reviewer claimed that a corpus size of 130 abstracts was too small for cooccurrence analysis. Mathematical grounds for such a claim remained obscure to me. Anyway, the linguistic analysis is not a bottleneck of the research in the terms of the sample size. The binding site statistics should be the central point of the discussion, but I have not seen this in any of the reviews. In any of two reviews. (See below).

How does this work? A biochemical hypothesis

The above statistical analysis provides some valuable clues into the mechanism of cross-kingdom host jumps between plants and animals. I have found that lipoxygenases of bacteria affecting plants and of their counterparts affecting humans/vertebrates generally have the binding site metrics characteristic for ω-6 lipoxygenases. Probably they have ω-6 activity, in contrast to lipoxygenases associated with affecting marine organisms, such as corals. This leads to an assumption that ω-6 activity of lipoxygenase predisposes its bacterial carrier to colonize plants and humans or vertebrates.

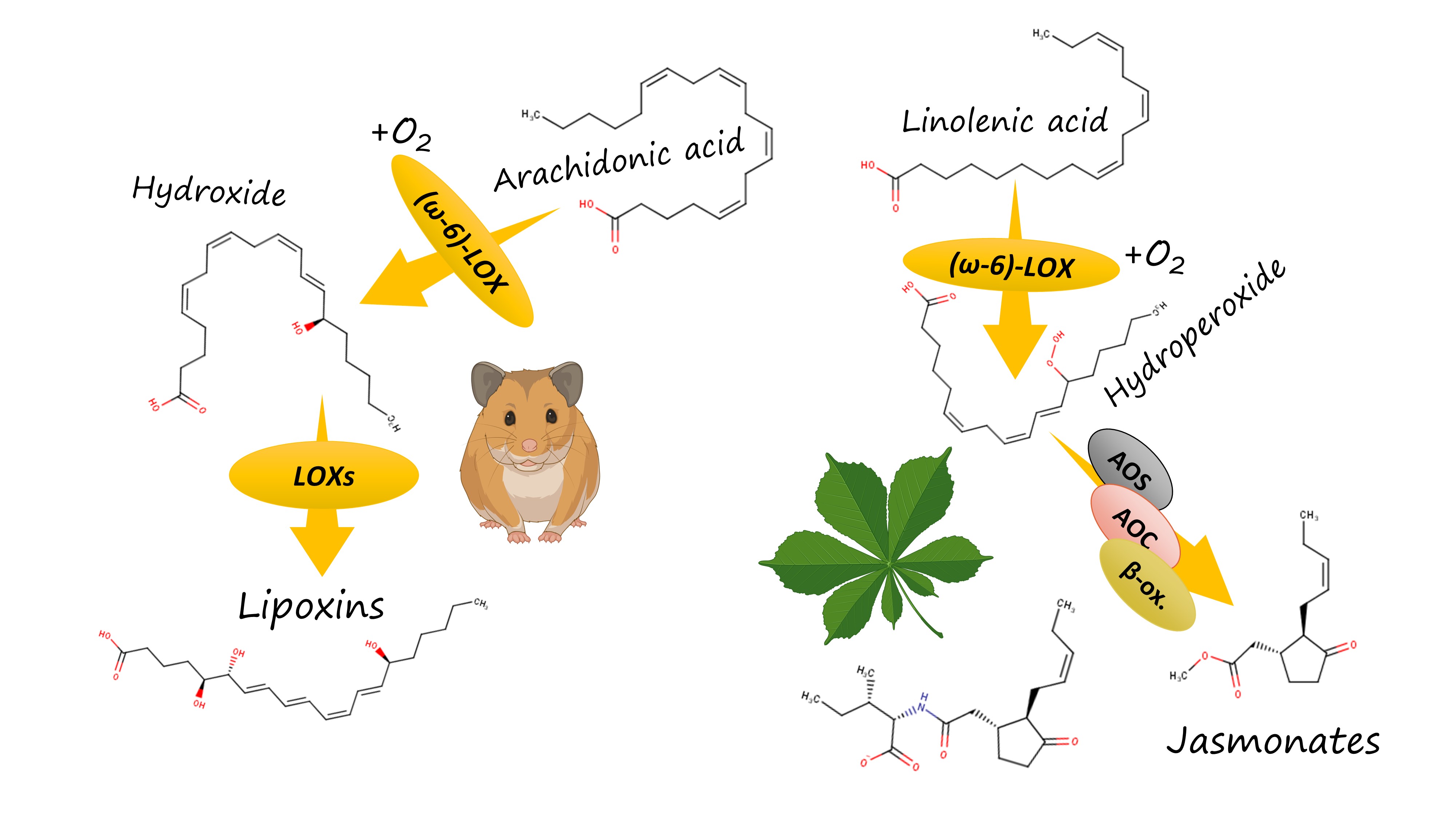

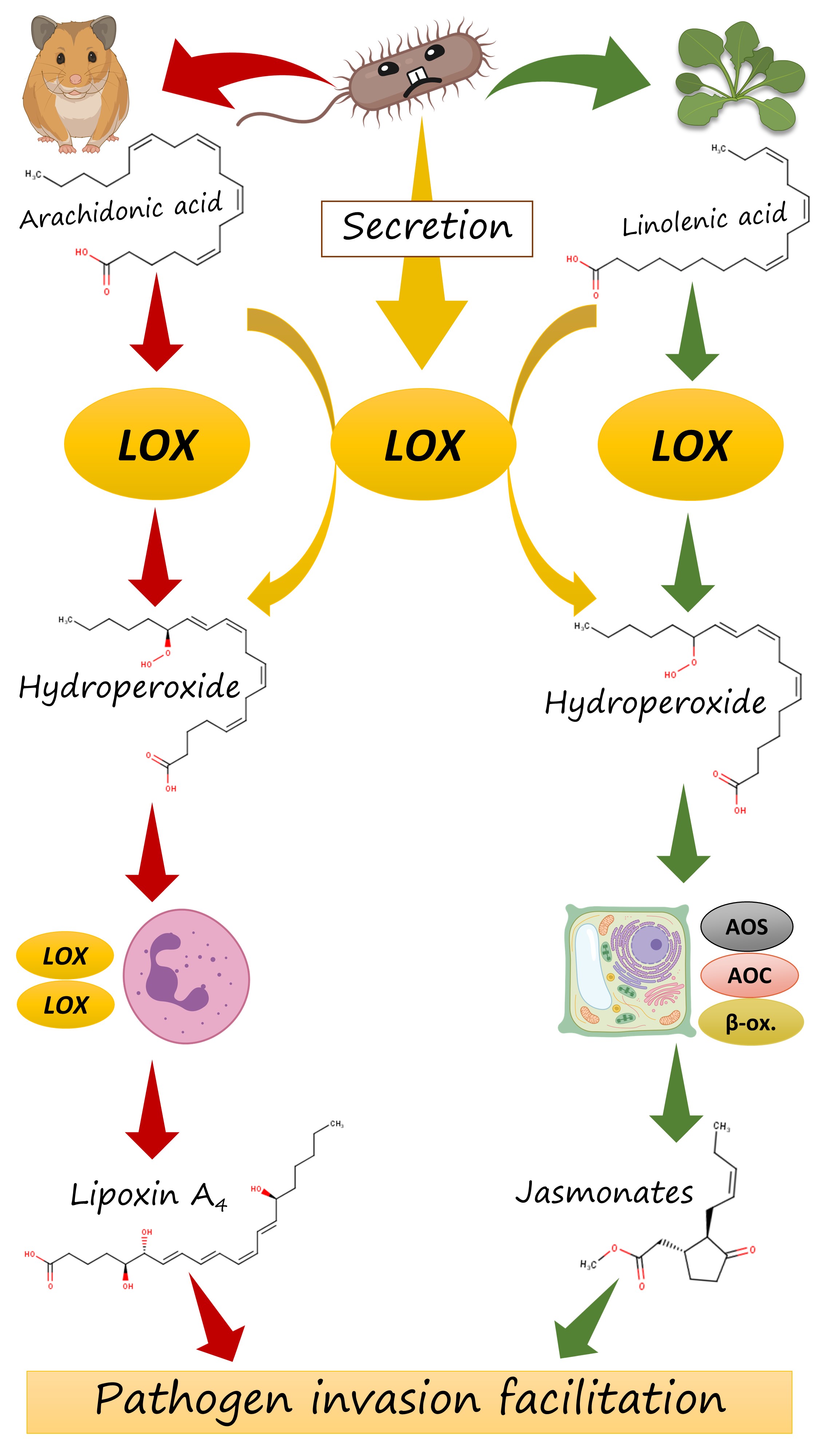

How does this work? Both plants and vertebrates, including humans, have an elaborate system of oxylipin biosynthesis and signalling. In vertebrates, lipoxygenase isoforms start a complicated and branched biosynthetic pathway of eicosanoid biosynthesis. It results in the emergence of a variety of pro-inflammatory oxylipins (such as leukotrienes) and anti-inflammatory mediators (such as lipoxins). The formation of leukotrienes requires that the oxidation starts with the 5-lipoxygenase introducing a hydroxyl group near the carboxylate "head" of a PUFA. In contrast, lipoxins and other anti-inflammmatory mediators are generally formed from compounds arising in the result of the action of a human ω-6 lipoxygenase (15-LOX).

In humans, this effect is exploited by the most infamous pathogen of our list, Pseudomonas aeruginosa [6]. Literature data (cited in my preprint) show that its ω-6 lipoxygenase oxidizes the extra quantities of host's polyunsaturated fatty acids and thus drives their entering into the pathway of anti-inflammatory oxylipin synthesis. For instance, the resulting w-6 hydroxides are further oxidized by the other lipoxygenase isoforms in the leukocytes and converted to lipoxin A4, an oxylipin which effectively suppresses inflammation. Deprived of the protective effect of inflammation, the host becomes naked to injury caused by this pathogen.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa has a well-characterized lipoxygenase whose binding site bottom volume is almost equal to the mean of my statistics. It shows the broad host specificity from plants to humans, so the experimental data for it can be extrapolated to other bacteria using my research.

But how does it act in plants? Plants have their own ω-6 lipoxygenase that starts the biosynthesis of jasmonates (Fig. 9). These oxylipins are potent plant hormones and are involved in a wide variety of defense responses. But — surprisingly — their overproduction can lead to the facilitation of a pathogen invasion. The matter is that jasmonates form an antagonistic crosstalk with the second group of plant defense hormones, salicylates. Their overproduction can suppress the induction of necessary defense responses by salicylates — and the plant becomes naked to an invasion.

This backdoor is exploited by a variety of bacteria and fungi, the most famous of whom is Pseudomonas syringae. It produces the potent chemical mimic of jasmonates, coronatine, which causes exaggerated jasmonate-driven response and undermined the plant's immunity.

I hypothesized that, when a bacterium from our list invades a plant, it could employ a similar mechanism and could just oxidize the plant's fatty acids with its ω-6 lipoxygenase. Its action of linolenic acid, on of the main PUFAs of plants, will lead to exaggerated synthesis of jasmonate precursors which are, in turn, converted to jasmonates. This amplifies jasmonate signalling in a pathologic manner line in the case of coronatine, and the salycilate-driven defense is weakened (Fig. 10 right). Like in the case of leukotrienes and lipoxins, misbalancing of different branches of the host's immune signalling can render it more susceptible to a pathogen.

In my preprint, I cited a lot of papers on the pathologic role of jasmonate signalling and its role in the hijack of a plant's immune signalling by a pathogen. Unfortunately, one of the reviewers stated that jasmonates can exert only a protective function with no discussion of papers cited. They were probably ignorant of these works, despite their presence in the reference list. In my response, I pointed them out to the appropriate references (one of which even had a title "Jasmonate in plant defence: sentinel or double agent?" [7]). This had no effect: this reviewer refused to review this paper and claimed that my response is a "formal reply"). With the one positive review and one negative, this turned the scales towards a rejection decision.

Rhizosphere, corals, and cystic fibrosis: common traits in lipoxygenase-bearing bacteria

In the course of the research, I identified some common traits of lipoxygenase-bearing pathogens and symbionts (Fig. 11). They were listed by the terms with the largest weight in our text analysis and the terms that form the "hubs" of the networks, as well as by the manual mapping of the hosts on the phylogenetic trees. Despite the hypothetical nature of the paper, they could be important for the further research and epidemiological surveillance. So, lipoxygenase-bearing bacteria (if not multicellular) have some common traits:

- they are extremely prone to affect cystic fibrosis patients. I don't know why, but this is an interesting research direction;

- they are dangerous for immunocompromised people, not for healthy people — maybe due to the adaptive immunity which makes the oxylipin signalling hijack useless in a healthy human;

- they are usually nosocomial or opportunistic, maybe by the same reason;

- but if they still have invaded a human, they are potentially dangerous for lungs;

- in plants, they usually affect roots or are endophytic. Maybe the ability to suppress the host's immune response is crucial for endophytic growth;

- they can affect insects and a wide range of marine invertebrates: sea urchins, corals, worms et al.

- they often show antimicrobial resistance — including the presence of carbapenemases, even NDM-1. They also often have an "emerging" status. I assume this is the case of a "correlation, not causation" mentioned by the reviewers, but this does not diminish the extent of the problem.

What now?

My preprint has been submitted to 6 journals and 2 public peer review services (consecutively, the next submission after rejection). All of them rejected it, one journal rejected with an attempt of a major revision. But only two of them (1 journal and 1 portal) provided full-fledged peer reviews. The other 6 academic outlets, including one public review portal, rejected without any review, sometimes with brief editorial comments, e.g. “due to the largely descriptive nature of the paper”.

While writing this post, I tried to summarize the reviewers’ comments, but here my sample was really too small: for 8 submissions, I have only 2 decision letters with peer reviews. These letters were generally of good quality, but sometimes reviewers failed to find some technical or supplemental details in the preprint — despite the fact I did describe them in the preprint, although briefly. The most surprising case of this series was when a reviewer stated that the Supplementary Figures and Supplementary Tables mentioned in the “Data availability” statement are not provided. Actually, they are in the “Supplementary Material” section and have been there for all 5 versions. You could visit the preprint page and make sure.

The misunderstanding of some places by the reviewers urges me to analyze the reviews carefully and use additional comments from our colleagues which I have heard in private conversations and seminars. Using them gave me an opportunity to find the most controversial points of the preprint and discuss them above.

It is evident that despite the elaborate statistics and computations, this preprint would be valuable not as a full-fledged research article, but as a hypothesis paper. We offered it to a journal which focuses on hypothesis and discussion papers, but it rejected it on the presubmission enquiry dues to... its IMRAD structure which is characteristic for research articles. The other journal who publishes hypothesis papers provided mixed reviews (one with the criticism of the flaws in data analysis, one positive, and one from the reviewer that does not believe in the pathogenic role of jasmonates despite my references). The consequences are already familiar to you.

I could try an option of publishing in an open access journal (some of them have a lower acceptance threshold), but I have no funding for the APC. This narrows the list of journals available for me.

Given these facts, I decided that bioRxiv could be the best place for a hypothesis paper. After all, it is the best place for unconfirmed scientific results that need to be cited and discussed, but interpreted carefully. It also provides the convenient way to reuse some parts of the research in further papers due to its flexible Creative Commons license — and I am going to use this advantage soon! So, I decided to keep my paper available as a preprint.

The fact that my preprint has been already been cited in a review of another research group (totally independent from me) as a hypothesis [8] indirectly indicates that it can be interesting and important for other research groups working in this field. Moreover, the phylogenetic trees of this group indirectly confirmed our phylogenetic reconstructions. Our first paper has been also cited by the ESCORIAL study team, which shows the importance of updating our results, even by a preprint. Finally, I had a chance to include some results of the preprint in a new review written together with my colleagues [9] by citing it. This shows that this preprint should remain available, citable and open for discussions even if it has not been formally published.

Our preprint was cited in the paper of R. Chrisnasari et al. [8] before its submission to some journals. As the result, reviewers repeatedly asked us to cite this paper in our preprint. I consider this slightly feasible: this could lead to the temporal paradox in the citations, where the paper is cited by a work which also cited this paper! A kind of Groundhog Day...

Our hypothesis and its computation justifications could inspire our colleagues form "wet biology" to perform experiments to check our biochemical assumption about the role of oxylipins in cross-kingdom host jumps. I am open to discuss such an experiment, as well as I am open to the requests of primary data in more convenient interoperable formats than a PDF. Please write to my email georgykurakin@gmail.com with any such requests.

And the last, but not the least: the failure to formally publish this paper does not imply the impossibility of a community review. Feel free to write comments under the preprint and under this post, to post community reviews on the preprint's pages on PubPeer and on ResearchHub. I shared a controversial hypothesis with you — then do a demolition job!

Acknowledgements

For the invaluable discussions and ideas about this preprint, I acknowledge my colleagues:

- Anastasiya Kuznetsova (an independent data visualization expert, https://nastengraph.medium.com/);

- Livia Leoni (Roma Tre University, Associate Professor at the Department of Science);

- Artem Tishkov (I.P. Pavlov Saint Petersburg State Medical University, Head of Physics, Mathematics and Informatics Department);

- Mikhail Gelfand and Yulia Sarana (Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, Center of Molecular and Cellular Biology);

- Natalia Bykova, MD, internist.

References

- Kurakin, G.F., Samoukina, A.M. & Potapova, N.A. (2020) Bacterial and Protozoan Lipoxygenases Could be Involved in Cell-to-Cell Signaling and Immune Response Suppression. Biochemistry (Moscow), 85, 1048–1063. DOI: 10.1134/S0006297920090059

- Kurakin, G.F. (2022) Bacterial Oxylipins: a Key to Multicellularity and to Combating Antimicrobial Resistance? Priroda, (2), 26-32. DOI: 10.7868/S0032874X2202003X

- Kurakin, G. (2022). Bacterial lipoxygenases are associated with host-microbe interactions and may provide cross-kingdom host jumps. bioRxiv, 2022-06. DOI: 10.1101/2022.06.21.497025

- Bengfort, B., Bilbro, R., & Ojeda, T. (2018) Applied text analysis with Python: Enabling language-aware data products with machine learning. O'Reilly Media, Inc. ISBN: 9781491963043.

- Erickson, M. F., & Pessoa, D. M. A. (2022). Determining factors of flower coloration. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 36, e2021abb0299. DOI: 10.1590/0102-33062021abb0299

- Morello, E., Pérez-Berezo, T., Boisseau, C., Baranek, T., Guillon, A., Bréa, D., Lanotte, P., Carpena, X., Pietrancosta, N., Hervé, V., Ramphal, R., Cenac, N., and Si-Tahar, M. (2019) Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipoxygenase LoxA contributes to lung infection by altering the host immune lipid signaling, Front. Microbiol., 10, 1826. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01826

- Yan, C. and Xie, D. (2015) Jasmonate in plant defence: sentinel or double agent? Plant Biotechnol. J., 13, 1233–1240. DOI: 10.1111/pbi.12417

- Chrisnasari, R., Hennebelle, M., Vincken, J. P., van Berkel, W. J., & Ewing, T. A. (2022). Bacterial lipoxygenases: Biochemical characteristics, molecular structure and potential applications. Biotechnology Advances, 61, 108046. DOI: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2022.108046

- Amoah, A.-S., Pestov, N.B., Korneenko, T.V., Prokhorenko, I.A., Kurakin, G.F., & Barlev, N.A. (2024). Lipoxygenases at the Intersection of Infection and Carcinogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(7):3961. DOI: 10.3390/ijms25073961

UPD on 21.01.2025: information about the citations of my preprint added, additional details about the common traits of lipoxygenase-bearing bacteria added.

UPD on 07.05.2025: some minor corrections made.

UPD on 11.05.2025: some minor misprints corrected.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in