Positive rheotaxis, namely the ability to swim upstream, may not be a big deal for fish. But it is indeed surprising that single-cell microswimmers, without complex sensory organs, are able to do the same. For example, mammalian spermatozoa must travel through the reproductive tract to reach the egg, and E. coli can infect the upper part of the urinary tract.

The rheotaxis of these microswimmers turns out to be a purely physical phenomenon, resulting from an interplay of fluid shear, asymmetric body shape, rotating flagella, and the surface interaction. But which of these are essential? Can we further simply the system? In particular, is an asymmetric shape necessary? Locating the must-have’s is important in engineering, for example, when building drug-delivering microrobots that can swim against the blood stream.

Recent theoretical studies have predicted that the shape asymmetry is not necessary, spherical microswimmers may also exhibit rheotactic behavior. In our recent article, we provide experimental evidence for one such behavior: spherical microswimmers oscillate while swimming upstream inside quasi-two-dimensional microchannels. Our experiments agree quantitatively with theoretical predictions.

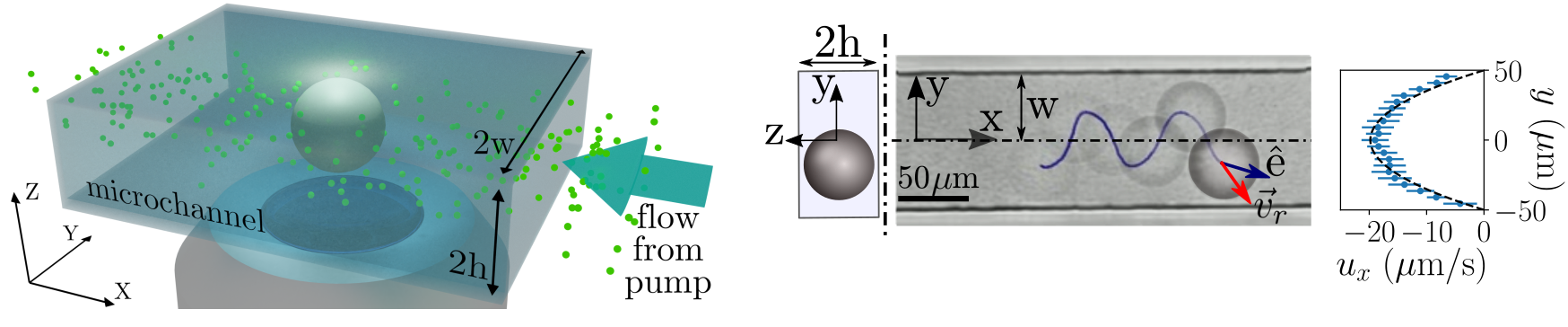

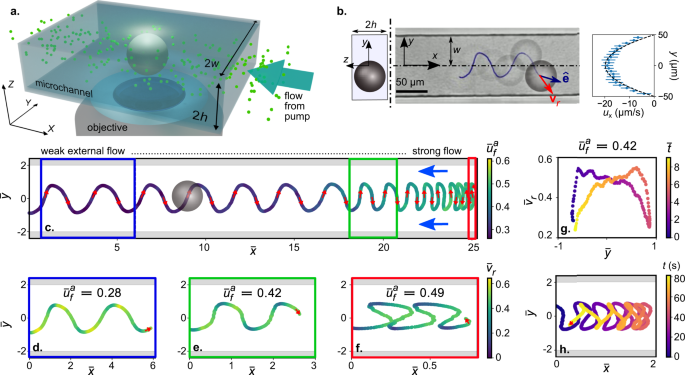

Our microswimmers are built from oil droplets in aqueous surfactant solutions. Surface tension ensures the spherical shape. Their locomotion is driven by a self-sustained Marangoni surface flow. Based on their hydrodynamics, these droplets are classified as weak “pusher squirmers”, characterized by their wall-following behavior. They also exhibit negative autochemotaxis, a tendency to recognize and avoid the chemical “trail” they left behind. We observed that inside microchannels, upon the introduction of a weak flow opposite to their swimming direction, these droplets stop following the walls but start to oscillate between the two walls while swimming upstream. As the flow speed increases, the droplets can be trapped oscillating without advancing, and eventually washed downstream.

The project started from a simple curiosity: How do the microswimmers react to being confined in a channel that is only slightly larger? Such a scenario is common in nature and engineering: bacteria often need to swim inside pores in the soil, while biomedical microrobots may need to go through narrow tubing or biological vessels. For our droplet microswimmers, such confinement may affect the dynamics in two ways: First, in Hele-Shaw cells (quasi two-dimensional), the flow field created by the droplet squirmer decays as r−3. We could hence expect that the walls of a narrow channel, acting as non-slippery boundaries, will change the flow profile around the droplet and hence its dynamics. Second, the channel will limit the diffusion of the repulsive trail, which may also affect the dynamics of our autochemotactic droplets. To test these ideas, Chenyu built a series of microfluidic chips with channels of different width and performed a few experiments. While the droplets follow one wall stably in a wide channel, they are observed to be oscillating between two walls if the channel is just wide enough to fit a few droplets.

Then Carola and Ranabir joined to seek better control of this oscillation. Looking back now, it was really a crucial moment when they noticed a small dust traveling through the channel, indicating a residue flow opposite to the swimming direction of the droplet. They soon found out that this background flow is a necessary condition for the oscillation: when the flow is absent, the droplets swim straight along the channel wall. Once an opposite flow is present, they start to oscillate regularly while swimming upstream. Ranabir further modeled the system using a finite-sized ideal squirmer with hydrodynamic interactions with the confining walls and the imposed shear flow. The model shows, already to the first order, quantitative agreement with the experimental results.

We still needed to investigate the effect of negative chemotaxis. Babak developed a technique that can mark the trails behind the droplets. Experiments showed that the trails overlap perfectly with the trajectories of the droplets, indicating that the autochemotaxis is not key to the oscillation.

We are hence certain that this is indeed the rheotaxis predicted by several theoretical studies: Inside a narrow channel, a spherical microswimmer may oscillate while swimming against the flow.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in