Cancers exhibit mechanical irregularities which have significant implications for tumor development and resistance to treatment. These mechanical irregularities are sensed by cells via mechanosensitive interactions and can be grouped into four distinct physical hallmarks: elevated solid stress, elevated interstitial fluid pressure, increased stiffness, and altered tissue microarchitecture.

Solid stress, which was first recognized in 1997 an in vitro model of cancer1, refers to the mechanical force exerted and transmitted by the solid components within a tumor. The increased solid stress in tumors bears critical consequences for cancer growth and responsiveness to therapeutic interventions. Solid stress causes inadequate oxygen supply and impeded drug distribution via the compression of blood and lymphatic vessels2-6, altered trafficking and infiltration of immune cells7, increased invasiveness of cancer cells8,9, activation of tumorigenic pathways10, and even neuronal damage11,12.

Researchers are exploring how targeting solid stress in conjunction with standard cancer treatments may affect clinical outcomes. Early preclinical studies have demonstrated that this approach can extend survival in experimental mouse models3,6,13-15, and promising outcomes are being observed in ongoing clinical trials16. Despite gaining insight into some of the detrimental effects of solid stress within tumors, the precise cellular responses and molecular pathways activated by solid stress remain incompletely understood. This limited understanding primarily arises from the lack of suitable tools to directly measure the solid stresses experienced by individual cancer cells in the complex microenvironment of live tumors.

Existing methods for quantifying solid stresses are limited to larger scales of tissue and lack the precision needed to measure the stresses experienced by individual cancer cells. Additionally, these methods are also invasive, usually conducted at specific endpoints, and do not offer the capability to monitor these stresses over time. Furthermore, these existing methods only provide two-dimensional and one-dimensional profiles of solid stresses, failing to provide the full three-dimensional distribution of solid stress as a tensor; this is important for describing how stresses vary spatially across tumor. Therefore, it important to develop a non-invasive method that can continuously monitor the solid stresses within tumors in real time, offering high precision across different scales, from the level of individual cells to larger tissue structures. Such a method would provide deeper insights into the sources and consequences of solid stresses in tumors.

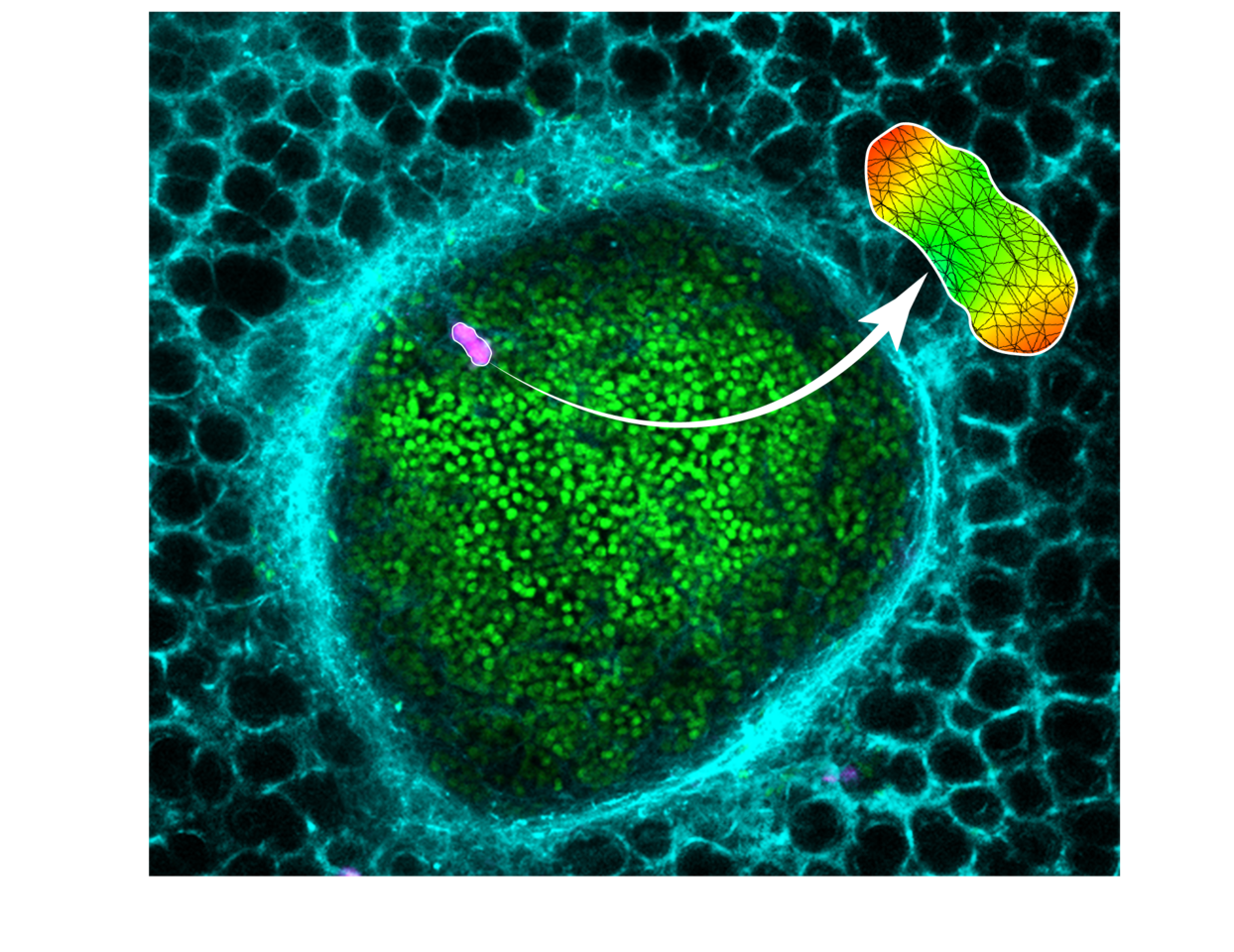

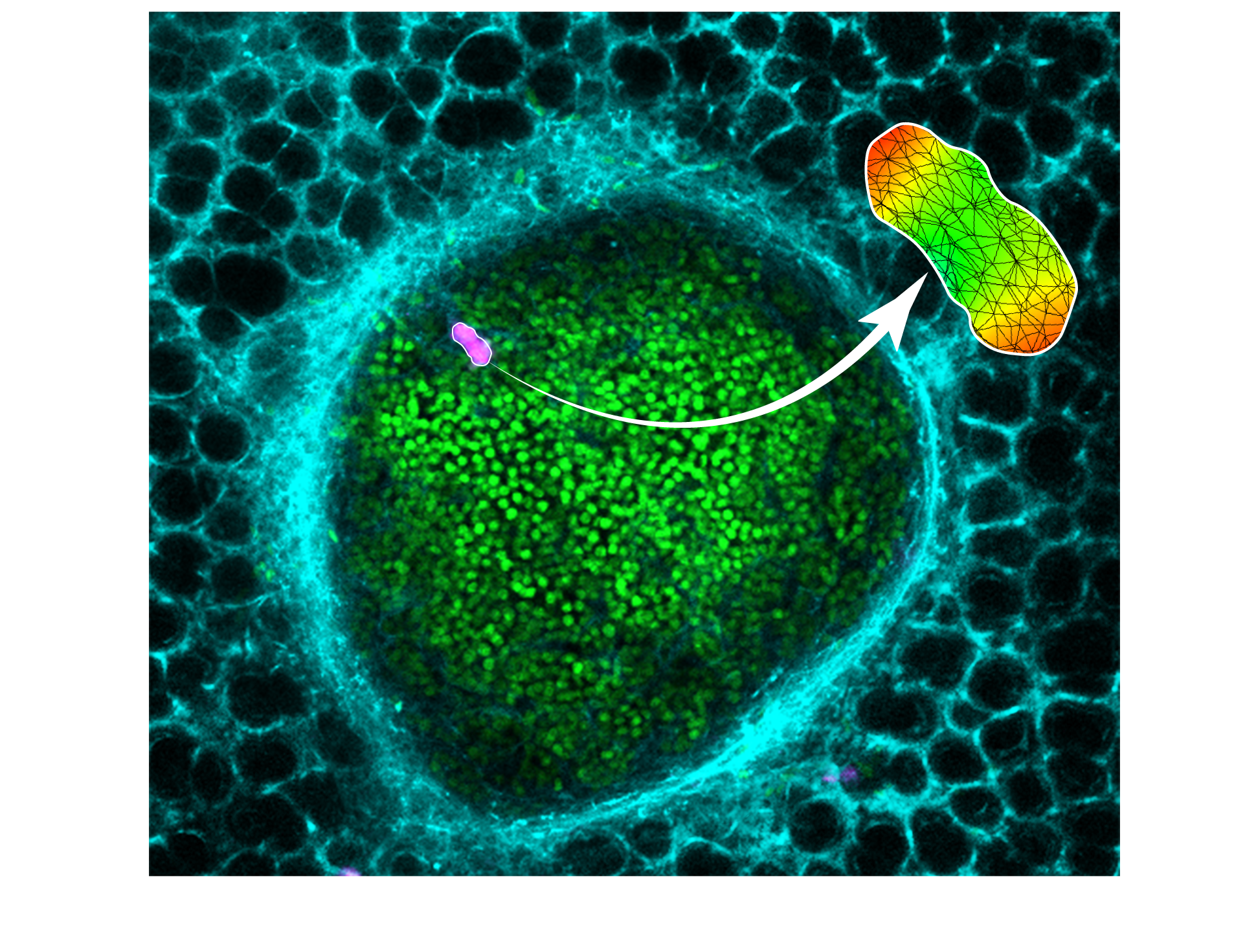

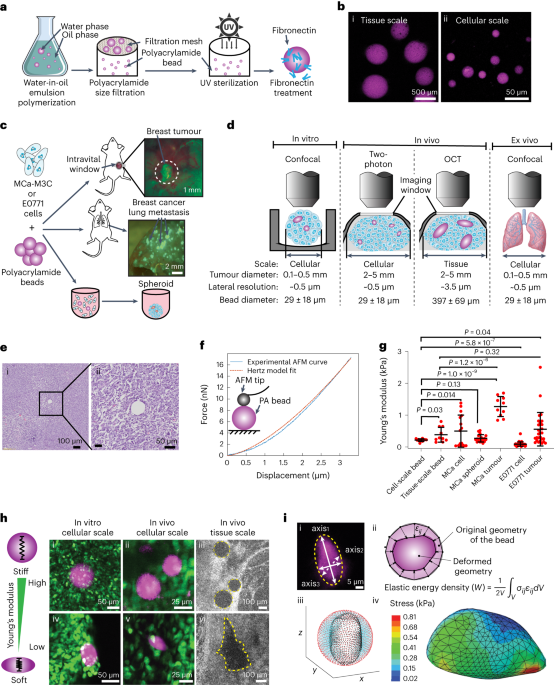

To this end, we have developed a method to monitor the solid stress in tumors non-invasively by imaging deformable hydrogel spheres which are embedded in live tumors. Our methodology uses intravital imaging and multi-modal imaging, giving us a window into the forces within the tumor. We are able to measure solid stress in three dimensions, both spatially and longitudinally, within live mice. Notably, we made an intriguing observation: the stress levels experienced by individual tumor cells are significantly lower, approximately five to eight times, than the stress levels measured at the tissue scale. This revelation carries significant implications, potentially shedding light on the mechanisms that enable cancer cells to withstand high mechanical stresses and offering a foundation for novel therapeutic strategies aimed at sensitizing cancer cells to mechanical stress-induced death. Additionally, our methodology shed light on the microenvironment-dependence of solid stress. Comparative analysis between solid stress levels in breast tumors and those in breast cancer lung metastases showed a marked increase in solid stress within metastatic contexts, although both primary and metastatic tumors originated from the same pool of cancer cells. Our findings underscore the influence of the tumor microenvironment in shaping solid stress generation, which may have implications for the disparate treatment responses observed between primary and metastatic cancer cases. Furthermore, our methodology allows monitoring of stresses experienced by single cells flowing through vessels, which allows researchers to study the forces that emerge during the early metastatic process and allows inquiry into the intravascular forces experienced by single cells used in therapies, such as CAR T and stem cells.

Our methodology enables measurement of solid stress in a metastatic lung tumor (individual cancer cells in green, lung capillaries in cyan) via deformable hydrogels (magenta). Mathematical modeling is used to quantify the solid stresses in the local region of the tumor.

Our innovative approach to measuring solid stress represents an achievement in noninvasive assessments of mechanical forces at the cellular level within living mouse tumors. We have yielded new insights into the influence of size scale and the microenvironment on solid stress. These findings have substantial implications for understanding cancer growth, progression, and treatment responses. Our methodology will allow researchers to make new connections between biochemical pathways and solid stress, and be an impactful tool in the emerging field of physical oncology.

References

- Helmlinger G, Netti PA, Lichtenbeld HC, Melder RJ, Jain RK. Solid stress inhibits the growth of multicellular tumor spheroids. Nat Biotechnol. Aug 1997;15(8):778-83. doi:10.1038/nbt0897-778

- Nia HT, Munn LL, Jain RK. Physical traits of cancer. Science. Oct 30 2020;370(6516)doi:10.1126/science.aaz0868

- Chauhan VP, Martin JD, Liu H, et al. Angiotensin inhibition enhances drug delivery and potentiates chemotherapy by decompressing tumour blood vessels. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2516. doi:10.1038/ncomms3516

- Padera TP, Stoll BR, Tooredman JB, Capen D, di Tomaso E, Jain RK. Cancer cells compress intratumour vessels. Nature. Feb 19 2004;427(6976):695. doi:10.1038/427695a

- Stylianopoulos T, Martin JD, Chauhan VP, et al. Causes, consequences, and remedies for growth-induced solid stress in murine and human tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Sep 18 2012;109(38):15101-8. doi:10.1073/pnas.1213353109

- Mpekris F, Panagi M, Voutouri C, et al. Normalizing the Microenvironment Overcomes Vessel Compression and Resistance to Nano-immunotherapy in Breast Cancer Lung Metastasis. Adv Sci (Weinh). Feb 2021;8(3):2001917. doi:10.1002/advs.202001917

- Jones D, Wang Z, Chen IX, et al. Solid stress impairs lymphocyte infiltration into lymph-node metastases. Nat Biomed Eng. Dec 2021;5(12):1426-1436. doi:10.1038/s41551-021-00766-1

- Tse JM, Cheng G, Tyrrell JA, et al. Mechanical compression drives cancer cells toward invasive phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Jan 17 2012;109(3):911-6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1118910109

- Das J, Maiti TK. Mechanical Stress-Induced Autophagy: A Key Player in Cancer Metastasis. Autophagy in tumor and tumor microenvironment. 2020:171-182:chap Chapter 8.

- Fernandez-Sanchez ME, Barbier S, Whitehead J, et al. Mechanical induction of the tumorigenic beta-catenin pathway by tumour growth pressure. Nature. Jul 2 2015;523(7558):92-5. doi:10.1038/nature14329

- Seano G, Nia HT, Emblem KE, et al. Solid stress in brain tumours causes neuronal loss and neurological dysfunction and can be reversed by lithium. Nat Biomed Eng. Mar 2019;3(3):230-245. doi:10.1038/s41551-018-0334-7

- Nia HT, Datta M, Seano G, et al. In vivo compression and imaging in mouse brain to measure the effects of solid stress. Nat Protoc. Aug 2020;15(8):2321-2340. doi:10.1038/s41596-020-0328-2

- Panagi M, Mpekris F, Chen P, et al. Polymeric micelles effectively reprogram the tumor microenvironment to potentiate nano-immunotherapy in mouse breast cancer models. Nat Commun. Nov 22 2022;13(1):7165. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34744-1

- Provenzano PP, Cuevas C, Chang AE, Goel VK, Von Hoff DD, Hingorani SR. Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. Mar 20 2012;21(3):418-29. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.007

- Zhao Y, Cao J, Melamed A, et al. Losartan treatment enhances chemotherapy efficacy and reduces ascites in ovarian cancer models by normalizing the tumor stroma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Feb 5 2019;116(6):2210-2219. doi:10.1073/pnas.1818357116

- Murphy JE, Wo JY, Ryan DP, et al. Total Neoadjuvant Therapy With FOLFIRINOX in Combination With Losartan Followed by Chemoradiotherapy for Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. Jul 1 2019;5(7):1020-1027. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0892

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Biomedical Engineering

This journal aspires to become the most prominent publishing venue in biomedical engineering by bringing together the most important advances in the discipline, enhancing their visibility, and providing overviews of the state of the art in each field.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Biosensing

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 26, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in