Network topology controls the fate of cells during development and disease

Published in Cancer, Protocols & Methods, and Cell & Molecular Biology

In this article, we explored the mechanisms underlying how cells make decisions about their future states—a process fundamental to development, tissue regeneration, and disease progression. These decisions, termed “cell fate transitions,” are governed by complex genetic networks involving interconnected feedback loops. Our study investigates the design principles of these networks and how their structures influence cellular outcomes.

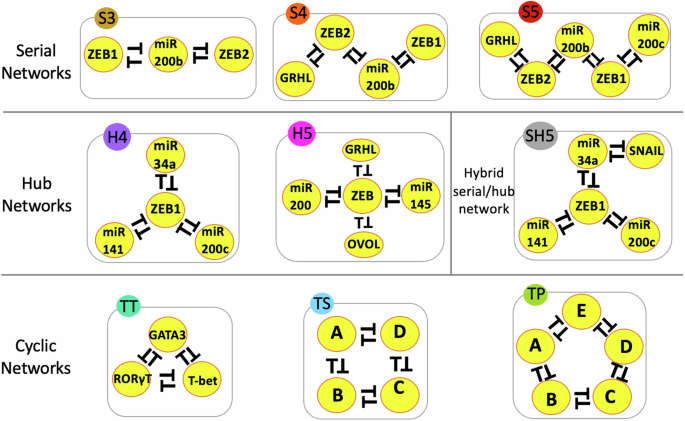

Cell fate transitions are driven by genetic circuits comprising feedback loops, which can be thought of as interconnected switches. These loops influence whether a cell remains in its current state or transitions to another. By studying these networks, we aimed to understand how the structure of the network affects its behavior. Specifically, we identified three key network topologies: serial (chain-like), hub (where multiple switches connect to a central node), and cyclic (looped connections).

Our findings revealed that network topology plays a crucial role in determining the range of possible stable states—or “decisions”—a cell can make. Serial networks, where feedback loops are connected end-to-end, allow for a greater diversity of stable states. This diversity increases as the network size grows, enabling cells to access multiple potential fates. In contrast, hub networks tend to restrict the range of stable states, promoting fewer outcomes, such as binary decisions. Cyclic networks, which feature interconnected loops in a circular arrangement, behave similarly to serial networks in fostering higher-order stability, often allowing more complex decision-making.

Another important discovery was the role of self-activating nodes in these networks. Self-activating nodes, which can turn themselves on, tend to increase the number of stable states. This feature introduces greater flexibility to the network but also reduces the dominance of topology in controlling outcomes. This property could explain how certain cellular processes, such as the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cancer, enable cells to adopt hybrid or intermediate states that enhance their ability to migrate and invade other tissues.

To deepen our understanding, we modeled several biologically inspired and synthetic networks, including ones derived from cancer metastasis and immune cell differentiation. We observed that even networks with the same number of components behaved differently depending on their topology. For example, serial and cyclic networks with similar compositions allowed for greater phenotypic diversity compared to hub-like configurations.

Our study also explored strategies to manipulate these networks to influence cellular behavior. By systematically perturbing network edges—either by removing interactions (edge deletion) or reversing their effects (edge sign reversal)—we demonstrated how network stability could be shifted toward fewer or more stable states. This approach could have significant implications for controlling cellular plasticity in developmental biology and diseases such as cancer. Specifically, targeting self-activating nodes or modifying feedback loops may provide new opportunities to restrict harmful cell behaviors, such as those observed during cancer metastasis.

These findings highlight the intricate relationship between network structure and cellular decision-making. By identifying the design principles governing these processes, we aim to provide insights that could advance therapeutic strategies, from guiding stem cell differentiation to mitigating tumor heterogeneity. Our results underscore the need for further exploration of these principles, particularly in larger, more complex networks and under stochastic conditions. Such efforts could pave the way for engineering robust synthetic networks to control cell fate transitions with precision.

Follow the Topic

-

npj Systems Biology and Applications

An online Open Access journal dedicated to publishing the premier research that takes a systems-oriented approach and encourages studies that integrate, or aid the integration of, data, analyses and insight from molecules to organisms and broader systems.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Next-Generation Mammalian Cell Bioprocessing: Systems Biology, Synthetic Biology, and Beyond

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 15, 2026

Systems mechanobiology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 28, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in