Midnight Mixing in the Arctic: How Meltwater Shapes Carbon Uptake

Published in Earth & Environment and Ecology & Evolution

When I began my PhD studying the impacts of freshwater runoff on marine carbon cycling, one of the first things I read stopped me in my tracks. Multiple studies had observed that glacial meltwater causes unusually low levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in coastal waters, enhancing the ocean’s uptake of carbon from the atmosphere. However, unlike other descriptors of the marine inorganic carbon system like dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and total alkalinity (TA), the partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) doesn’t behave in a “conservative” way during mixing. In other words, pCO2 concentrations don’t mix linearly, and the concentration of a mixture does not equal the sum of its parts.

It was fascinating and frustrating. The literature was clear that CO2 concentrations drop near glacial meltwater plumes. Yet, the explanations felt vague. At first I didn’t understand how or why pCO2 would behave nonlinearly, but I was curious to learn. I didn’t just want to read or think about this “nonconservative” behavior. I wanted to see it first hand, measure it, and understand why it happens.

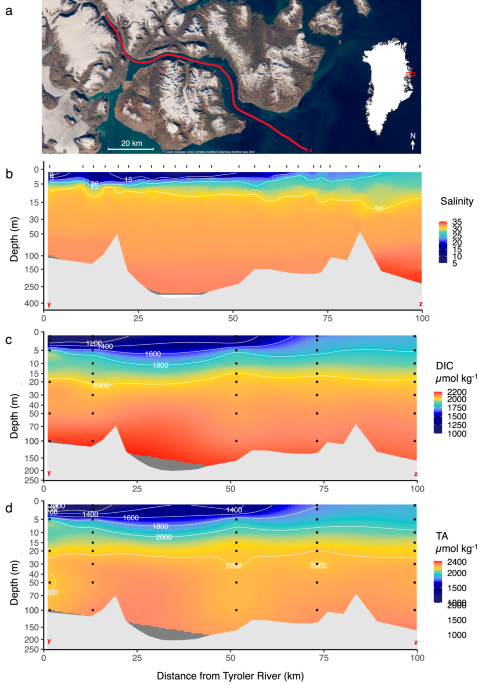

That’s how I found myself in Northeast Greenland, in the world’s largest national park, ready to run the first experiment of my PhD. The place itself is overwhelming: endless mountains spilling glaciers into mammoth fjords, muskox grazing on the sparse vegetation, and walrus hauled out on ice reminding you just how far from home you are. Very few people ever get to come here, and every moment felt like a privilege.

The heart of my experiment was deceptively simple: mix seawater and glacial meltwater in different proportions, measure what happens to pCO2, and compare it with how DIC and TA change. In practice, that meant long days of sampling along the fjord, followed by even longer nights, often well past midnight, replicating mixing experiments in the rusted shipping container that served as my lab. There’s something oddly meditative about circulating icy water through sensors in the small hours, with the Arctic summer twilight never fully fading.

And then, the revealing moment: the curve. As I plotted my data, pCO2 didn’t just drop linearly. It dipped dramatically at mid-salinities before rising again. A clear, U-shaped signal that I had only ever seen described in theory. Later, back home, I built models to work out why this occurs. It turns out that meltwater’s chemistry changes the “buffering capacity” of seawater. In other words, glacial meltwater is so pure it dilutes not just carbon but also the ions that help buffer seawater against acidification. Mixing freshwater and seawater changes the pH of the water parcel and therefore the relative proportions of carbonic acid, bicarbonate ion and carbonate ion that make up DIC. Hence, changes in CO2 concentrations and pCO2 are nonlinear.

Two years after that first experiment, the paper is finally out. By chance, I’m back in Greenland as it’s being published, standing once again by the same fjord where it all started. The Greenland ice sheet is still melting and the ocean is still quietly pulling CO2 from the atmosphere. But now, at least, I understand a little more about the why.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in