Nonequilibrium lattice dynamics: A new paradigm for modeling cooperative signaling in a large protein complex

Published in Chemistry, Physics, and Cell & Molecular Biology

How do bacteria navigate in complex environments? This simple question has been studied for decades in the model bacteria Escherichia coli to reveal general principles of cellular information processing. Nevertheless, recent experiments and theory are beginning to show a new paradigm that highlights the importance of nonequilibrium cooperative interactions in signaling.

E. coli perform chemotaxis: by sensing their environment they can move up or down gradients in chemical concentrations to, for example, look for areas rich in sugars necessary to grow and reproduce. This behavior is achieved with a simple biochemical network: first, receptors on the cell surface bind to chemical attractants; this measurement is then propagated to activate messenger proteins within the cell, which in turn control the flagella, the motors that propel the bacteria forward or change its heading direction.

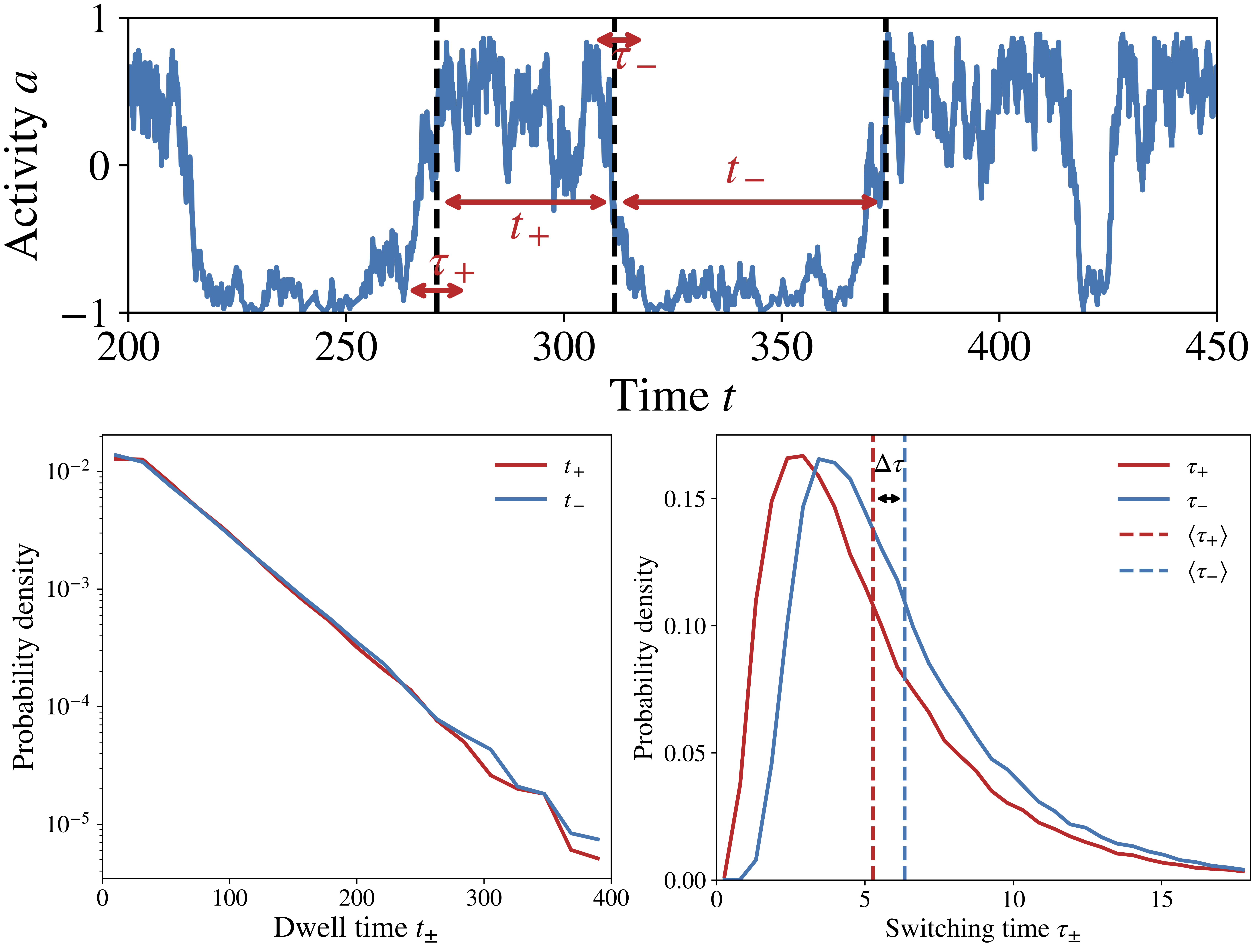

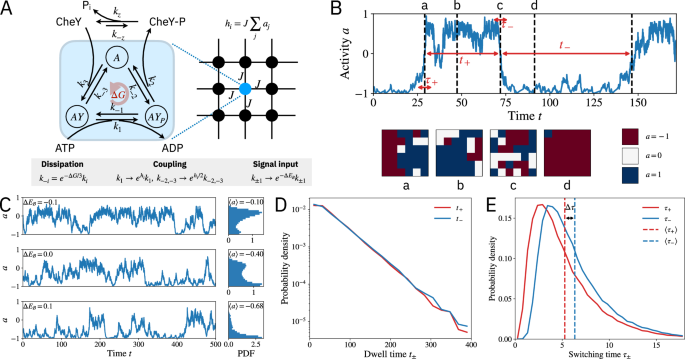

Figure 1: The activity switching trajectories in the chemosensory array (top) break time-reversal symmetry on a statistical level: the forward versus backward switching times follow different distributions (bottom).

The nonequilibrium lattice model: Understanding the switching time asymmetry and its implications for signaling function requires two essential ingredients: cooperativity and dissipation. Cooperativity stems from coupling between many chemoreceptors, which form a spatially extended lattice on the cell membrane. Dissipation comes from continuous hydrolysis of ATP by a kinase protein that propagates the signal from the receptors to intracellular signal carriers via phosphorylation reactions. By introducing a nonequilibrium lattice model of the that, for the first time, incorporates these two mechanisms, our paper explains the switching asymmetry and elucidates how signaling response is enhanced by the interplay between dissipative chemical reaction cycles and the collective behavior of the receptor lattice.

Key insights on cooperative sensing: Our investigations reveal two key insights into the function of the chemosensory array.

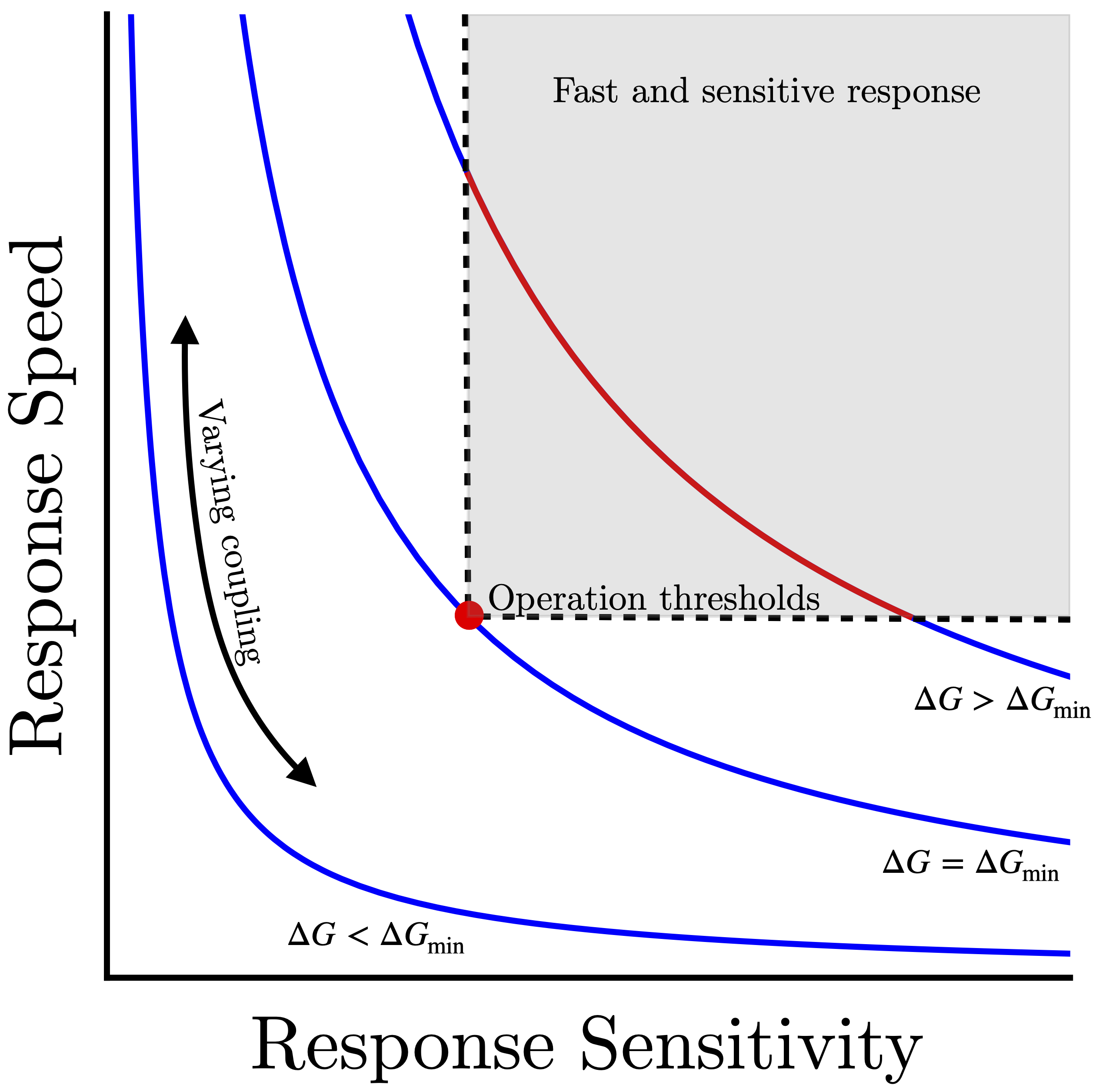

2) Dissipation eases the speed-sensitivity trade-off: E. coli compensates for the sensitivity-speed trade-off problem by operating out of equilibrium. The energy dissipation (through ATP hydrolysis) in subunits of the receptor lattice breaks the fluctuation-dissipation theorem, which allows the sensory array to have high sensitivity and high response speed at the same time. Figure 2 shows examples of speed-sensitivity trade-off curves. If the cell must meet some speed and sensitivity operational thresholds (gray shaded region) to effectively sense its environment, then there is a minimum energy input (ΔGmin) that is required. Operating at this dissipation level requires fine-tuning of the array coupling to meet both speed and sensitivity thresholds (red point). Increasing dissipation further (ΔGmin>ΔG) enhances the robustness of the signaling, opening up a range of lattice parameters (red curve) where cells can achieve both sensitive and rapid response.

Figure 2. Easing the speed-sensitivity trade-off with energy dissipation. Each curve represents the speed-sensitivity trade-off for a fixed energy cost (ΔG); changing the coupling strength in the chemosensory array moves cell signaling behavior along these curves. By increasing the energy input, the trade-off curves can be moved toward the upper right region of the plot, where both fast and sensitive response are achieved. Energy dissipation allows cells to reach the minimum operational thresholds required for survival (red dot) or open a robust range of couplings that meet these thresholds (red curve).

A structure-based modeling paradigm: Our work lays the groundwork for precise structure-based modeling of the chemosensory array and other large protein complexes. By combining details of the protein-protein interactions within these large protein complexes, unveiled by powerful experimental tools such as cryoEM, with the nonequilibrium kinetic reaction networks, we can develop quantitative models to understand and predict how protein complex structures give rise to biological functions. Our approach is highly generalizable; it will be exciting to see the range of biological complexes that can be studied within this new modeling paradigm.

Poster image credit: Adapted from A. Burt, C.K. Cassidy, P.J. Stansfeld, I, Gutsche, Alternative Architecture of the E. coli Chemosensory Array. Biomolecules 11, 495 (2021). Reproduced under Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in