Since the discovery of the first fossil in the Neander Valley in 1856, our image of our Neanderthal relatives, along with the cognitive and intellectual capacities they possessed, has gone through many changes. Until the middle of the 20th century, Homo neanderthalensis was described as wild and primitive. New discoveries helped modify this view, but still Neanderthals were generally thought of as having no concept of symbolism, i.e., the investment of objects or activities with special meaning representing an idea shared by a group, eventually becoming a part of that group's identity.

Evidence that Neanderthals practised funerary rites and personal decoration suggest they were, in fact, not bereft of such capacity. The discovery of an accumulation of crania belonging to large herbivores in the Cueva Des-Cubierta (Pinilla del Valle, Madrid), however, has provided much more evidence in this regard. Indeed, it is the clearest yet of the specific use of a space by Neanderthals for symbolic activities involving hunted animals.

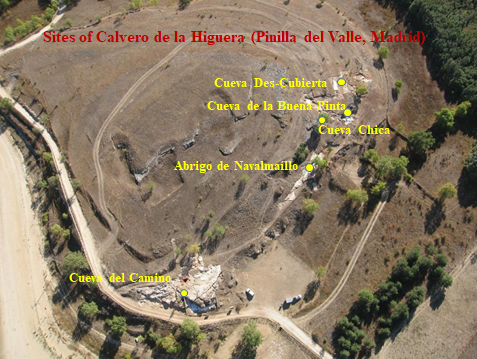

The site lies in the valley of the River Lozoya, an area of outstanding natural beauty on the southern face of the Sistema Central mountain range, less than 100 km from Madrid, the capital of Spain. While the discovery of a hunting sanctuary in this valley was indeed surprising, it is less surprising that it was found in this location: Neanderthals were present here for over 200,000 years. Today, the area has taken on the nickname of the Valley of the Neanderthals.

The valley is a karstic landscape with caves and rock shelters which in the past were occupied by Neanderthals and/or spotted hyaenas (Crocuta crocuta), the activities of both leaving large accumulations of remains.

In 2002 a project was begun, which now is led by Professor of Palaeontology Juan Luis Arsuaga, Professor of Geology Alfredo Pérez-González, and myself - an archaeologist, Director of the Museo Arqueológico y Paleontológico de la Comunidad de Madrid [the Archaeological and Palaeontological Museum of the Madrid Region], and Co-director of the Instituto de Evolución en África [The Institute of Evolution in Africa] to review a site excavated in the 1980s, interpreted as a hyaena den. In that same year we began to discover evidence of Neanderthal and/or hyaena activity in most of the caves in the valley. Certainly, the five basic needs of any Neanderthal would have been met here: drinkable water, food and clothing (from both vegetable and animal material), cavities for shelter, raw materials for making stone tools, and dry wood for making fires in hearths. Clear evidence for this has been found in the occupation of the Navalmaíllo Rock Shelter, an 'abri' or bluff shelter in the limestone rock, under which Neanderthals established camp on numerous occasions between 40,000 and 80,000 years ago. The tools they left behind, all of which belong to the Mousterian technocomplex, leave no doubt.

Although the ceiling of the shelter collapsed over the sediment containing these archaeological remains, it has been possible to recover the remains of hearths around which the occupants undertook their activities, along with bones of the animals they consumed, and pieces of ochre used for personal decoration.

Illustration recreating the Abrigo de Navalmaíllo where Neanderthals had their campsite. © Y. González and E. Baquedano.

In 2009, while investigating the provenance of Middle Pleistocene micromammal remains, we discovered a cave, less than 100 meters from the Navalmaíllo Rock Shelter, we named the Cueva Des-Cubierta (a pun on the Spanish words for 'uncovered' [the ceiling had been eroded away] and 'discovered'). The cave shows levels with the presence of hyaenas and humans during the Mid-Pleistocene. Surprisingly, we also found an Upper Pleistocene level in the main gallery (Level 3) with no signs of carnivore activity but which contained 35 crania belonging to large herbivores, all of which were members of horned (bison, aurochs, rhinoceros) or antlered (red deer) species. The chronology of the level, the stone tools it contained, and the fossilised remains of a Neanderthal child, all pointed to the Mid-Palaeolithic and Neanderthals around 40,000 years ago. However, unlike the Navalmaillo Rock Shelter, they did not live in this cave.

Excavation at the Cueva Des-Cubierta. © Javier Trueba.

Neanderthals brought the heads of animals to the cave intentionally, partially processed them outside, and placed some over small hearths inside. The presence of rubefacted sediment and stones, charcoal and burnt bones, clearly indicates the existence of structures made for combustion, and their link with the crania.

These large, horned skulls were transported to the cave in recurrent fashion, perhaps as hunting trophies, thus representing courage, intelligence or hunting skill, and perhaps justifying leadership and reflecting an incipient hierarchy. We believe this is the most parsimonious interpretation. Alternatively, their presence might be related, as in some modern hunter-gatherer societies, to sympathetic or propitiatory magic, or rites of initiation and passage. These activities may have been accompanied by dancing, music (percussion) and singing. But since sounds, movements and thoughts do not fossilise, we may never know!

%20javier%20trueba.png)

Enrique Baquedano and some of the Des-Cubierta crania found. © Javier Trueba

The Cueva Des-Cubierta is truly exceptional. It demands that we look at Neanderthals in a new light, and that we re-examine ourselves. Our species has long believed itself the only one to have a concept of symbolism, but it now seems we are obliged to share this intellectual space - and the evolutionary pedestal upon which we have placed ourselves - with our extinct relatives the Neanderthals. Indeed, it appears they were more sapiens than we ever thought.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Human Behaviour

Drawing from a broad spectrum of social, biological, health, and physical science disciplines, this journal publishes research of outstanding significance into any aspect of individual or collective human behaviour.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in